Eben Parker Low

“The paniolo thanks his horse from his heart for being so smart and loyal and dependable. You think of that, waiting those few minutes on the rim. You run a hand over the pony's legs and let him know you don't want them hurt. He knows you love him. He’ll tell you so in every action and, often, by rubbing his head against your hand or shoulder. He rests against you while you stand a minute, arm thrown over his neck while you listen and study the terrain and plan your action. Sometimes the horse's muscles quiver with excitement while he stands statue-like, waiting. Your own heart is excited, beating fast. But your mind is calm, ready, and your eyes and hands and your rope.” Eben Parker Low

Eben Parker Low, also known as Rawhide Ben Low, was a famous paniolo (cowboy) on the big island of Hawaii. He was raised on Parker Ranch and later founded his own ranch - Puuwaawaa. Eben was my grandfather.

All material copyright Sam Low

Please do not copy or use text or photographs without permission. Contact me at samfilm@aol.com

A Diaspora of Memories

By Sam Low

Cattle at Parker Ranch

I am seeking my aumakua - my guardian spirits. Hawaiians believe they are the spirits of our ancestors who always acompany us through life. One family of aumakua voyaged to Hawaii in the distant past, and there they linger, inhabiting the special places where they lived and loved and perished.

This search will evenually result in a book.

The plane punches through a low layer of puffy clouds and rises over Boston Harbor. Turning west to take our course to San Francisco, I see the houses of Gloucester below the starboard wing. Further outboard, the coast swings north to Cape Ann. A long line of unbroken beach peels back upon itself where the Merrimack River breaks through to the sea. Inland, the river shoulders the land aside and broadens into Newburyport Harbor then twists as it wends westward.

I am retracing the first voyage that my great grandfather, John Somes Low, made in 1849, sailing before the mast from Boston to the gold fields of California. His father was not happy.

"Go to Lawrence engineering school at Harvard," he had told him, "and then do your traveling. You will then always have something to fall back upon. If you go you will be on your own in every way."

But John shipped aboard the brig Eagle, Captain Davis, with a cargo of lumber bound for Sacramento, then Hawaii. Across the century and a half that separates my voyage from his, I feel the blood bond tighten, then loosen, like the tide of the heart.

The great circle route from Boston to San Francisco scribes a wide arc over the planet. Beneath me, the worn adobe color of the Great Plains in Wyoming runs smack into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. The land crenellates and draws down snow. The arc takes us over Cheyenne where my grandfather Eben Parker Low brought his cowboys in 1908 and where they covered themselves in glory. An hour later, we are sliding across the junction of Utah and Nevada, not far from the "Mother Lode" mines where Eben’s father died under "mysterious circumstances."

Eben retraced his father’s steps in 1907, traveling to Schelbourne Station, Nevada to visit the mines. Schelbourne had once been a stop on the first transcontinental mail route. In 1860, Pony Express riders first crossed the Robinson Mountains from Salt Lake City and descended into a wide basin between ranges that rose up like steep rollers across a flat sea, stopping at the station for fresh mounts before proceeding on to Lake Tahoe and Sacramento. Indians once killed two stationmasters here and ran off with their ponies. The Station is today a six-room motel, a bar and a half-acre parking lot gleaming at night under a two-thousand-watt arc light. Route 93 cleaves north-south between the Wheeler and Robinson ranges. You look down the arrow straight road for ten miles in each direction and see no headlights. Above, the stars are as cold and as clear as ice. Eben caught the gold bug here and invested his retirement money to burrow even deeper than his father. He got nothing more from it than his father had.

Six hours out of Boston, we descend into the San Fernando Valley and land in San Francisco. This city is a node for many of us. Our tracks have crossed and re-crossed here.

John sailed to San Francisco around Cape Horn three times and from Hawaii twice. By 1868, when he took two of his daughters from Hawaii to Gloucester to deposit them with his parents, he could go by paddle wheel steamer from San Francisco to Panama, across the Isthmus, and then up to New York by yet another fast steamer. The trip took only about five weeks. His son, Eben, traveled a lot when he retired from ranching. He visited San Francisco in 1893, 1900, 1907 and 1932.

I imagine our paths to be a spiral of threads rising off the landscape like a gossamer dust devil so that when they cross they do not meet unless you have the imagination to tip the spiral on end and look down upon it.

Six hours after leaving San Francisco, I drive up the northern flank of Mauna Kea on the big island of Hawaii. The sun sets directly ahead of me beyond the slope of the ancient volcano. A low-pressure area has passed over the island, bringing steady winds from the north, cleaning the air. A ruby iridescent light surrounds me. The shadows are deep purple.

Against the glow, I see windbreaks of Ohia trees fanning bare limbs against the sky. Cattle stand on the tops of the small rounded hills in crisp silhouettes. Quickly it gets so dark that I lose sight of them. I am in Parker Ranch country.

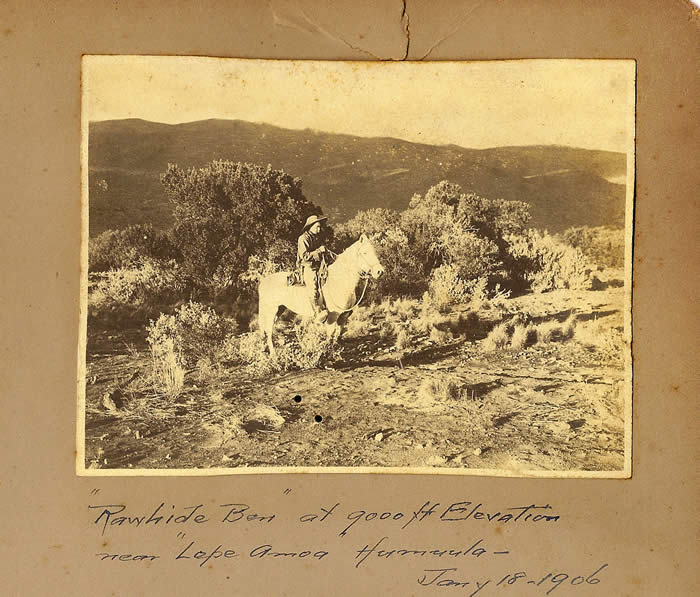

My grandfather, Eben Parker Low, was raised here in a sprawling house full of brothers and sisters. He was a cowboy known throughout the islands as "Rawhide Ben" because of his exploits as a roper of wild cattle on Mauna Kea's high flanks.

Growing up in New England with the stories my father told of my grandfather, It seemed strange to think of cowboys in Hawaii. I pictured cattle wandering among swaying palm trees. Cattle eating pineapples. Cattle in deep rainforest. Once, paging through my father’s art books, I came upon Rousseau’s “Animal Kingdom.” This, I thought, was how it must have been. Here were lions and tigers, wildebeest, giraffes, and magical griffins, all peering out from a tangle of ferns and towering trees - a Noah’s arc of animals. There were no cattle, but I imagined them there. It seemed an impossible vision.

Now I can see the vision was wrong. The land around me is like a vast tilted sea, clean of trees other than widely separated stands - windbreaks against the upland rush of air pumped by the steady trade winds. It is prairie land, like Montana or Wyoming. But it is rawer, younger. The puckering mouth of the volcano pushes through this Hawaiian prairie like a suppurating wound, drawing the land upward toward the emerging stars. According to geologists, Mauna Kea expresses forces that rise a thousand miles from the heart of the planet. This theory is recent. My grandfather had no such insight. He might have explained Mauna Kea by invoking Pele, if he bothered to explain it at all.

Eben was born beneath the Volcano’s rim and grew up on this tilting plain. He was a ranch manager and then an owner. He lost his hand in a roping accident deep in a forest on the volcano’s slopes and so he became a champion one-armed roper of cattle. In moments of depression, he mounted a horse and climbed toward the volcano’s rim until he found peace. He continued to stalk wild cattle when most men his age were content to nap on their verandahs.

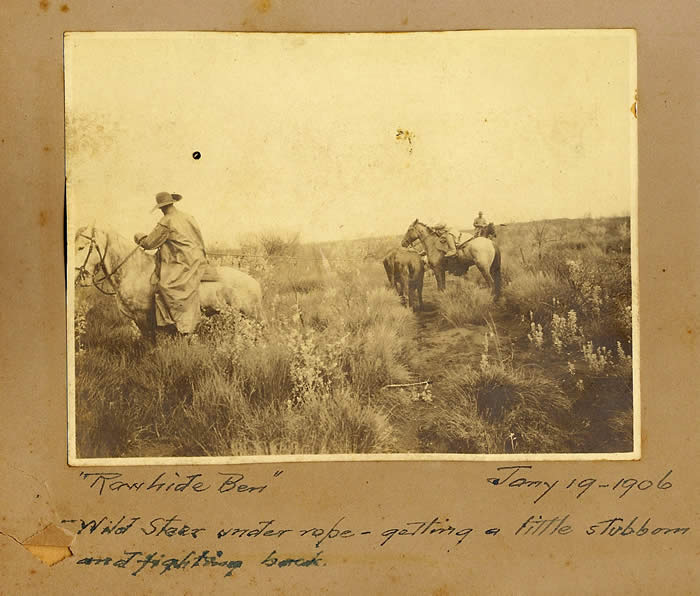

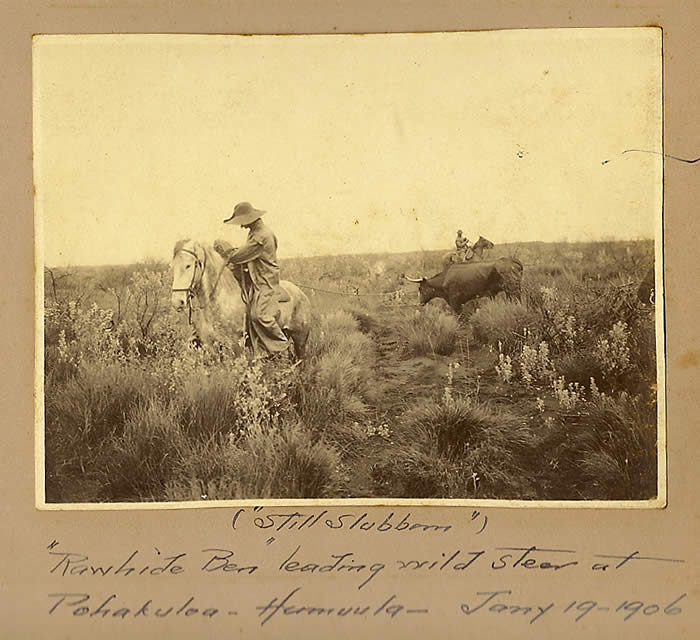

The cattle are descendents of those first brought to Hawaii by Captain George Vancouver in 1793. In Eben’s time, they had wandered unfettered for a hundred years, breeding in the uplands, feeding on moist ferns, hiding from cowboys in dense tangled underbrush. They were large and wise and dangerous. To rope them was, to say the least, extremely tricky. Of this adventure, my grandfather once wrote:

“We keep to the lee side of the cattle so they won't smell us coming. We talk and move quietly. Wild cattle like the fog – it hides them and makes heavy dew on the grass so it’s like eating and drinking at the same time. Below us a bunch are gathered in a sheltered kipuka. We rest our horses on the rim of a hill above. We cool the horses with loosened girths and a shake of the saddle and blanket. The horse sweat smells hot and strong as we lift the saddle up and it covers our man-smell. The horses watch, too, ears alert and eyes eager, waiting. Their ears pricked toward where the cattle are hidden. A moving branch or cracking twig tells us when the cattle get restless and suspicious.”

“The paniolo thanks his horse from his heart for being so smart and loyal and dependable. You think of that, waiting those few minutes on the rim. You run a hand over the pony's legs and let him know you don't want them hurt. He knew you loved him. He’d tell you so in every action and, often, by rubbing his head against your hand or shoulder. He rests against you while you stand a minute, arm thrown over his neck while you listen and study the terrain and plan your action. Sometimes the horse's muscles quiver with excitement while he stands statue-like, waiting. Your own heart is excited, beating fast. But your mind is calm, ready, and your eyes and hands and your rope.”

"All ready.”

“You hear the whispered command. You mount up and ride down over the rim.

Down, down through the swirling fog and clutching brush. No need for silence now. Just watch which way those wily cattle are going to turn. Away from you, or right at you, head and horns set for the charge. Your pony steps aside, your hand flips a loop over the horns, you take up slack and your pony is turning, watching that rope, and you're running beside the captive, then ahead of it, that beautiful Wild One. Careful. Not too close. Those horns can stab sideways.

“There’s a good tree. Get around it. You bring that head up close to the tree trunk and come in fast. Now a rope-turn around the trunk has the critter held fast, bawling, roaring, pulling and tugging to be freed. Good pony! Hold like steel while you pin those horns to the tree and take your lariat loop off. Coil the kaula, grab the rein, hop into the saddle, off for another try, and another...

“So it goes. Unless a horse is gored or falls, pinning a rider down, rider and horse struggling. Then you run in and pull the loop off that fighting critter, flap a tapadero into its face to distract him; or you grab the lariat tied to the downed rider’s pommel and drag off the critter that is charging the downed man and horse. Get that wild, fighting pipi off, any way you can! You're glad, relieved, when horse and rider are up, unhurt or maybe only slightly injured.

“If man and horse are moving, there’s a chance they will come up smiling. If not, they are dead. If the horse is bad hurt you drive your legging-knife into the spinal cord just back of his head. He kicks a couple of times, but he is out of misery. If the man is just hurt, you take him up behind you on your horse, back to the station for help. If he is dead you take him over your horse, your heart sick inside. At the station you lay him out and cover him with his yellow saddle-slicker until someone can take him home to be buried. The drive goes on. The work has to be done.

“Sometimes you dream. Someone yells your name or shakes you awake from the nightmare and you feel shame because others know you hurt inside. It's all in the day’s work. Every man on the job can be dead tomorrow. You roll over and think of how proud you will feel if you can do some brave deed and deserve the praise of the men.”

In his will, Eben asked that his ashes be spread on Mauna Kea’s flanks. And so, in 1954, a dozen riders climbed the steep slopes, gasping for breath in the thinning air. The minister was taken with altitude sickness at ten thousand feet and was left behind. At twelve thousand feet, a cardboard box was opened and from it Eben’s body was distributed to the winds.

As I drive toward Waimea, the stars appear stationary above glowing plains of cloud. But they really expand away from me, as I know from reading physics. My father’s voice lurks in memory, also expanding away. With time, the talk of all my ancestors expands away. It is a Diaspora of memories. In the trunk of my rented car is my grandfather’s voice, frozen in words he wrote many years ago. I read them, but do not understand. The words need context, place. I once imagined a simple machine that would allow me to listen to voices from the past. It was a kind of speaking tube that, inserted into the earth, would recover the talk of all the men and women who had walked there. That is why I am here.

Eben Parker Low

Brief Biography

Eben Parker Low – known in the islands as “Rawhide Ben” - was born in Honolulu on October 23, 1864, the son of John Somes Low and Martha Kekapa Fuller, the granddaughter of John Palmer Parker and his Hawaiian wife, Kipikane. He spent much of his early years on Parker Ranch.

“I was handling cows and calves by the time I was six years old,” he writes in his memoirs, “and was learning the art of busting calves and horses. I was busted up some, too, in the process of becoming the cowboy known as "Rawhide Ben.” Riding horses and roping anything with four legs seemed to be inherent in my case, as with many part-Hawaiian boys on Parker ranch. We were daring, and sometimes, perhaps, reckless, on the wide slopes of Hawaii’s broad mountains. We tackled everything from wild boars wild cattle and horses, goats and sheep... I had no education to brag about. Just plain common-sense plus some English grammar, and arithmetic and writing.”

Ben grew up on the ranch with time off for school on other islands and a stint working for Theo H. Davis. In 1890, when he was 26, he took over as manager of Pu’uhue Ranch in Kohala and began his career as one of the Big Island’s most colorful paniolo.

“The Paniolos work in the open, in God’s good sunlight and in his refreshing rains and winds. The paniolo is a free agent, a free lance depending only on God and himself to create happiness for family and friends,” Ben wrote.

“Sitting on the lanai at Puuhe,” Eben continued in his memoirs, “my mind traveled in a circle. I felt that I was wasting time and energy working for somebody else instead of accumulating something for myself and the next generation. I looked across to the wild lava flows and beyond, to the mountains and the open sky. At certain times of the day I could spy what appeared to be a green oasis in the midst of the black desolate flows.”

The oasis was a cinder cone – called Puuwaawaa - folded by deep gullies that pierced the slope of Mauna Kea. The flanks of the cone were green. Cieba and Ohia trees spilled off the cone to its base where cattle and horses grazed. In the distance, behind Puuwaawaa, Eben saw Hualalai against a stark blue sky. In the far distance, the sea shimmered under a swollen belly of cloud.

“The place kept calling to me,” Eben wrote, “I had to see it.”

Of his first visit to Puuwaawaa, Eben wrote: “As you emerge from that dense ohia forest growing in a'a lava, you cannot help but stop your horse, such a scene of beauty is spreading out before you on Puuwaawaa Hill. I never was so surprised at seeing a piece of property like that in my life. It was a perfect paradise to cast your eyes upon, especially after coming out of that dense maze of all the worst that God has created in desolation. I stood in amazement and wonderment. I couldn’t look at anything else. What a land! What a paradise! Here was a future home where I could build a ranch with the finest of everything for my family. A ranch second to none in the Hawaiian Islands. My wife stood in front of me like a dream. What a home for this beautiful woman, a place for her to bring up our children.”

Eben purchased the ranch with his partner, Robbie Hind, in 1884. Life on the ranch at Puuwaawaa was much like what Eben had experienced as a child growing up on the Parker Ranch. There was no refrigeration, also no need of it since the land provided fresh meat either on the hoof (30-30 Winchester) or on the wing (12 gauge Parker double barrel shotgun). Eben purchased coffee, rice, cloth and sugar at the store in Waimea, but little else. Most of their clothing was made at home where his wife Lizzie and the children did the sewing by hand.

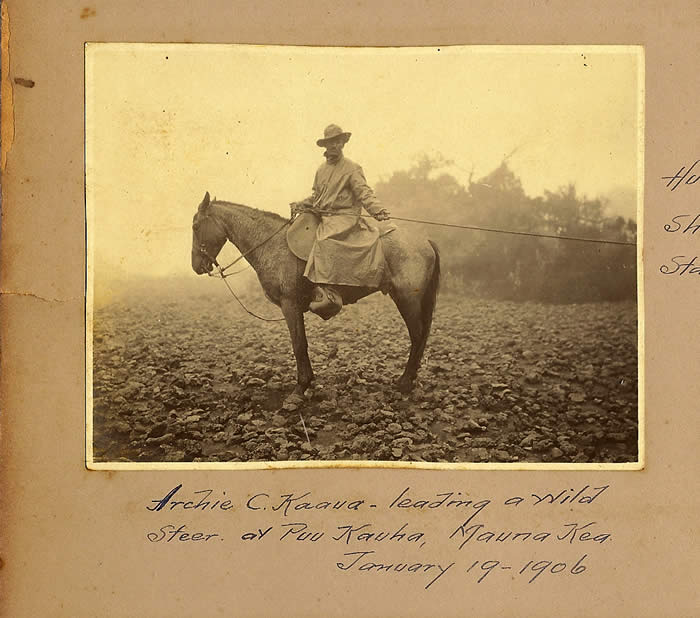

Eben managed Puuwaawaa from 1884 until 1903 when he sold his share to Robbie. In 1907 he traveled to the mainland to visit Teddy Roosevelt at the White house and went on to Cheyenne for the famous Frontier Days celebration. He appreciated the mainland cowboy’s skills but was certain that ‘his boys’ could do better. In 1908 he sent Ikua (Ikuwa) Purdy, Archie Kauua and Jack Low to compete for the world roping championship. In spite of being given mediocre horses, Ikua won the championship, Archie placed third and Jack came in sixth.

“You cannot imagine the noise of the applause our boys received from those 30,000 watchers after the announcement of the final result! The kanakas had won!,” Ben wrote of the event.

Early Memories of Parker Ranch

By Eben Parker Low

Edited by Sam Low

Captain Nichols with a Lassoed steer at Mana near Waimea, Big Island, Hawaii.

December 7th - 1888 - Eben Low caption

Young as I was in 1870 (Eben was six years old), I can well remember Robert Waipa, half brother to my mother, had charge of the milking herd, and did the milking with one helper, of 20 to 30 cows every morning, and was at the calf pen to see that each calf was ready for the mother's milking when called for by Robert blank. Never at any time was I without a small rope to rope my calf that was ornery in making the dash to the right mother, I became quite an expert in roping and rarely missed a throw, and believe it or not I worked at this game for over one year without a pair of underclothes or shoes during the cold and foggy mornings of the winter months, just blue denims. My mother with helping hands attended to the old fashioned method of making the cream from the pans and did that churning of the cream with the back breaking method of the elongated bucket churn and hand pump, and many a time I saw my mother knead bread. Did we get any pay for all of these hard back breaking manual jobs? Oh yes! The older ones, got dungaree pants and jumpers, the woman folks got calico prints, and they made their own cloths and dresses, during fogy and rainy days, and believe me there were many days like that. But not on Sundays! Oh no, that was the day of worship and meditation and was rigidly enforced. Hardly any cash was seen. The only time I really saw any cash, was on Sunday at the church where a small tribute was given.

My uncle John Parker never allowed me to ride. He was always afraid of a fall. When an occasion came to make a long trip to Waimea or to the woods for supplies or Koa bark for the tannery, Bullock wagons were used for transportation work. No horse wagons were used at that time, lighter hauling was made by pack horses and old tame steers. I never observed the eighth commandment rigidly, thou shalt not steal, when an occasion came my way and with the help of Cowboys, out of sight of the old man, I would be seen seated on an old pack horse or between the fork of a pack saddle, getting my first lesson in riding that way. What a contrast to the modern life and mode of getting a chance to learn how to ride. About 1871 I was sent to Haleakala boys school at Makawao, Maui. I learned very little but I was always interested in stock. I was at the dairy most of the time, attending to the calves and cows, and to the delivery of milk to the Moanaalu seminary. I was the sweet tow head candy kid at that time, and the big girls of the school used to run out as I came along with two other small boys with their milk. Gee! What a lot of free kisses I used to get. Carrie, and Hanah Robinson from Kona, Hawaii, were there, of course I never refused than those sweet privileges, I always considered them my relatives. John and William Johnson were were at Haleakala school at that time, Walter Jarrtt, Robert Wilcox, the first delegate from Hawaii to Washington was also there at that time. Mother Thurston was our matron. Lorrin A. Thurton was also there at that time. And also many others who were prominent in the history of Hawaii received their early education from this institution and under the leadership of Clark the head principal of the school.

I cannot go along with this biography of my life without touching on a few lines in memory of mother Thurston. I called her mother because she certainly acted like my mother, I was to her as her own child, the motherly love and kindly treatment I received at her hands at Haleakala is so embedded in my memory, the only time it will be forgotten and that will be after I pass on from this mortal life. No love or care was given me by my own mother or from the Parker's that can compare with her love and devotion to that little tow headed lad at Haleakala school. That devotion and love never left her loving soul until she departed this life in Honolulu. She was always asking about me. And there was never a time during my existence that I failed to call and hear that soft and motherly voice of hers. I came back from Haleakala school about the latter part of a 1872 and stayed at Puuopelu with my uncle John Parker.

Group of riders at Mana

December 7th - 1888 - Eben Low caption

Parker II engaged a man by the name of William Cuthbert, an English man with the title of Earl of Canbury, one of those young lords of the British country ho had lost everything to his trusted bookkeeper and Secretary, and Cuthbert became a part of the family and actually was the guiding light of everything which went on. That was about 1875, and from that date on he was that trusted man and he certainly was a fine gentleman. He passed on after a short illness in the hospital in Honolulu in a 1898.

Lihue was the business headquarters of the Waimea grazing and agricultural company, composing the office, store, boiling house, quarters for the men, corrals for the animals, and all the rest. This ceased after the purchase when headquarters were moved to Mana and Puuopelu. The boiling house was dismantled and taken over to Puuopelu and placed in charge of Charles Williams who carried on the tallow and hide business of the Parker ranch until about 1882.

Kahoohanohano, brother of John Parker's wife, Hanai, was made foreman of the ranch. All catrtle drives, roundup for branding, or cattle for slaughter, for hides and tallow, and shipments to Molokai and Honolulu, were under his full control. His knowledge of cattle and their haunts and the handling of man who worked with him was wonderful. Waimea at that time was far from peaceful, a good many arrests were made but few who were imprisoned in that hot cattle town. Many were caught red handed, but jury trials, especially at Waimea where court trials were held, were not too successful because jurors never agreed and invariably they returned a verdict of not guilty. So Waima was the hot hell town in comparison to some of the United States towns of the West or their wild and wollie West celebrities.

Parker Ranch Roundups

By Eben Parker Low

Edited by Sam Low

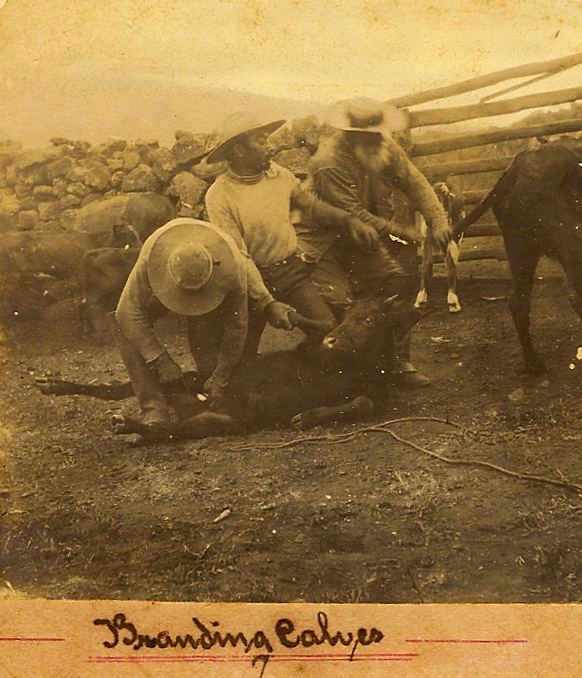

Doesn't look like branding to me (Sam Low)

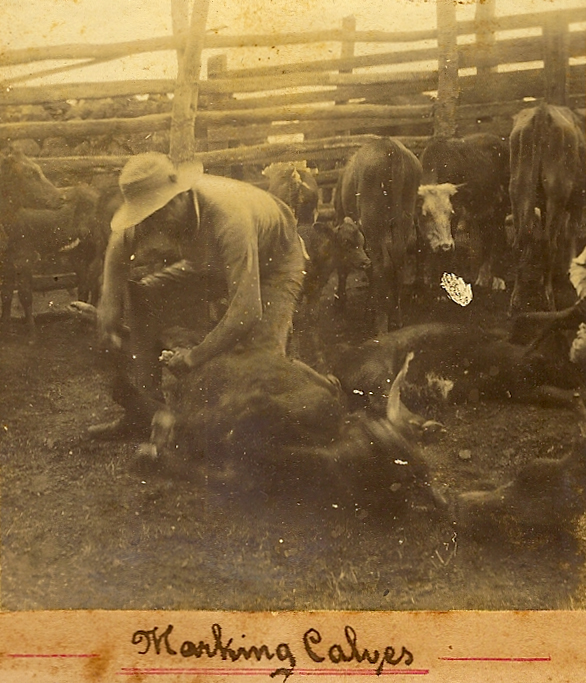

Such grand days, those early experiences of seeing the handling of thousands of cattle. The whole general roundup of driving, pen work, cutting out animals for branding, or for breeding, or for market, was run by men who knew their job well and loved it. Please remember that these Hawaiian cowboys were of the highest caliber, and I pay tribute to them as some of the finest in that profession. They were real he-men, born and raised with horses and cattle from their childhood, and ranching and its work and play was their whole lie. They knew nothing else, for many of them could not even write their names, but let them see a horse, a saddle, a good rawhide rope and bridal, and they were happy. Everything beyond that was secondary. I recall vividly, in the years 1878, 1879 and 1880, I went back to Hawaii for my summer vacation, I was allowed an old plug of a horse and as a companion and teacher I had Kirchoff who was called Makika because of his diminutive size, but he was a lively and an excellent horse men. He had charge of horses being broken to harness and cart work and my uncle John (Parker) placed me under him because he was a careful man. The slow men were always behind the great herds of cattle in a general roundup, and that was where I was kept, too, although I did not mean to say that Kirchoff was a slow man by any means. He was real lightning in action as were most of those man, but he had me to teach. The best men were always in the lead and along each side of the herd, they were mounted on fine fast horses to guard and keep the herd intact.

Starting for a cattle drive - Eben Low caption

Stampedes a Danger

The wild unbranded cattle would always try to break away from the herd and start a stampede, and so careful watch had to be kept over them all, and the man did not stay too close to the general herd, thus giving it plenty of room to move along comfortably like a steady, slow stream going straight to the big pens. The branding pens were up back of the Mana home, and there was an uphill pull of about six miles to get to them, hence they must not be hurried. Many and many a time, wild four and five-year-old unbranded bulls would break from that moving heard and try to get back to their dense forest home, and then was the time to see those vigilant cowboys go into whirlwind action! Then was the time to see those rear herd riders, those A-1 cowboys who were the rear guard, do their stuff to drive the bad wild ones back into their herd, or to rope them and take them back into it. Sometimes a bunch of thirty to sixty, or more, would try to get away, but they were always brought back in control. When a bull begins to fight, and insists on getting away, a halt is called, and slowly the stream of cattle comes to stop and it is rested for a breathing spell. After the herd gets through milling and quiets down the small calves would drop to the rear and begin bawling for their mothers, and worried mothers bellowed for their keiki and began trying to find them.

The man move out, allowing more room but keeping watch for any breaks and the cowboys who have gone after the runaways are galloping after them, bringing them back or roping them in, and it is breathtaking to watch those fleeing cattle and those wise, fast cow ponies and the expert riders after them. The speed, the unison of horse and rider, the skill, the quickness of hand and eye and the fast turns, and sure footedness of those ponies. Perhaps a blowing, frothy mouthed bull will turn to fight. His eyes gleam red and wickedly and threatening bellows issue from his throat and his huge chest, and he paws the earth in rage while he challenges. A man and horse must know how do accept that challenge, or it means injury or death to them. Their wits are pitted against those of the wise bull and watchers can get a real thrill.

After all this is settled, the rest gratefully taken, saddles cinched up, and maybe a cigarette enjoyed by those men who smoke, the foreman gives a sign and then rides on, and slowly the herd begins to move out, following the lead man and being controlled by them, the side riders and the rear guard.

By late afternoon the herds are corralled or are in their home paddock where they rest that night although the bawling keeps up until all mothers and calves are settled down and the bulls decide to stop pacing and keeping watch for freedom.

Then, that enormous herd of wild, semi-wild and tame cattle are forced into a large and strongly built stone walled paddock with heavy gates. The gates are bars stoutly bound with manila ropes, and can withstand a great deal of heavy pressure from the shoving, milling stock.

The riders go to the horse corrals and get their roping horses sorted out and placed in the smaller corrals for branding work next day.

As Many as Two Hundred Men

I've seen as many as two hundred men taking part in the big Parker Ranch drives. There are many others who are just on-lookers and do not participate beyond riding along behind the drive or sitting atop the corral to watch the show when the branding begins. Only expert riders and ropers control the handling efficiently and tenderfeet would only be in the way, or actually a danger to the cowboys themselves. Not only men and horses are carefully selected, but also the men handling the throwing of calves and tending the fires and the branding irons. The branding men must be strong, fast and bright to know their business of burning just right; of returning to their grease tank and calling out loudly in Hawaiian “kane” for the males, “wahine” for the females, and the tally man writes down the number of animals branded. The tallyman has no time to talk, and must keep the books properly so there is no mistake. If he is bothered by questions he is liable to use the cowboy’s vocabulary of “shut up God Damn you!” And mean it!

Two or three man keep the fires going and well provided with wood, and several others must be expert in castrating and ear marking, for this last is a job requiring skill and precision.

The Really Dangerous Work

The Really Dangerous Work

After thousands of calves are branded, the foreman calls for lunch, and when the men have eaten the riders get fresh horses and the really dangerous work begins. The men at the fires are cautious of the danger and are always ready to scale the stone wall if anything happens. Large unbranded bulls and cows are bought to the branding pens, are roped and dragged to the fires, are bull-dogged by the men, or hind footed and stretched out by the riders, then branded and worked upon as necessary and then released, but only after the sharp tips of the horns are sawed off about three inches to prevent any perilous harm to horses and man from goring.

I have traveled a lot during my life, but have never seen greater deeds of courage and strength and marvelous endurance and performance by cowboys on duty as I have seen at Parker Ranch. These Hawaiian cowboys do their duties as if it were pleasure rather than hard, dangerous work. They are always smiling or laughing and ready with timely wit for anything happening. They were real men every one of them, and I want the reader to understand that everything written is not just a fancy imagination or thought of mine in making this story like a romance and fiction for the sake of the sale to make something out of. Oh No! It is to show the true life of the Hawaiian cowboy, or man if you please, as the years go on by, to the world over, for his lovable nature, behavior, hospitality and his true devotion to his employer. Please remember, I am quoting from direct contact and knowledge of them for I was raised like one of them, so I write and speak in terms of the exact nature of the race in my time. I cannot compare the cowboys of this age to what they were fifty or sixty years ago. Time has changed the environment and the life of everything and it is difficult to write these lines and believe that I am stating the exact and unadulterated facts. The difference to me is like cheese and chalk to compare the past to the present.

The general roundup on the Parker Ranch in the early days of my life, from 1875 to the time I took charge of Puuhue ranch in 1890 as manager, was the same in all of its details; roping, handling of the unbranded stock, castrating, and ear marking, branding until 1893 when I and my brother-in-law Robbie Hind went into the cattle business, on the land of Puuwaawaa as Hind and Low.

Waimea Hawaii

the early days

Hell Town – Waimea, Hawaii

By Eben Parker Low

Edited by Sam Low

Rawhide Ben was known for his practical jokes – the following is an excerpt from his written stories.

Waimea at that time (late eighteen hundreds) was far from peaceful. A good many arrests were made but few were imprisoned in that hot cattle town. Even though many were caught red handed the jury trials, especially at Waimea where court trials were held, were not too successful because jurors never agreed and invariably they returned a verdict of not guilty. During times when court was in session, Waimea was particularly noted for its halcyon days, for all the horse and cattle thieves and the bad man who had been released for lack of evidence would collect and watch those who were held. So Waimea was a hot hell town in comparison to some of the mainland towns of the West.

Guilty or not? It depends on the quality of the okolehao

One case I know of, having been an eyewitness at the trial in question, was during the eighties when I was on vacation from Honolulu. It was a case of okolehao distilling where the man was caught in the act with all his utensils, ingredients of ti roots, and the bottled liquor. Now, liquor of every description was allowed in from abroad by the laws of the islands, but the home product of okolehao was banned.

The judge for this particular trial was one from the Supreme Court of Honolulu who came once a year under the monarchy, to hold sway and mete out justice to the offenders, but things go hey-wire at times and this was one of those times. The okolehao case came up and under the advice of his lawyer the man pleaded not guilty. The prosecution put up a fine case while the defendant put up a sad case and pleaded for mercy because he knew that the jury were Britishers from Kohala who were fond of good liquor and particularly of good okolehao. The jury, after being released to their private room for deliberation of the case, soon knocked at the door for the Bailiff who thought they were ready with their verdict. He notified the judge, the spectators crowded back into the courtroom, and they were all astounded to find that all the jury wanted was to sample the okolehao, for they declared that actually no one knew whether the bottles contained liquor or not. A short time later, another bottle was called for in order to study the case further, and then another. Finally the jury returned with their verdict and staggered everyone, even the accused, with not guilty.

Later, one of the jury was asked how come? The answer was, “any man who can manufacture good stuff like that is not guilty of a misdemeanor, but if it had been bad stuff he would've gotten the works.” There was justice in a Hawaiian cow town.

Deputy Bright Gets his Comeuppance

The deputy sheriff was a cocky half-caste by the name of Jim Bright. He weighed about ninety pounds and stood about five-feet-two inches but was as cocky as a fighting bantam. And he was so proud of his position that he thought he was all hell in his ability. He notified the chief justice, who was a man filled with religious scruples, that he had completely put the town in order and had rid it of drunkenness and that all riotous disturbances were at an end. The chief justice complemented him for his ability in performing this marvelous feat and, whether the justice actually believed it or not, he gave that impression and it was sufficient to bolster the sheriff’s ego to the skies.

The news spread like wild fire to every part of that town and by midnight a drunken hilarity was reigning there. The organized gang of the town was of good and bad, and, strange to say, the leader of it was the youngest man, the captain of the cowhands and a grandson of the founder of the great Parker Ranch! From the corner of the Frank Johnson lot, to Koki’s store almost a half-mile away, banana trees miraculously grew up that whole distance between midnight and morning. Some of the trees already had full grown bunches of bananas and the whole row of trees had sprouted directly in the middle of the road! At the top of the road, at the end of the row of trees, stood the hale which formerly had been the privy for the schoolhouse. It stood in full view of the town with a tall pole waving an all-white flag with the name Coffee Shop painted in bold letters on the flag. The poor sheriff took one look that early morning and he realized that the offending trees and privy obstructing the road could not be removed before the chief justice arrived.

Every effort was made to locate the offenders who played the prank but to no avail. Many of those who had participated were well known but no man dared reveal their names so the matter died a natural death and went by the board as one of that hell town’s ordinary celebrations.

A Black Something with Huge Shining Eyes

On another occasion, a wild bull-calf was tied to the bell rope of the first mission church of Waimea at about three AM on a Sunday morning. Lyons, one of the missionaries from the fifth installation to Hawaii, had been sent there to Christianize the pagan Hawaiians into the Palace of Righteousness. But he had run into a veritable hornets nest, and had, I believe, the hardest place in the islands because we had there a wild, mixed population of every nationality - Americans, Mexicans, Spanish, Hawaiians, Irish, and others. The majority of the higher brackets were English and Irish, and of course there were the carefree, loving Hawaiians who were easily swayed into a wild way of life by any wild whites or Mexicans. When Lyons sent his Deacon, a dignified Hawaiian named Mahuka who weighed nearly three hundred and sixty pounds, most of it in his opu (stomach), to investigate the cause of the commotion at the church so early in the morning, poor Mahuka was catapulted by this infuriated bull calf. He was so shaken, so stupefied by the apparition of a “black something with huge shining eyes,” that he hastened back to Lyons with the news that the devil was within the churchyard. With the coming of daylight, the bull calf was found, removed, and the bell tolled for the faithful. There was no end of merriment over the affair, investigation was to no avail, and it eventually receded into history as one of the ordinary circuses staged in that cowboy town.

Paniolo still rope and brand cattle on the Big Island as they did a century or more ago...

Lost Left Hand at Hopuwai

By Eben Parker Low

Edited by Sam Low

Photos: Eben Low scrapbook

The following is a story, written by my grandfather, about the incident in which he lost his hand while roping wild cattle on the slopes of Mauna Kea on the Big Island.

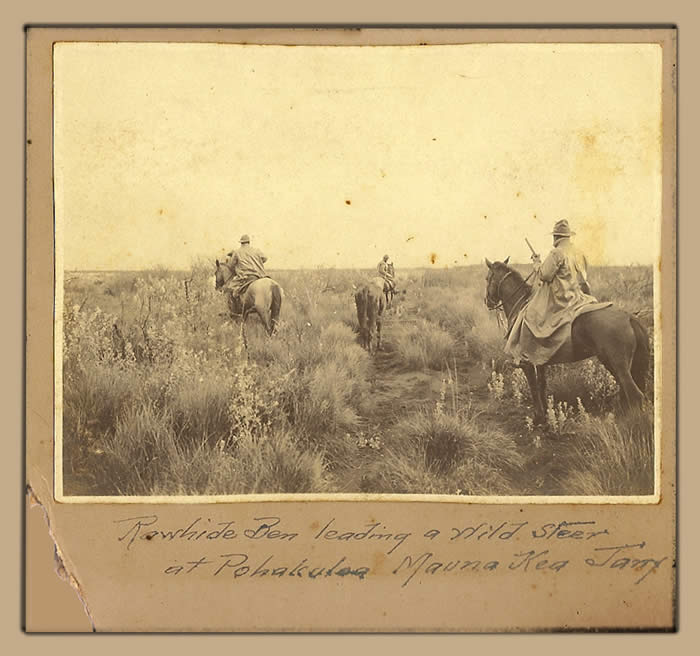

In May of 1892, I left Pu'u Hue Ranch with 30 head of Pin Steers, 25 head of the finest roping horses in the Hawaiian Islands and 9 men including myself to rope wild cattle on land under the control of the Humu'ula Sheep Station. We were under contract for $7.00 per head with Mr. August Hannenberg, manager of the station at Humu'ula, payment to be made for every head standing at the time of delivery. We had a contingent of the very finest ropers that ever grouped together for this kind of work. Every man was a professional and an expert, for this dangerous work requires young fearless men with years of experience. Every man knew that and was prepared to take the consequences, and consequences there were as you will soon see.

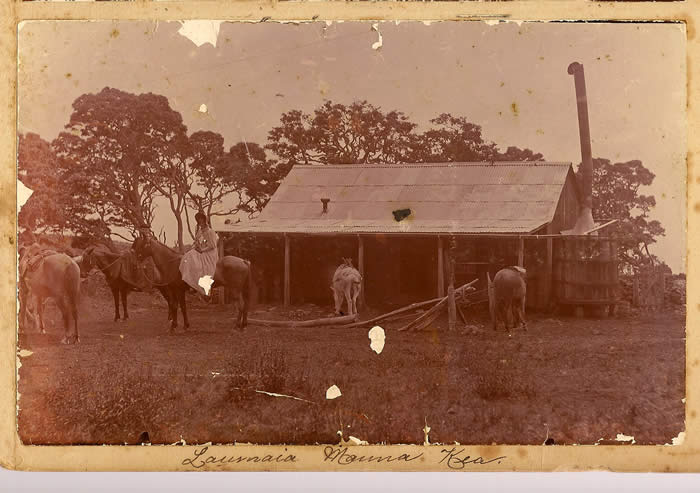

We got a few head of cows and bulls before we arrived at Humu'ula, in the Southwestern forest of Mamane trees at Pohakuloa. After a day's rest we continued on to the North Side of Mauna Kea, facing the Hamakua and Hilo Coast. The road after leaving the station was nothing but trail leading from Humu'ula to Laumai'a, passing Pu'u Oo Ranch, now under a long lease to William H. Shipman. At that time, 1892, the Koa Forest was so thick with Aea, Mamane, Naio (Bastard Sandal Wood), Kolea, Opiko, high Amau and Pulu ferns and a spattering of Rapala Kepau and Papala lei trees, and the trail so muddy, that we were obliged to go nearly single file all that distance which made traveling dangerous and slow. To see that country at this writing, in 1941, you cannot believe that it is the same road in the same country. The forest with its enormous underbush has disappeared to fully 3 to 5 miles from the higher elevation line to the now existing forest. The only reminder is just a few of the enormous and stately Koa trees in a decayed and dying state, trees which took ages to grow. The country that was once blessed with trees and vegetation is now gulches, hills and empty pools of water all bleak and bare. It almost seems sacrilegious to say that it has all been denuded by the ravages of wild cattle and hogs and by thousands of sheep during the last 75 years.

After we got fairly settled at Laumai'a, I rode out to do some scouting to find out exactly the best way to work without disturbing the cattle in their stamping grounds. If they run into the lower edge of the scant forest which adjoins the dense pulu ferns, where it is boggy, they become hard to catch. Even if we did manage to catch any in all that mud we would just have to kill them and take the hides. Cattle caught in that kind of country never survive a long drive so we leave them alone. We caught a few large young bulls, some cows and heifers, but paid for them with some minor spills because of pits, ditches and logs hidden in the ferns.

We kept our finest horses for the upper sections of the forest where there is good dry terrain and fine sound flats - a regular stamping ground at about 10,000 feet of elevation. We reserved this particular section of the mountain for the real catch, knowing that herds of unbranded steers roam there. We all came home early and had some real good rest and saw to it that our work horses for the next day had a good feed of oats and fine green hay. Our roping horses were all selected from the string and tethered out under rope during the night and we all retired early.

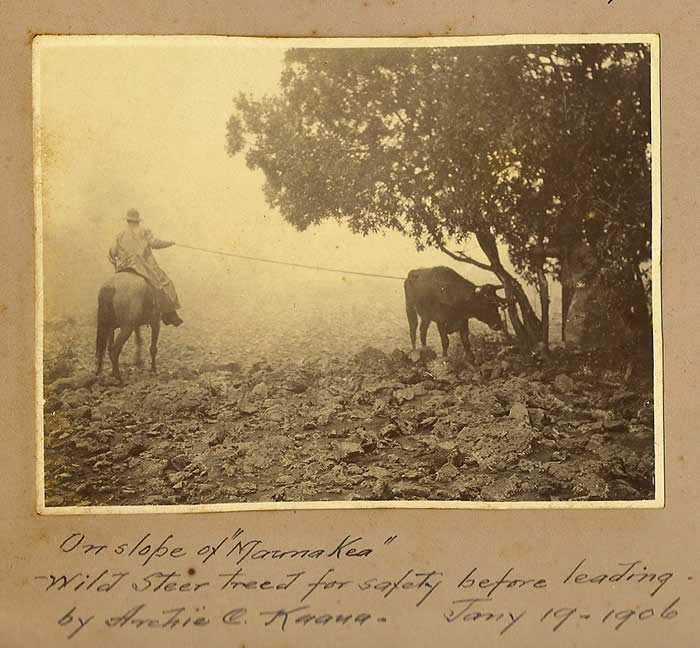

"Humuula Cowboys in slickers on slope of Mauna Kea roping wild cattle"

January 19, 1906

Rawhide Ben second from left

Archie Kaaua far right

At 3 A.M., all hands were called to coffee and all responded except my brother Jack who turned up last and begged to be excused from roping that morning. He said that he would come along with the pin herd and be the "cheap hand man." He told us that he didn't want to come because of a dream he had that night. It was exactly the same dream that he had twice before. He refused to discuss the details but said that if he came along with us that we would bring back his dead body. It was to no avail to try and get him to change his mind. He was that set. I had to give in and allow him to follow us up with 20 head of tame pin oxen later in the day. Jack was a wonderful lad, fearless and fast, and absolutely sure with his throw. If any animal gets in his way, you can count on Jack to get him. But he had a cowboy superstition and the only way to keep him happy was to appease him when the horror and fear got on him. I let him have his way.

All the others were happy and ready for the fray. They were a string of the best men. I would pit them against the finest in the world and wager my silver spurs and $2000.00 saddle against anyone in a contest with them, whether on mountains or plains. Later, when I sent three of my boys to the 1908 Frontier Days in Cheyenne, Wyoming to compete in the roping contest for the World Champion Roping title, they proved I was right.

Ikua Purdy, Archie Kaaua and I led the van on that early morning, followed closely by three other great and brilliant ropers, Sam Kahalekui, John Lanakila and Robert Steven and a young lad whose name I cannot recall. We rode along like mutes, no talking was allowed and the bells to our spurs were all tied and muffled as we wended our way on that trail of jangled ferns at the upper limit of the forest. It was a beautiful clear morning, cold and crisp, with a few stars still visible above. The wind was cold (Kehau) and frosty off the mountain and favorable to us as we rode up to the stamping grounds. Whatever cattle that were returning from the mountain on the way down slope to their safety zone would be coming with the wind against any noise or scent of us. We were in dense jungle and forest, just fine.

We heard the bulls bellowing softly as they came slowly downslope. I told the boys that we had just enough time to get off the trail and into the clear. There were very few clear spots, but anything was better than meeting the on-coming cattle on that one-horse trail. Large logs lying hidden in the ferns and holes where wild sows and boars burrow for fern roots made this treacherous ground. You never know when your horse might step on a boar in slumber or a sow and her brood, hidden in the undergrowth, and then what a row of squeals and snorting of horses and cursing of men and perhaps the thud of falling horse and rider. After we got out of the ferns, and out into a small opening with some good chance of roping those wild animals, we dismounted, readjusted saddles and let the girth slack for a while. We waited in silence with our lariats ready, well under cover of tall trees and fallen logs. We did not have to stand in silence for long. Three large big black bulls appeared, all of them close to each other. We cinched up our saddles, got our rawhide riatas ready and were off like hawks. Each of us knew which bull to go for so that we wouldn't get mixed up by trying to get the same one. I waved at the other men to stop as they were quite in the rear. They knew what that meant. They got ready in case one of us missed or needed help.

When the bulls got close enough for roping, I gave the order and we were off in a flash. Suddenly, the largest bull veered off and I was right on top of him, ready to make a short quick throw. Just then, my horse stepped into a hog hole and down I went. I was thrown badly but not injured. Ikua Purdy and Archie Kaaua got their bulls and one of the boys in the rear got the one I was after. I congratulated the boys for their fast and brilliant work.

From that time on, the work progressed nicely. Afterward, I felt that we should have let those few head of wild ones go and have concentrated on cattle out in the open at higher altitude with a better chance for getting larger bulls, steers and fat cows. But the temptation was too great to let go a chance like that. Our luck to this time was fine. We tied all the animals we caught securely to trees and we killed a young heifer for meat for the day and for our headquarters camp at Laumai'a. There was a large stone-walled paddock of about five acres in good order at Luamaia and there we pitched our tents and rested our hoses and ourselves. We waited for the arrival of the pin oxen and our reserve mounts and supplies.

We usually led the cattle roped at the higher elevations down to the lower elevation as that was easier and saved a lot of time compared to driving the slow Pin oxen up. But leading them was a dangerous affair in that part of the uplands where the forest was thick and the going uncertain. This is where I met with the accident that nearly cost me my life. After I was well, my brother Jack told me he knew that someone in our family was going to be injured or killed and that was why he refused to do any dangerous work on that day, little thinking I was to be the victim. It really was a peculiar and almost unbelievable story to tell. And the way it ended....

That day we got a total of thirteen head of cattle. Everything seemed to point to danger, even that unlucky number, although at the time it did not occur to me. I had always laughed at superstitions like that. At the time I was only twenty-eight years old, married and with one daughter and a baby on the way. I was full of ambition for my dear ones, and full of joyous enthusiasm for my work and future with a fine family. Accidents and death might come to others, but not to me.

In the future, when anyone asks me how I lost my arm, I'll tell them to read the book. I shrink with horror in feeling how near death I was without having to tell and retell the story of the accident.

All the cattle we caught were carefully coupled to pin oxen with brand new three-inch manilla rope. Not a single one was injured during the entire operation. They were not released until after the third or fourth day, with two men to prevent them going astray. Every day the pinned cattle and their coupled victims were allowed to drink from nearby water holes and to graze until about four thirty P.M. Then they were driven back into the large stone corral for safety during the night. The gates were securely fastened with heavy rope for extra security. This goes on, day in and day out, until the herd is large enough for a safe return home. It is really remarkable how a herd of the wildest cattle are cowed and tamed after just a few days of this sort of easy handling. They never try to escape or stray more than fifteen feet from the tame pin oxen. They never try to break away or stampede. The herders kept constant watch, of course, just in case. Its not so much that the wild ones will break away, but the tame oxen are always trying to stray from the herding grounds.

There was one large unbranded cow which had been roped on the flat of Waiki'i and tied to a Mamane tree by Sam Kahalekui, one of the best men in the string. I sent him back to lead this wild cow down to the flat where the others were with the pin animals. I allowed Robert Steven and my brother Archie to go up and help Sam. One man would have been sufficient, but I knew the very moment the cow thinks she's got her freedom, and sees that man only a few feet ahead of her... I leave it up to the reader's imagination. If you were a cow, what would you do? One extra man would have been sufficient for the job. There was no necessity of sending a third man and there was no sense of me going. Above all, I had saddled my most powerful horse, and he was fast but he had a brute of a mouth and was hard to control even with a severe Spanish spade bit - a very dangerous animal to use for that kind of work. Such is fate!

The very moment the last turn of the rope was free from that animal's head, she was off like a flash of lightening for that man ahead of her. Sam knew what it meant if he did not keep clear of those needle pointed horns. At the same time, he had to coil the slack of his lariat faster than a fisherman hauls in his line with a reel. But that cow was faster than Sam's hand in that fifty yard dash. She stepped into the slack of the rope and when the jerk came she was thrown so hard that I thought her ribs were fractured to atoms. That gave Sam time free the cow from that tangle and to gather up the loose coil and wait for the cow's reaction. She was up and again after her man. Now we were following at a fast clip. I yelled to Sam to be careful with the rope and keep it clear of the cow and watch both her and the trees closely because she might suddenly veer to the right or left. But before that happened she did a trick she had done before, got her front legs caught in the rope and this time was thrown so hard she lay stunned for a moment. I was off my horse and held her down and gave Sam a Hell of a calling down for that crass piece of work.

We were then into the thickest part of the Mamane and Naio forest at about 8000 feet of elevation. I told Sam that it was impossible to go any further with that animal in that way. I asked Archie to get off and hold the animal down while I adjusted my saddle, blanket and girth, and made sure that everything was Okay. I told Robert Steven to take the lead and give me the right road guide down through the dense forest, to prevent any further falls or accidents. I was very anxious to get that large and fine cow down to Kohala.

Everything was ready. The cow jumped to her feet and came at me like a wild mountain lion in a charge. I thought that last fall would have slowed her down. Not by a damn sight! She was charging right at me. My lariat was in my right hand with the reins. I started coiling the rope faster than you can wink and started checking the speed of that hard-mouthed horse, too. I allowed that cow to get within about three feet of my running horse, keeping everything under control. The slack of rope was quickly coiled up and snugly placed into my right hand, my left hand on the rope behind the cantle of the saddle in tight control. Everything was going like clockwork. I kept my eyes wide open to front and rear and kept that cow closely behind me, almost within poking distance of my horse. My idea was to keep her mind on me all of the time by keeping her in close formation til we got through that forest to the open country below. In that way, we went sailing down the mountain side at good speed and in close formation. I was still leading her on my left side. We were just approaching three stout Mamane trees on my right, and going like blue hell, when suddenly, for no reason that I know of, that damned cow gave up that close chase and shot off to the right of the first tree. I called out, "Look out, look out something is going to happen." "Believe it or not" Ripley, with all of his curious tales, will have to check this one out for fast thinking and action. One end of the rope was solidly around that 900 pound animal's horns, the other tied solidly to the horn of my saddle and, going at racing speed, the rest of the rope was encircling that stout tree with me on one side and the racing cow on the other. The worst part of it was that I had the rope on my left side. It meant that when we came to the end of the slack that I might be cut in half. Quick action was necessary to get that rope from the left to the right side to avoid serious calamity or death. I knew something was going to happen anyway and all I could hope to do was try to avoid anything worse than a fall.

I quickly threw the rope over my head from the left to the right side to prevent the rope cutting me in half. I adjusted my right hand to the rope. My left hand went to the reins and I started hauling on the bridle to ease up the speed of that hard bitted horse, slacking up the balance of the coil of that rope at the same time. I was laying back with my full strength on that bridle and let my hand, unbeknown, get so close to the pommel that when the rope tightened up it caught my wrist and forced it to the side of the pommel. A few inches more and the rope would have knocked my hand clear, but instead of that it forced it to the pommel of my saddle and cut my hand half off across my wrist. Imagine the impact and force I received when the full slack of rope ended around that tree with me on one side and the cow on the other! It looked like the cow was undertaking a triple somersault on the other end of that stout bullhide lariat which snapped like a piece of thread! I felt the shock as if I was struck by lightening. Looking down I saw the blood gushing from my hand and lacerated arm. The boys were immediately at my side and rendered all assistance possible by checking the flow of blood with a tourniquet knot. I was then in a severe predicament - a hundred miles from any telephone or medicine, and practically in no-man's land as far as any assistance was concerned. The boys wanted to pack me to Hopuwai Camp, one of the sheep station's quarters. I said that I could walk and did walk the whole way to the camp, a distance of about five or six miles, with my injured hand held up by my good one all the way.

Ikua Purdy was immediately on his way on horseback to Honokoa to get Dr. Greenfield, taking the shortest cut through the forest and though Horner's Ranch. It was fortunate that he knew that part of the terrain which made his traveling easy and fast. Thirty-five miles in that country on horseback is some tough traveling. When he reached Honokoa, Dr. Greenfield was not available, having an unexpected maternity case. The next nearest doctor was a Japanese doctor seven miles away at Kukuihaele. He reached that doctor and the two came up on horseback clear up to Hopuwai at about 6000 feet of elevation, a distance of about forty-five miles. They reached camp about four o'clock in the morning and the doctor immediately attended to my hand which was in pretty bad shape by that time. Gangrene had set in and every minute was precious to get me to Mana, the nearest and best location for first aid treatment, and that was thirty-five miles away. The pain was intense and I suffered the whole day until the arrival of the doctor that morning. I could not take any nourishment until the agony was eased by some medicine that the doctor gave me. I had lost a good deal of blood, but was still strong and eager to push on to Mana.

Mr. John Maguire at Kahua was telephoned to get Dr. Weddick, one of the greatest surgeons in the country, and bring him immediately to Mana, drunk or sober. The message was sent by Ikua Purdy from Honokaa. Maguire got busy and located Weddick who was drunk as a boiled owl when they reached him at his home in Kohala. They gathered together all his kit of tools and anything he had that looked like surgical instruments, and took no chances of leaving a single thing behind. They picked up the drunken doctor and threw him into the buckboard, and the span of horses with their load was on their way to Mana, a distance of about 35 miles. My wife was notified at Pu'u Hue and she too came speeding on her way to me. Everyone was in a cyclone of excitement and moving fast to reach Mana, the old original home of my grandfather, J.P. Parker. About half-way across the Kohala mountains, the old doctor got partly out of his stupor and wanted to know what in the Hell they were trying to do to him and where they were taking him to. When he was told and understood that he was going to aid his bosom friend, Eben Low, whose life was hanging in the balance, they could not go fast enough for him. He sobered up double quick and he and my wife reached us at about the same time.

After he treated my lacerated and gangrened hand and had it properly bandaged, he gave me some stimulant to stand the ordeal of that hard ride. I tried to eat but could not. I mounted and we started off. We passed Keanakolu and Kaimikoa Ranch and on to the boundary of the Parker Homer Ranch at Hanaipoe right on the land which my father had once owned and now was one of the Parker Ranch stations on the mountain, a distance of about 20 miles from Hopuwai. The stationkeeper at Keanakolu was Ione, the old Hawaiian who for years was one of my best pals and guide, and also one of Shipman's trusted men. The girls from Mana, Helen Parker who later married Carl Widemann, Mollie Randall who later became Palmer Hood's wife, and a few others, met us at Hanaipoe.

At that point I felt for the first time like fainting, so I got down off my horse and walked over to a Kolea tree and sat down and leaned against its trunk in a weak and dazed condition. The girls attended to me and I asked for a poi cocktail, thinking that since I had arrived at the station there might be some poi. My brother Jack went up to Ione and got a mixture of milk and poi and I took it down. It tasted like Manna from heaven. It revived me wonderfully and in about fifteen minutes we were off again. We arrived at Mana late in the afternoon.

When Dr. Weddick arrived, he did not lose any time in getting busy. He certainly knew his business. I thank God he was the one chosen to operate on my hand. He said to my brother and to everyone in hearing that it was too late to save the hand, an operation was the only course to take. The gangrene had got beyond the stage of safety and he must try to save my life. But he could not operate on me that evening and would have to wait until morning. Knowing its full meaning, I was prepared to go through with it and take the shock like a true soldier. But my brother broke down and wept like a child and said to the doctor, "I would rather you cut my arm than my brother's - to see him in this world with one hand, when he has a wife and family to support!" Then he ran out of the room.

Next morning, in one of the ranch bedrooms at Mana, I was operated on with every faith in that skilled surgeon whom I thank God for. We were not in a hospital surrounded with extra doctors, nurses clad in white with their gauze muzzles on their noses and mouths, no gloves and all kinds of shindigs to ward off infection. I thought only of my outdoor life and handling thousands of calves, old and young bulls, with not an ounce of anesthesia used, all within a thousand yards of that very room where I would go through with my own operation. An uneducated man was standing by that doctor as his helper, just a plain everyday blacksmith who tended to the hot water with a tin pan and a bucket from the kitchen. He was a good horseshoer and a fairly good wheelwright. Pretty and intelligent Mollie Randall, who was visiting the Parkers at that time, volunteered as nurse and aided during the more serious part of the operation in seeing that the bandages and various implements were at the doctor's hand so he would not have to waste time looking for them during the operation. Crude as it may have looked, to me that doctor was a marvel. I was under anesthesia when the doctor operated on me, but he later told me about the intelligence and devoted attendance of all those who volunteered during the operation.

My wife was not allowed in the room by the doctor neither during the operation nor the days after while I recuperated because of her delicate condition. That doctor attended to changing the dressings and cleaning the wound during the whole time that I was at Mana. It was about three weeks, during which he gave me opiates to relieve the intense pain. He admitted to me, afterward, that he was afraid I might become addicted through so much use of the drug.

For ten days, Dr. Weddick never left my room except for meals. He told me after the tenth day that he could not say for sure which way it was going to go, for better or worse. He told me that except for the fact that I neither drank nor smoked tobacco, and above all that I had a wonderful constitution and lived in the open all my life, I would have died. He laughed and said that I was as strong as steel. We were great friends before. My home at Pu'u Hue was home to him. I loaned him a horse to use for his professional service in the district of Kohala. During the week-end he would come to the ranch and spend Saturday and Sunday, returning Monday morning early. Many a time his horse would come to the gate without a rider which was a sign that he was drunk and had fallen off. The horse came back to his stamping ground to let us know that the doctor was on the ranch sleeping with the cattle. I always sent out cowboys to pick him up and bring him home to us. For this he was grateful and when the opportunity came he surely made up for it. He said that in my condition no other professional surgeon would have amputated my hand above the wrist. Knowing how badly infected I was with gangrene, professionally, he should have amputated my arm at the shoulder. But knowing how useful my elbow would be in my life, he took the chance because he knew that I was constitutionally strong. He was a true friend and I was grateful for his benevolent deed.

Puuwaawaa

By Eben Parker Low

In 1893, Eben leased a tract of land at Puuwaawaa with Robbie Hind and began to ranch there. The following is the story of shipping cattle from the ranch after its first year.

In the first year of business, Low and Hind easily made their lease payments, and soon the ranch was shipping cattle off island from Kiholo beach, eight miles straight down the slope of Mauna Kea. But there were problems.

“I soon found that the steamship people were so all-fired careless about getting to the shipping point on time that our cattle often suffered from waiting in the shipping corrals. It was more than disappointing, when after a successful drive, we sat there watching the cattle in the pens while the blasted ship failed to appear. I complained many times to the Wilder Steamship people, and sometimes got Captain Wilder himself or Charlie White in the office to see that the promised steamer was on time. Then, in gratitude, I would send them some fine big fish or roasts of beef which they could enjoy. But again and again, the ship would keep us waiting. I began to figure some other way to keep a proper schedule. I could contract with the rival Inter-Island Steamship people, who promised that they could meet a herd at any designated time. But in order to do this, it would have to be a different shipping point at Pulehu in Ka’u. Everyone called the trip impossible, and even I hesitated to drive the cattle over further lava flows. But at the same time, I was by no means going to allow anyone to push me and my cattle around.

“On a moonlit night, after waiting at Hawi until the cattle were bawling and so restless that they were beginning to attempt stampeding through the corral fences, I flared up. We made that "impossible trip" to Pulehu and the Inter-Island ship anchored off shore promptly as had been promised.”

“With that trip to Pulehu, I showed everyone I was in no humor to be neglected at any time. That trip won admiration and respect for us at Puuwaawaa Ranch. There was no further delay or trouble afterward. Of course I had to build my own pens at Pulehu but it was worth the extra trouble and expense.”

Getting cattle to the market in Honolulu was significantly more complicated than taking them to nearby Hawi. There were no piers. Cowboys took the animals through the surf and tied them by the horns to the side of waiting whaleboats. The boats were then hauled out to the ship by a stout hawser and the animals were slung aboard with a cargo winch. On one such occasion, Eben described loading cattle aboard the Inter-island steamer Kilauea.

“Captain Freeman had the ship anchored about a mile off shore. It was a real he-man job to get the cattle out to that ship. The steer had to be roped, dragged down to the beach, swum out to the long boat and tied to the gunwale. The longboat took four to five cattle on either side. At the steamer’s side, each animal is hoisted up on deck and herded into stalls. On this day, a steer fell into the sea on its way up. The captain refused to send a long boat after it. He was still bleary eyed from a night’s jolly time ashore in Kawaihae. Jim Purdy stripped down to his britches and started off after that steer. Imagine such a swim in high seas and shark infested waters a mile offshore. But Jim gave no thought to anything except his work of bringing that steer to the ship. He reached the steer and dived under it to get the sling rope untangled from his forelegs. Then he climbed onto the steer’s back, lay down along its spine, took the horns in his hands and steered that animal ashore by hand pressure on the horns. Let Ripley publish this one. It does sound like a “Believe It or Not” tale, but there were many eye witnesses with me and they can all vouch for its truth.”

The following is a draft of my new book about Eben

The Ohana

Chapter One

In 1856 a young man dressed in flannel pants, suit coat, tie and Panama hat drove a horse and buggy out of the town of Waimea on the “big island” of Hawaii and headed up Puu Onoho road which was then not much more than a foot path. He crossed a lightly treed prairie. To his right the volcanic cone of Mauna Kea swept in a gentle arc 14,000 feet into the sky. He turned around from time to time perhaps to admire the scenery or, like a sailor navigating a grassy ocean, to take ranges and bearings that would allow him to navigate home if he lost the thin traces of the road he followed. Although it was not obvious, he was a seaman who had crossed many oceans and had seen the hoary frost on the black face of Cape Horn. After a few hours of slow going, he passed a ranch house surrounded by a partly completed stone wall. This was the home of John Parker, his client for this day’s work, but he did not stop.

Soon enough he reigned in his horse and stepped down from the buggy. Reaching into the back he found a varnished wooden case which he removed and placed carefully on the tall pili grass beside the road. He took out a tripod, walked a few paces, splayed its wooden legs and adjusted knurled metal knobs to bring the apparatus to about the height of his chest. He opened the box. Inside, nestled in a cradle of curved battens and felt, was a Field’s Philadelphia theodolite. He placed it atop the tripod and made it level with the use of a bubble of air trapped within a gently curved glass vial. Now, sighting through his telescope, he was certain that his ray of vision was a perfect tangent to the earth’s curve. He began to lay order upon the tilting prairie around him. The man’s name was John Somes Low. He was my great grandfather.

Low was one of two or three surveyors in this part of Hawaii. It was a kind of miracle that he was there at all. Later, some would say it was a tragedy. For at least a thousand years the land around him had been divided into portions by memory. The boundaries were known, if fluid. They changed with the ascent and descent of noble Hawaiian families during flickering dynastic wars. The metes and bounds were kept by old men in their heads - men who also kept there the genealogies of their princes and perhaps the knowledge of star paths to distant islands or the cures for illness. They were called kahunas, masters of knowledge, a word that also meant “priest.” The portions of land these men filed in memory were sometimes small parcels of a dozen or so acres called kulianas, tracts farmed by Hawaiian commoners. Or they might be much larger pieces - anywhere from hundreds to thousands of acres - controlled by Konohikis or noble overseers. The old men also mentally recorded the bounds of the kings, or moi; and the ali’i nui, the very high chiefs. These lands could have extended over an entire valley – perhaps 50,000 acres – or an entire island. The way that land was parceled out in the Kahuna’s mental maps was a schematic of Hawaiian social classes, although you could not say that any of these groups owned the lands because there was no such thing in Hawaiian thought as “ownership.” The land, if it was owned by anybody, belonged to the gods.

Low began the methodical process of survey that he had learned as a student at Harvard’s School of Engineering. In New England such an activity would have been so commonplace as to be unworthy of note. But here this simple act was the culmination of a profound change in the way that people thought of their land. It would put the kahunas out of work. It would destroy a system of governance that had ordered the Hawaiian people for hundreds of generations. It was the culmination of an Anglo-Saxon urge to not just lay order upon nature, but to control it, although John would surely not have seen it this way. That’s not to say that he was unaware that a kind of revolution was going on, it’s just that he was in no position to benefit from it.

As he moved across the land from station to station, Low entered into an easy rhythm of sighting, measuring distance and sighting again. He read the scales of his instrument carefully, at least twice, and entered them in his notebook in small uniform figures. Even a small error, a matter of a quarter of a degree or so, would have a big effect because he was surveying a vast tract of land, 640 acres - a mile square.

The work required precision but little thought, freeing his mind for rumination. He considered his future which was now bound up in the hundred acres of land he had recently leased from the King. Two acres were cleared and planted and, as he wrote to his father in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the trees were “growing finely. Next Spring,” he continued, “I intend to plant some ten or fifteen acres, perhaps more.” It could not yet be called a plantation, but it was a good beginning. When cleared and fully planted with coffee trees, he expected the land would yield about twenty tons of coffee beans each year. At twelve cents a pound, that would bring in 4,800 dollars. The lease was fifty dollars a year. The cost of six Hawaiian laborers was three hundred and sixty dollars. A profit of 4,380 dollars. That was, of course, in the distant future. He would need three years to clear the land and plant the trees, then a few more years for them to grow to maturity. Say six years in all. “There is demand enough for coffee,” he had written to his father, “for it takes some beans to supply 500 whale ships and there are very few (beans) raised in the island. A great many are shipped from home to supply the demand and If I can’t compete with home with such land as there is here to raise fresh beans from it will be queer.” The endeavor was not quite so certain, of course, but John was presenting it optimistically because his farther (one of the richest men in Gloucester) would scrutinize his new business venture with a Yankee’s jaundiced eye. In the meantime there was a lot of surveying to be done, thanks to the new laws allowing foreigners like his client John Parker to buy Hawaiian land in fee simple.

Although Americans considered the concept of purchasing land in “fee simple” to be as essential to life as oxygen, it was a perplexing concept for Hawaiians. The land that John surveyed, for example, was part of an immense tract that Hawaiians called an ahupua’a. It bore a name known to the Kahunas, Paauhau, and was the property of a high chiefess, Keohokalole, the mother of the heir apparent to the Hawaiian throne. Paauhau was like thousands of ahupua’as in Hawaii. It extended up a deep valley from the ocean to a mountain peak. Its borders were the ridges on either side of the valley. Most ahupua’as were pie-shaped, with the crust along the shore and the sharp end in the mountains where the ridges joined. In the Hawaiian scheme of things, Ahupua’as were a natural way to divide the land because it was so easily defined – a valley and its shoreline. It was also natural in a larger sense because it contained all the resources that its residents would need. Water cascaded in spectacular falls from the mountain peaks, gathered in deep pools and abraded its way through lava to form streams and rivers which were channeled by the natives into their lowland taro fields. The temperature gradient from shore to mountain peak enabled the cultivation of numerous crops such as taro and avocado that liked the lowland heat and sweet potatoes that flourished in the cool uplands. Pigs, goats, native deer and wild cattle also dispersed themselves according to altitude and vegetation along the surface of the tilted pie-shaped terrain. Villages were located along the shore where seafood was plentiful and canoes could be drawn up easily. In this crenellated world, canoes were not just for fishing - they were also the best means of transport from one ahupua’a to the next.

The Ahupua’a was not just an ecologically viable land division; it was a map of political and social power. Each pie-shaped territory was the provenience of a high chief. Under him (or her) the land was divided into property cared for by the konohiki, who supervised the work of the commoners, who actually farmed the land. The ahupua’a was a topographical map of Hawaiian society with the king at the top, the high chiefs next, followed by the konohiki and the commoners.

My grandfather had been in Hawaii for a little more than a year and he understood this land tenure system in the simple manner in which I have described it, but the system’s subtleties escaped him. It was hard for John, or any foreigner for that matter, to imagine how Hawaiians felt about the land. For one thing, most of the haole who lived in Hawaii at this time were wanderers. They had departed their homes to seek new lives. Most Hawaiians, on the other hand, had lived in a single ahupua’a all their lives. They could recall stories told them about the land by their fathers and grandfathers. And their Kahunas remembered stories that went back to the beginning of time, a hundred generations or more, all of them associated with particular events and people and places. And so in each ahupua’a the land had become encrusted with meaning that shaded into myth, none the less powerful than if the events had happened there yesterday. It was a Homeric topography which perhaps an Athenian might understand, but which eluded most of the haole although they may have prided themselves in their philosophical descent from the ancient Greeks. It was also a vision that was doomed.

The first stroke of death occurred when King Kamehameha III signed into law a measure for “the quieting of titles to land.” It was a strange way of putting it, for the “title” to land had been quiet for a thousand years. Although individual Hawaiians might inhabit the land, even inherit the right to use it, the real title to it resided in their gods. Their ownership of the aina, as the Hawaiians called the ground upon which they walked, was presumed to be eternal. But the coming of the haole had seemed to shift the firmament in which the gods dwelled and with that movement, slight at first, came the commotion that must now be quieted.

The first haole to move to the islands, men like John Parker, were at first content to be agents for their Hawaiian hosts – managing their ports; organizing the trade in sandalwood, hides and meat; and tending small farms on lands generously given to them by their Hawaiian overlords. Land tenure at that time was basically feudal. Title (meaning the right of usufruct) resided always in the King or paramount chief, who apportioned it to a group of high ranked ali’i, who, in turn, set aside small plots for the commoners. The death of a king was accompanied by some reshuffling of land, but the system worked smoothly enough for over a thousand years.