Fine Arts Press Materials

A unique photographic style

Sam Low combines the aesthetic of a painter with an ethnographer's instinct for human detail. This unusual blending of art and science comes from his background as a Harvard-trained anthropologist/archeologist, a documentary filmmaker and photojournalist. Low was introduced to the world of art by his parents – both watercolorists - during Vineyard painting trips.

“Both my father and mother were well known island artists and I often accompanied them to places all over the island where they set up their easels. I grew up with their artist friends – Thomas Hart Benton, for example, and the actor James Cagney who was a gifted amateur painter. The island was a community of artists in those days and I inhaled that atmosphere, but I never really thought I would venture to join in it – until now.”

Low has spent most of his life as a teacher – both a college professor (anthropology) and a producer of documentary films for such venues as National Public Television and the Discover Channel. He used his artists' eye to capture details of daily life in a Peruvian squatter settlement while researching his Ph.D thesis and to film an eight part PBS series on the Maya Indians of Mexico and Central America , among other documentaries.

“My photography and cinematography was always in the service of a human story and it was always abetted by words – either film narration or extended captions. Now I am cutting myself loose from those crutches and taking up my camera to capture a single essential moment that has to stand alone.”

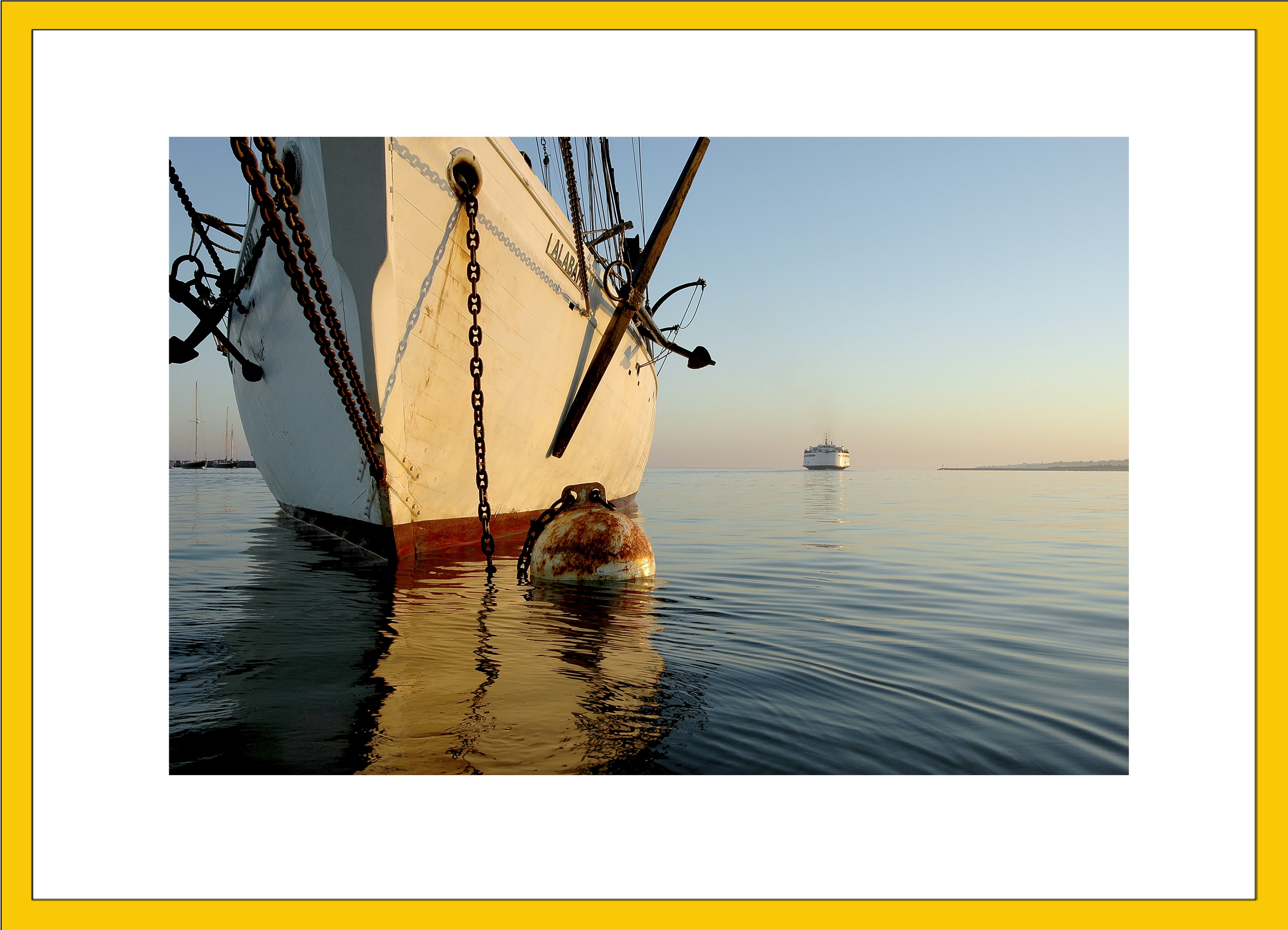

Low's photographs employ a narrative style that stems from his sense of human history. “ Home Port ” - a portrait of the Islander and the schooner Alabama , speaks of the old and new – conjuring eras of sail and steam and diesel to evoke a wider historical perspective.

“Early shift at Mocha Mott's” is an example of Low's ethnographic sense – capturing a moment of rest and anticipation and a simple bonding among employees waiting for the onslaught of customers.

Low's perspectives are unusual. He captured “ Home Port ” from a Kayak by placing his camera on the water's surface to produce an unusually low angle that balanced the shimmer of water and the drama of open sky.

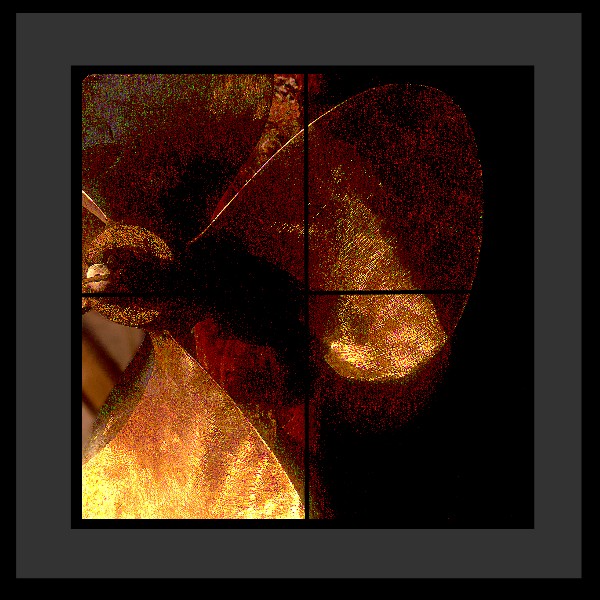

Other photographs are “realistic abstractions” – a tight focus on elements of the scene which convey a strong sense of the larger image. In “Red Boat,” he zooms in on the stern of a brightly painted dinghy, capturing a flowing rhythm of sand that suggests waves. “Propeller,” is an abstraction of golden curves that suggests gossamer wings and a flowing field of energy.

His work is extremely graphic, employing strong primary colors and light and dark contrasts to attract the eye, such as in “Morning is Breaking” – a brilliant sunrise behind chiaroscuro phragmites' tassels in the foreground.

Low has worked hard to find a way to present his photographs in unusual frames, employing a style he invented of “floating” his photographs off a black background, encompassed by a dark void all around them and a black mat and frame which provides an intriguing play of light and shadow.

Low has lived on the island almost all of his 62 summers. As a teenager, he probed the depths with an aqualung to explore shipwrecks such as the Port Hunter in the “graveyard” of Vineyard Sound. He has hiked the island and swam from its beaches – developing a love affair with the folds and creases of her landscape. Many of these moments are captured in his Vineyard Gazette photographs and his many articles for Martha's Vineyard magazine.

Because Low handles all the aspects of his photography – from image capture to printing and framing, he is able to make these unusual photographs available at a very affordable price.

Sam Low resume

1942 – born in New Britain , Connecticut and spent his first summer on Martha's Vineyard .

1952 – set up his first darkroom and dabbled in amateur photography.

1964 – graduated from Yale University and reported aboard a naval Vessel operating in the Tonkin Gulf .

1966 - 1974 – was a diver/archeologist on underwater excavations in the Mediterranean (three seasons) and completed his Ph.D. in anthropology at Harvard where he spent time learning the art of ethnographic filmmaking.

1975- 78 – college professor at Hunter College and Bowdoin.

1978 – 1995 – producer/director/writer of many PBS films and partner in Cambridge Studios in Massachusetts .

1995 to present – photojournalist/writer and (recently) fine art photographer. He has written pieces (with photo coverage) for more than a dozen magazines and newspapers. Sam is currently completing a book on ancient Polynesian voyaging and navigation and his adventures sailing aboard a replica of an ancient Polynesian voyaging canoe in the Pacific for the University of Hawaii Press .

Sam Low – A love affair with Digital Photography

A Paradigm Shift

A year or so ago, I purchased my first digital camera. I had been waiting for the prices to come down and I watched them go from twenty thousand dollars to one thousand dollars for a good camera over a period of about 7 years. When it got to one thousand, I purchased a Nikon D70 which took all of my old Nikon 35 mm lens. The switch to digital was nothing less than a paradigm shift – a whole new world for me.

With 35 mm, I would go out and shoot and come back and mail my rolls of film off. A week or so later, I got them back. Often it took more time – as much as a month – because I waited until I had a number of rolls to develop before sending them off. At any rate, between the taking of the picture and seeing it, I had lost the initial bloom of creativity. And the photographs were always slides so I had to look at them on a light table through a magnifier – a process that distanced me from the image.

To make a print, I had to choose the image and send it off again to a custom lab, or, if one was available – drive to it. Later, the proofs came back. They are never the way I initially saw them – too much red or blue or whatever. So I send them off again and wait for corrections. The process is long and dreary and frustrating – and it militates against actually making prints. Most of my photographs remained slides – stored away for the occasional slide show.

With digital – I can go out and shoot, often early in the morning, and return home to load the images into my computer. While they are downloading I brew some coffee. By the time I have poured my first cup, the images are up on my computer screen – vivid, exciting, and immediate. Then I go to work on them.

In Photoshop – a computer program – I can crop them, burn in details or hold back places where I may have too much light – just like they do in a darkroom. I can adjust contrast and color and I can crop them as the folks in the custom lab will do – only I am doing it myself and I can see the results instantly on my computer screen.

Then I make the prints myself – selecting different kinds of paper and printing techniques to get the effects I want. The stacks of proofs pile up on my desk until I am happy and then I print the image to the size I want and frame it.

Within a few hours of taking the photographs I can see the results hanging on my wall. And seeing them on the wall confirmed my first fantasy – that I would someday be good enough to hang my own work alongside the watercolors of my parents. They seemed to fit in with them – to hold their own. That is when the idea of an exhibit first occurred to me. I don't think it would have been possible to conceive of actually showing my photographs without having gone to the digital process. Being able to print and see the results immediately allows greatly expanded freedom to explore new avenues of expression.

Creativity happens when the right side of your brain – the rational side - talks to the left – the intuitive side. Out of this conversation comes a blend of reason and intuition that sparks news ways of seeing things. The “digital revolution” is not about cameras and printers and software – it is about how all those innovations have created a “whole brain” approach to imagining the world around us. In my view, digital photography has provided the photographer with the means of taking complete control of his or her images and by so doing has allowed for a greater impetus to experiment.

Framing the Picture

One of my mentors believes that the frame should be as simple – and as inexpensive – as possible in order to neither detract from the photograph itself or to add to its expense and decrease its marketability. This is a valid point of view and a number of my photographs are framed this way.

On the other hand, I have experimented with great delight in alternative presentations of my photographs – with using the frame as an integral part of the photograph itself. While experimenting with a variety of prints, I came upon the idea of “floating” them on a black background with a gallery running around the print – a space to separate it from the black mat and frame. The effect produced is a series of shadow lines that enclose the photograph and give it greater impact while, at the same time, lifting it off the background and causing it to appear suspended in space. Creating these frames is time consuming and expensive – but I believe they create an overall package that enhances the impact of the photograph.

I have also experimented with segmenting the photograph into both triptychs and separate panels in which the photograph is divided into quarters. The first experiment took place with a large photograph of a propeller. I found that by cutting the photograph into quarters, mounting it on board and then “floating” it in the manner I have described, I created an effect that I believe enhances the image. For one thing, I am enlarging the image to the point where the pixels begin to show. This is usually considered a “no-no” by photographers who want the utmost clarity in their images. But I found that the “pixilation” produced an effect that made the propeller seem to be moving within the frame – the reflection off the blades became pixilated clouds that suggested motion. Considering the quarter panels, I saw them as suggestive of the square pixels that make up the photograph itself – calling attention to the technology that produced the image – and the motion effect. In my estimation, this added another dimension to the enjoyment of the photograph. Finally, the black lines that divide the photograph into quarter panels tend to arrest the turning motion of the propeller and provide drama. All this may be in my head alone – none of it may be perceived by the viewer – but it is an experiment that pleases me.

Without the ability to produce everything myself in the digital process - from camera to print – I would probably have never thought of this unique way of presenting my photographs.