A much shorter version of this was published in Sailing Magazine

Saturday – September 9

“It's up to you. Each captain will decide, but if it were me I would wait in port until the Meltemi dies down”

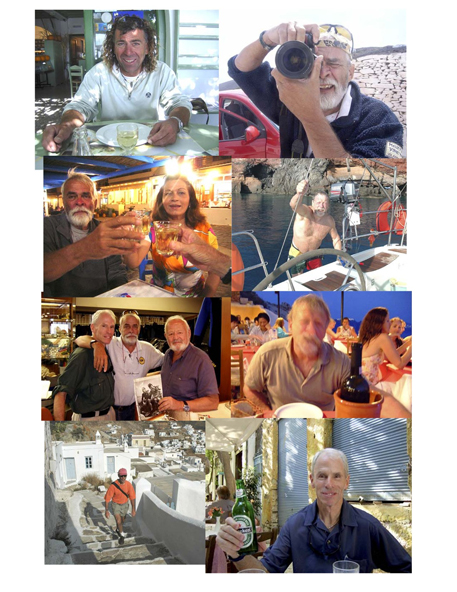

We are attending a captain's meeting in the Acapulco taverna overlooking the sheltered harbor of Finikas , on the Greek island of Syros , home base for Moorings Yacht Charters in the Cyclades . We have come here to spend two weeks sailing through a necklace of islands in the central Aegean , south of Athens and north of Crete . I will captain Asteria, a 43 foot Juneau sailing sloop. My good friend, Terry Vose, and my cousin, Kim Hart, will be crew.

On the car ferry from Athens to Syros , we could see the wind was brisk, maybe 20 knots out of the northeast, uncomfortable sailing but certainly acceptable. But now the weather is predicted to deteriorate rapidly. A Meltemi is moving in, bringing gale force winds for three days. None of us is pleased about staying in port, but a gale is not to be fooled with. I confer with my crew. We will look at the weather tomorrow and then make our decision.

During the evening, while dining at a taverna overlooking Finikas, the wind dies. But at three AM , I am wakened by gusts howling through Asteria's rigging. We are in the lee of surrounding mountains. If the wind is this strong here, it must be blowing 40 knots outside the harbor. I check our mooring lines.

Sunday – September 10

At dawn, the sky is clear but on the horizon outside the harbor the sea rages under a scrim of haze stirred by the Meltemi.

“We're not going anywhere today,” I tell the crew.

There is no disagreement.

The three of us first joined in the Mediterranean in 1967 to help excavate an ancient roman ship that sank off Torre Sgaratta on the Italian coast in about 180 AD. Expedition leader, Peter Throckmorton, was a well known marine archeologist. He had discovered dozens of sunken ships in the Mediterranean including one at Cape Gelidonya , the earliest wreck discovered up to that time. That ship was carrying bronze ingots from Cyprus when she struck a reef on the Turkish coast and foundered, taking to her final resting place a time capsule from the Bronze Age. The Torre Sgaratta wreck sank in Roman times. She was carrying a cargo of marble coffins from turkey to an unknown Italian port when a fierce storm struck.

“By midnight , his ship laboring heavily, the anxious captain would have put lookouts in the rigging,” Peter wrote in a 1969 National Geographic article. “At dawn they sighted land. With her great square sail, and her heavy load, the ship did not go well to windward. She was trapped in the Gulf of Taranto . …As the gale increased, the first anchor dragged and the doomed ship inched toward shore. The first anchor and then another were lost as the stout cables broke. In the deepening darkness, the big ship worked inexorably toward the six-fathom line, where the long seas curled to break. The gale shrieked louder. Nothing to do but cast out all remaining anchors and pray, as St. Paul did in like circumstances. If the vessel survived until daylight, there was a chance—just a chance—to run her ashore, accepting the loss of ship but saving the lives of those aboard. It was the captain's last gamble: His ship foundered that night, five hundred yards offshore.”

The gale that now shrieks across the Aegean outside the sheltered harbor of Finikas is stirred by an immense low pressure area that forms in the summer over Turkey and a high pressure area over the Balkans. These two massive systems churn air between them into the open Aegean where they can blow undisturbed over a hundred miles of ocean. Within only six hours they can produce wave heights of ten feet. An average Meltemi reaches a force of five to six on the Beaufort scale (winds of 19 to 31 miles an hour) but the winds are now predicted to reach force 8 (39 to 46 miles an hour) which is defined as a gale. Once the Meltemi sets in, it can blow steadily for three to five days. We have heard reports of yachts being marooned by such gales in Finikas for an entire week.

“What the hell,” I tell the crew. “We're in Greece so let's do some exploring.”

*****

The prehistoric settlement at Chalandriani lies in a cradle formed by two mountains. Thistles stud the hills and serpentine stone walls spill off high crags. The landscape is arid, umber colored. Nothing seems to grow here except a few olive trees and stunted grape vines. A Bronze Age settlement was first excavated in this place in the 1800s. We see archeologists' pits and tattered labels marking stratified deposits from a more recent excavation.

This was a graveyard from an early “Cycladic” culture which thrived from about 3300 to 2000 BC. The people here raised sheep, goats and pigs and cultivated grain, grapes and olives. They were skilled sailors who traded throughout the Mediterranean – with the evolving Minoan civilization in Crete, the Greek Mainland, Troy in Asia Minor and as far even as the Adriatic ocean and the Danube Basin.

From the six hundred or so graves here, archeologists excavated many examples of the now famous Cycladic figurines – elegant shapes with folded arms and upturned stylized faces – that were at first considered ugly when unearthed in the late 1800s. But with the increasing popularity of modern abstract art, they became widely sought after by collectors. Unfortunately, this led to astronomical prices on the art market and widespread looting of grave sites. Above the cemetery is a small walled citadel about 150 feet across surrounded by defensive walls and six towers. Inside the walls, tiny houses were connected by narrow alleyways.

As we work up the path from the site to our parked car, gusts of wind rush up from the distant sea, almost bowling us over. To the west, the clouds are dark. To the east, under the late afternoon sun, they shimmer. We watch heavy rollers marching under a horizon lost in salt spray and we are glad not to be out in them.

At 7 PM we tune in the Greek weather report on VHF channel 3, snug in the main saloon of our sailboat.

“In the southeast and southwest Aegean , the winds will be north-northeast gale force 8.”

At night, the wind worries the rigging of yachts moored beside us. It is strangely cold. We sleep under blankets – uneasily.

*****

Monday – September 11

Fishing boats bob at their moorings in Ermopoulis, the main harbor of Syros . No one goes out. Ferries run late – if at all. In a taverna overlooking the harbor, umbrellas dance in the wind. Long puffy clouds form over the mountains. Only three yachts are moored to the quay, rolling in swells stirred by the high winds. A large car ferry is tied up at the commercial pier waiting for the wind to slacken. We lounge over lunch, talking about the possibility of sailing to Mykonos tomorrow. Captain Giorgos Rigoutsos has a yacht to pick up there and has volunteered to go with us.

At eight PM , the weather report tells us the wind will shift to the north northwest and drop to force seven generally, but in places it will still be gale force eight.

*****

Tuesday – September 12

At nine AM , we set out from Finikas with Giorgos aboard as captain. None of us have been to sea before in force 8 conditions. In the lee of the island – under storm reefed main and a handkerchief of genoa - we gain confidence. But when we move past the island's eastern tip, the Meltemi bears down on us and we confront the full force of gale winds funneling between Syros and Tinos . The sea humps up into steep twenty foot swells. Spume blows off their tops and Asteria takes white water over her bow.

“We would never be doing this without you aboard,” I tell the captain.

“Amen,” say the crew.

Asteria slews between heaving swells as we head northeast toward Mykonos . I steer toward the southern tip of the island – seeking a delicate balance between too much and too little helm as we veer in the quartering seas. Remarkably, the boat seems at home here. She pounds only occasionally and shoulders aside the towering waves.

"Not as bad as it looks from the shore,” I tell Terry.

“Outstanding,” he replies.

Sailing these seas is not for beginners. In Maine , where I learned to sail, we would not venture out in winds much over 25 knots. Yet here we are sailing in 40 knots across a deep and unfamiliar ocean. The sky is cerulean blue and the sea is frothed white. The wind howls. Spray wends into the cockpit. We are wet, but comfortably warm under the bright Aegean sun. We relax. In the far distance, under a spume of salt spray, stands our next destination after Mykonos , the island of Naxos . Mykonos is not a favored by sailors. It is a tourist port, busy with shoppers by day and carousers by night. Yet as we arrive in the harbor, we are charmed by white houses spilling off the hills.

Harbors in the Mediterranean are often crowded places. Commercial vessels, ferries, fishing boats and yachts jostle each other for space at a tiny quay. To maximize the space, they employ what is called a Mediterranean moor by dropping an anchor and backing into the quay to tie up stern-to. It's a delicate maneuver. The anchor must be let go at a precise spot so as not to foul those of other yachts. Then the boat must be backed into a tiny place between them. Going astern, a sailboat like Asteria will first veer sharply to port under prop thrust. Only when you gain speed will she respond to her helm. The maneuver requires precise coordination between skipper and the crewman paying out the anchor chain. And it must be accomplished under the watchful eyes of other yachtsmen. On this approach, with the wind blowing our bow to port, I find Asteria does not respond as I expect.

“Giorgos,” I say, “Please take her.”

Giorgos backs Asteria neatly into her slip, ignoring the vituperation of a fat Greek aboard a large power boat who decries his seamanship in guttural and offensive language.

“I will speak to you when I am moored, my friend,” Giorgos responds.

Once securely tied up to the pier, we retire to a nearby taverna for wine and mezzi.

Wednesday – September 13

Clearing Mykonos harbor, we set a tiny triangle of genoa and surf fifteen foot swells frothed white. Between Delos and Mykonos , the sea begin to calm under the influence of a strong current running with the wind. Past Delos , we set course for Naxos , a thin outline under a long strand of cloud. The wind is astern and the boat swerves gently in seas now only eight to ten feet high. The sun sheens the ocean to starboard and Paros presents itself – a smudge against the horizon off our port bow. Other than the islands all around us, the sea is empty.

“We're alone in the Aegean ,” says Terry.

We let the jenny out. Our speed increases to 7.5 knots. Our spirits lighten on this sleigh ride to windward with Van Morrison and Neil Young piped into the cockpit.

Seven miles out, Naxos opens itself to us – a confetti of white houses spilling off high hills. The island humps against the horizon to port, a series of high peaks shrouded in cloud. Paros shines in the sun path to starboard.

“If I am uncomfortable with a Med-moor we are going into the anchorage,” I tell the crew. “But if the wind is right we'll try it.”

“No problem,” is the response.

We have practiced all kinds of mooring procedures with Offshore Sailing School – but on a scale of one to ten – they were all a three. Trying to moor stern-to in twenty knots of wind is another matter altogether. It's a ten. Am I concerned? You bet.

Sailng coastal New England waters and through some of the Pacific, I am accustomed to large harbors with plenty of room to maneuver. Naxos marina – in the heart of the town – is tiny. There is barely enough space to turn the boat. With trepidation, due partly to the strong north wind, we enter the harbor and look for a place at the quay. The few available have almost no room for mistakes and leave us bow into the wind so that if we drag our anchor we will be on the pier.

“Makes my sphincter pucker,” says Terry.

“Me too,” I reply.

So we head out to the exposed outer harbor where the Meltemi whistles over the breakwater. Once anchored, Asteria swings wildly from side to side in the gusting wind, pivoting on her narrow fin keel. At one end of our swing, we closely approach another anchored boat so we move out into the harbor where there is more room to swing.

The sun descends over Naxos and the lights of the city gleam in the darkness astern.

The Meltemi blows chill. Surf pounds like a giant heartbeat. The sky overhead is blanketed in stars. We are tired and turn in early after our first simple meal cooked aboard. It has been a good day.

*****

Thursday – September 14

We spend a restless night swinging at anchor with the sound of the rushing wind keeping us company. Terry and I check our anchor at regular intervals.

In the morning, after a leisurely breakfast aboard, we clear the harbor, set the jenny and surf down the channel between Naxos and Paros . A low layer of cumulus clouds gather over the islands. Ten foot seas break behind us yet we are warm and relaxed in the bright sunlight. According to our GPS, we are making 7.5 knots – 9 at times. We see Ios rising under haze in the far distance and Iraklia in the gleam of the sun's path ahead. Swollen clouds linger over the islands' sensuous hills. Suddenly, five large dolphin politely announce their presence by cavorting a hundred feet on our port beam. Then, in pairs and threes, they close in to play in our bow wake. They swim powerfully. Almost touching the stem, they roll and cavort, then speed forward to jump clear and swerve off astern to return again.

“That's good luck,” says Terry.

After about 45 minutes, they tire of us and we are again left alone in an empty sea.

Terry alters course for the pass between Iraklia and Schinousa. We enter the lee of Naxos . The wind and sea calm.

“The wind must have come down fifty percent it the last three minutes,” says Terry.

“What a day,” says Kim, “and we're just beginning.”

*****

“You are good guys,” Captain Giorgos told us after a few glasses of krasi in the taverna in Mykonos , “So I'm going to tell you about a secret place.”

Iraklia is not so secret but it is very special nonetheless. We enter through two rocky arms that jut into the sea to find a tiny harbor with just enough room to swing the yacht before fetching up on a white sand beach. We ready the anchor. There's a small quay to the left and the rocky coast to the right. In the shelter of the quay, a dozen fishing caiques are tied up – their glistening white hulls trimmed with yellow and blue strakes. They are old fashioned double enders with graceful sheer – rare now on the Greek mainland. When I first visited Greece more than 40 years ago, every harbor was crowded with them.

“Iraklia is like the old times,” Giorgios told us, and so it is.

We moor in the center of the harbor and set a stern anchor to temper Asteria's tendency to wander. The hills protecting us from the Meltemi are capped by orderly rows of dry-laid stone walls. We have arrived at four PM and the harbor is quiet. Nothing moves. Everyone must be asleep. We can see three tavernas, closed for the moment, and the blue dome of a chapel. A winding road disappears over the crest of a hill.

Swimming the anchor chain in clear water, I see Asteria's keel with about five feet of clearance over a smooth sand bottom. The water is cool and sleek against my skin as I check the anchor. It is deeply buried in the sand. Perfect.

Kim and Terry go ashore in the dingy. I am content, beer in hand, to lie on deck and contemplate our good fortune. Perhaps it was the dolphins that brought us here. A caique puts to sea, the deep throb of its engine echoing from the surrounding hills. A woman swims in the still waters off the white sand beach. A man strolls along the quay and stops to inspect the mooring lines of a small fishing boat. Another man in a striped shirt fills a caique with diesel from a 40 gallon drum. In two hours, this is the total of all activity I observe from my perch in Asteria's cockpit. Suits me fine.

The tourists who stay in Iraklia are from all over Europe – Norway , Italy , Holland , the UK – and they come for weeks at a time to enjoy the peace and quiet of this out-island. Islands like Mykonos offer a thronging café life where the bars are open all night. Here, serenity and friendliness are the treasured amenities.

*****

Friday – September 15

“Asteria, Asteria.”

A booming voice rouses me from a nap at 3:30 in the afternoon. It is the captain of a large water tanker moored across the quay.

“Are you ready for your water?” he asks as I gain the cockpit.

We met the captain of “Giorgos” – a 150 foot Russian built tanker - in the taverna at the head of the harbor when I inquired how we might obtain water.

“How much do you need?” he asked.

“One hundred fifty liters,” I replied.

“I bring 500 toms to this island every ten days,” he says, “so, please, I will fix a hose for your 150 liters.”

The kindness we have received on this trip reminds me of an earlier time – of 1964 when I made my first trip to Greece to join an archeological team diving on the ancient harbor at Krenchreai.

Earlier in the day, a young truck driver offered to take us to the ruins overlooking a long strand of beach at nearby Livadhi. Terry had engaged him in conversation during the hubbub of the arrival of an interisland ferry.

“Can we pay you to drop us off and pick us up,” he asked.

“I will drive you, but I don't want any money,” he replied.

At Livadhi, above a crescent of white sand beach, we find rude stone walls surrounding a tiny settlement crammed along narrow alleys. Some of the building blocks are smoothly quarried white limestone, probably from an earlier classic Greek temple which the villagers scavenged to throw up the ramparts. Underneath the houses and in circular structures, we discover cisterns which stored water for a prolonged siege. The ruins are a somber reminder of a lawless period in the Mediterranean when no single power policed the seas. During the rise of the Cycladic culture there is evidence of warfare – settlements moving off the exposed coast to fortified hill tops like Chalandriani, for example. But for a time, under the sway of succeeding civilizations – Minoan Crete, Mainland Greek (including the empire of Alexander), Roman and Byzantine - the seas were policed by naval ships. With the fall of the great empires, the islands fell under the loose control of Italian city-sates such as Venice and Genoa , but there were long dark periods when no central power ruled over these tiny islands. Pirates swept down on coastal cities. The inhabitants responded by taking to the hills for protection. The guidebooks tell us that these ruins are a mix of Hellenistic and Venetian settlements and a more recent occupation in the mid 1900s.

*****

Saturday – September 16

In the morning, the wind slacks, then almost dies. This is an unexpected blessing. A spot has opened up on the quay and we decide to attempt our first Mediterranean moor. This usually requires running forward of the spot you will tie up to, dropping the anchor and backing down while letting out chain – coming to a stop three feet from the cement pier. It sounds simple but a yacht like Asteria tends to turn to the left due to the thrust of her propeller until she has gained enough speed so the rudder will have an effect. The path to the quay is always an “S” curve – first left then right and then – hopefully – straight in. Too fast and you may hit the pier, too slow and the wind may blow you off to either side, in this case into a gaggle of boats to port or shallow water to starboard. You don't even want to think what might happen if the anchor windless fails.

Yesterday, with the wind blowing 25 knots, I practiced backing the boat in a nearby cove. Asteria's bow is very high so it acts like a sail, turning the boat on her fin keel. In a strong wind, by combining prop walk and the sail effect I found I can back straight only if the wind is ever so slightly on the starboard side. Doing this maneuver over and over inspired some confidence, yet even in today's calm conditions I am nervous. I feel the eyes of fishermen mending nets as we maneuver to drop anchor, almost touching the bow of a moored fishing boat.

“Let her go Terry.”

Backing down with the rattle of the chain going out, Asteria swerves left, then right, and finally settles down to happily follow her helm. Two lines go ashore. Terry stops paying out the chain. We are moored.

“Nice job,” says Kim.

It is a victory – of sorts - but there is no wind and we are in a village of friendly souls. What will it be like to moor Asteria in a crowded harbor with the wind blowing like stink?

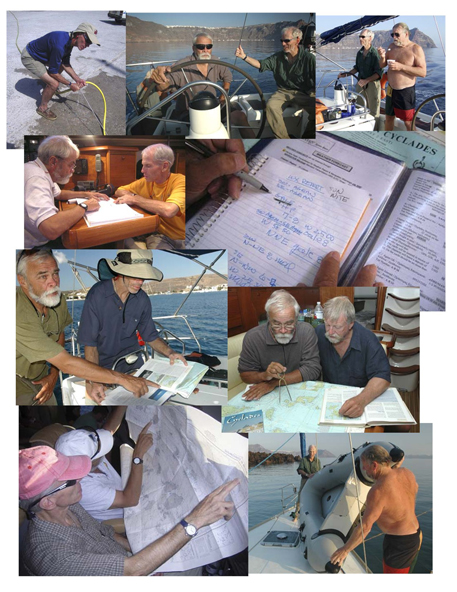

Later, grouped around a chart of the Cyclades and the Greek Pilot Book, we plan our next few days. Tentatively we select Folegandros, Milos and Sikinos as stops on our return path to Syros .

“South winds are coming on Sunday or Monday,” the water tanker captain told us. If so, they will speed us along. But as we look out to sea on this night there are no signs of wind at all. From too much wind to none in such a short time. What's next?

*****

Sunday – September 17

During the night, I dream of Santorini, one of the most storied islands in all the Cyclades . It was here that a massive volcanic eruption destroyed a thriving Bronze Age city. During the stormy first days of the week, I had decided that Santorini was out of reach - too far south. But with the winds now declining, I suggest we go there. The crew is enthusiastic.

At 7AM , we hoist anchor and proceed out of the harbor. The rising sun sheens the stubbled land to port. Outside, it is flat calm. Three tiny islands – Schinousa, Karos and Katofounisia - appear like the backs of giant whales, arrested at the moment of sounding to return to the depths. Ios presents to starboard and dead ahead lies Santorini, veiled in haze. The wind picks up once we are clear of Iraklia's wind shadow. We raise the main and jenny. We make seven and a half knots under sail. Soon, Santorini's caldera is clear on the horizon ahead. Houses on Ia, the northernmost point of land, glisten in the sun. We see the island of Therassia in the caldera. The wind accelerates. Asteria picks up speed. The sea is now studded with white caps.

Sailing into the caldera at Santorini, we enter a world of destruction - and rejuvenation. All around us, rising to hundreds of feet, are the dark scarps of cliffs, foreboding reminders that beneath our keel is a giant and still active magma chamber that has burst forth in eruptions small and large for thousands of years. In about 1650 BC, the ancient people who lived on Santorini began to feel the earth tremble. Archeological evidence suggests they packed up their belongings and fled. Unlike at Herculaneum which was destroyed by the Vesuvius eruption in 79 AD, no bodies have been found in the debris left behind by the eruption here. From the center of the caldera, where we now sail, a heaving body of fiery magma emerged sending spumes of smoke and ash fifteen miles into the sky, penetrating the stratosphere. The amount of ash, gas and volcanic rock ejected from the explosion was four times that of the famous eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. Cores drilled by scientists in the ocean floor and in Turkish lakes show the plume drifted east and northeast. The eruption created a giant tsunami, a wave estimated to be as much as three hundred feet high at its source, rushing out into the open Aegean . The wave swept through the Cyclades and reached Crete , probably destroying the Minoan fleet anchored on the island's exposed north side. Not many years later, weakened by the disaster, the Minoan civilization fell to their traditional enemy, Mycenaean invaders from mainland Greece . On Santorini, archeologists have excavated Akrotiri, a town that thrived just before the eruption and was buried by it, providing a time capsule of island life at the time. Scholars today debate whether the destruction of Santorini might be the source for the legend of Atlantis - a marvelous city that was destroyed by the gods because of its degenerate ways. In Timeaus, one of Plato's dialogs, he writes:

Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, and over parts of the continent… But, there occurred violent earthquakes and floods, and in a single day and night of misfortune… the island of Atlantis … disappeared into the depths of the sea.

The volcano continues to be active. Subsequent eruptions created the twin islands in the center of the caldera toward which we now steer – Nea and Palea Kameni. The most recent was in 1956. Yet in spite of the obvious danger, life continues on the ragged cliffs and in the interior of the island. We see the sparkle of whitewashed houses – the towns of Ia and Fira, resting above the dark crags. Ferries and cruise ships ply the still waters of the caldera. A large passenger jet arrives from Athens .

****

“Tin thalassa agapo”

We are moored on the quay of Vlikadha harbor on Santorini. Ashore, one hundred feet away, a yearly feast organized by the town's fishermen is in full swing. A violin surges free from the accompanying rhythms of bouzouki, guitar and mandolin. Teenage girls and boys whirl on a temporary stage. In front of the stage, villagers and tourists step out to the music. Spotlights, flares and fireworks light up the sky. A young couple breaks free and swirls intimately to cries of encouragement. They open their arms to the sky. They match steps, join and separate, in a dance that must be as old as Dionysus. The cadence of the music is intoxicating. It is old Greece – and in a place we least expected to find it. Later,

from Asteria's cockpit, we see the lights of tavernas above the harbor gleam in the still water. We are taken back a generation to when – as young men – we first visited Greece .

Monday – September 18

Outside the Archeological Museum at Fira, the streets throng with tourists laboring under backpacks and luggage. Busses jostle with cars and motorbikes. Merchants purvey Hermes watches and ersatz curios. Inside the quiet museum, Terry, Kim and I admire the artifacts of Santorini's past. Displayed in well lit cases are the evolving implements the ancient people of Santorini used during an extended period of time from the earliest Bronze Age through the flowering of their civilization just prior to the eruption that brought an end to it all. Many of the artifacts are from the nearby town of Akrotiri which was buried in ash and then opened like a time capsule by Greek archeologists. It is similar to Pompeii – a moment arrested by catastrophe – which provides a glimpse into the society of Santorini. Like the people of nearby Crete , they painted their walls with vivid scenes of everyday and mythic life. On one wall two fishermen display their catch, on others a fleet of ships set sail, warriors battle, a ship is wrecked, a young priestess holds a brazier of glowing charcoal, two children box, monkeys cavort, deer flee a lion, swallows feed their chicks. [1]

*****

We travel a winding road to the town of Magalohori perched on a hill above a surrounding plain. Serpentine streets wind capriciously past churches, alleyways and whitewashed walls trimmed in azure blue. Bell arcades frame the road which was made wide enough for laden donkeys and carts so only very small cars can navigate them. We pass through cobblestone plazas shaded by olive trees. We park our car in one of them and walk the somnolent village. Cats lie curled in the shade. Tall walls protect patios. Tiny windows are framed by brightly colored shutters. Bright blue and white Greek flags flutter in a gentle breeze.

“Traditional Greek Winery” says the sign. An arrow points the way up a narrow alley to the Gavelas family wine cellar.

“For three hundred years, we have owned this land,” says Santis, grandson of the proprietor, “and for all that time we have made wine here.'

The eruption that destroyed the ancient civilization of Santorini created a unique environment for growing grapes - chalk and shale beneath ash, lava and pumice. The arid climate stresses the grapes. No rain falls on the vineyards during the summer growing season so they receive a bare minimum of moisture at night from sea mist absorbed by the volcanic soils. The steady summer winds prevent moisture from accumulating on the vines during the day which results in high sugar and acid content. The grapes mature in a twined basket of vines – a stefani or crown – which protects them from the winds.

Early traces of wine production in Greece were found on the island of Crete - clay wine presses, wine cups, amphorae and wine seeds – from the middle of the 3rd century BC. Large vessels for storing wine were found in Akrotiri. Mycenaean kings drank their wine in elaborately shaped golden cups like that of King Nestor in the ancient city of Mycenae . Wine was traded throughout the Mediterranean by Greek merchants and many of the shipwrecks discovered by modern archeologists are laden with large clay vessels, called amphora, which were used to carry the wine. Most amphora were stamped with the seal of the city states that produced them and often with a seal of their maker, so when they are discovered in wrecks a trade route can be reconstructed.

Early in this century, the Gavelas family shipped their wine to the port of Fira in goat skins on the backs of mules where it was laboriously transferred to large barrels on caiques, then taken to Athens . Only recently have they begun to bottle and sell the wine themselves.

We sit at a small table with another couple, sampling the four varieties of wine offered by the vineyard. We are not oenophiles, but all of us like the taste of a wine called, simply, “Santorini.” It is rich with the flavor of lemon, pear and pineapple. Kim buys six bottles. We quickly consume one of them upon regaining the boat.

Tuesday – September 19

Terry goes ashore to return our rental car. Kim scrubs the decks until they shine. I wash our breakfast dishes and neaten the boat below. It is flat calm and hot. I walk to the nearby black sand beach and luxuriate in the cool sleek water.

We are tired of jostling tourists and the busy pace of Fira and Ia which we all recall from many years earlier as quiet backwater towns.

“We've got a sailboat,” I suggest, “so let's tour this island by sea.”

In the late afternoon, we are ghosting south in the caldera. The sun sets over Therasia. The sea is calm. To port, the city of Fira frosts the western wall. Below the town, a large cruise ship is anchored. We have had a good day exploring the eastern coast of Santorini and many tiny coves in the two islands in the caldera, looking for a secure anchorage.

“Yes, you can moor here for the night,” says the captain of a large schooner in a cove on the north coast of Nea Kameni , “but if you do you must keep all your hatches closed because the rats will come aboard.”

The islands are infested with the creatures and they have grown quite ferocious.

“Follow me and I will show you a much better place where there are hot springs .”

In half an hour, after following the schooner between two reefs, we are moored in the pass between old and new Kameni. The sun sets. Ashore, a small white church perches on a lava outcrop. Astern, houses spill off Ia, golden in the wan light. The hot springs are in a tiny cove to the east of the church. All day long, a parade of boats have ferried tourists into the tiny harbor to swim in them, but now we are alone. Terry and Kim ascend the cliffs to reconnoiter and take photographs. I keep watch on Asteria. When they return, we will have the springs to ourselves.

At night, lightening licks the horizon to the north. A thick tongue of white cloud slides over the glitter of Ia and Fira to the east. Enclosing arms of lava reach into the sky all around. We lie securely tied to a heavy mooring ball in the center of the caldera. It is quiet and peaceful – one of the most beautiful anchorages on our cruise so far. We are unsure of tomorrow's destination. The weather predication is for north-northwest winds at force 3 to 4 for the next 12 hours. We will decide our route when we clear the shelter of the caldera and find the wind. In the meantime – isolated from the bustle of the world all around – we enjoy this moment of arrested time.

****

Wednesday – September 20

We wake to a satin sea. The sun rises over the eastern rim of the caldera. The village of Potamos , on the island of Nisos Thirasia , glows. We are underweigh by 8 AM , passing Ak. Trypiti, the southern tip of the island. [2] Just before exiting the caldera, we find a grotto that leads from the sheltered waters to the open ocean. I venture to within fifty feet of the opening, Kim snorkeling ahead to clear the way. Terry joins Kim for a recce while I keep Asteria in a close holding pattern.

“Outstanding,” says Terry when he comes aboard, “you can easily see the bottom in 60 feet of water.

Two brightly colored caiques round the point and pass close aboard. We exchange waves. Everyone we have met on this trip has been helpful to us. Perhaps sailing offers entre to a more intimate connection with the people we meet? On land, Santorini is saturated with tourists; yet on the ocean, we are among a handful of sailors. On our passages between the islands we have seen, at most, two other sails on the horizon. I had anticipated that arriving by yacht might distance us from the local people, but the reverse seems to have happened. Now, as we proceed toward Folegandros under power, we are once again totally alone.

Olympia radio predicts northerly winds, force three to four , but the sea all around us is unruffled. We will check out Folegandros and stay if it seems welcoming, otherwise we will continue on to Milos – one of the most important destinations of our trip.

****

“I don't like the Cyclades ,” a man in Vlikadha told us, “It's too barren.”

He's telling the truth to some extent, but the bleak quality of the islands is part of their charm. Stark against a sparkling sea, they rise like contorted sea creatures. Against their drear flanks, the clustered settlements of white houses seem to shimmer. Now, after nine days sailing among the Cyclades , our aesthetics have been stripped of expectations. We are alive to nuance. Groves of stunted trees appear to be luscious oases. We distinguish differences in the muted colors – varying shades of umber, tan, gray; subtle greens; the light shades of blue in shoal waters around steep headlands. We can see an abstract beauty in this landscape, like that of the simplified and stylized Cycladic figures carved almost five thousand years ago by unknown sculptors.

The sea is calm, reflecting back the cliffs of Folegandros as we pass around the island's eastern verge. A puffy cumulus cloud lies over Milos and is reflected in the sea's mirror. We have saved a bucket of precious fresh water from the tanker in Iraklia and we wash our clothes as we motor along Folegandros' lumpy coast. Soon, Asteria's lifelines are festooned with drying laundry.

At three PM , a northwest wind pipes up and we set sail, sliding along at six knots under main and genoa. For a time, Kim and I sleep in the cockpit while Terry keeps watch. We enter an inland sea enclosed by Poliagos, Kimolos and Milos . To starboard, the sheer cliffs of Poliagos are splotched with shades of red, orange and white. Deep ravines spill from the mountain tops. This side of the island appears green with vegetation. The town of Kimolos slides into view, a splash of white houses huddled around a towering cathedral. Kim reads from our guidebook to the Cyclades .

“Listen to this,” he tells us, “There's a city underwater off the coast of Kimolos . Here's what it says: ‘…there was an ancient city in the region of the straight dividing the islet of Ayios Andreas from the main island, more specifically Limni and Ellinika. This city continued to be inhabited in the early Christian period, after which it sank into the sea as a result of a major earthquake. When the sea is calm, the remains of this lost city can be seen at the bottom of the straight.'” [3]

We break out our charts of the area. Ayios Andreas lies off the coast of Kimolos in a large bay which provides a good anchorage. We decide to look for it tomorrow. The sea is now ruffed with white caps. We sail into a bowl formed by the encircling islands. Asteria heels in a freshening breeze.

I open the Greek Waters Pilot and study the approaches to Apollonia – a harbor on the east tip of Milos . Thankfully, we have the option of either anchoring or mooring to a narrow quay. Even now, I am uncertain of my ability to back Asteria into a narrow berth unless the wind is dead calm.

The bells in a tiny blue-domed church at the west end of Apollonia Harbor begin to peel at six-thirty, just after we have finished anchoring. We are in company with four other yachts and a small fleet of traditional Greek fishing caiques. Across the harbor, at the head of the commercial quay, another church gleams in the light of the setting sun. On Kimolos, brightly colored pumice cliffs stand out against unusually verdant hillsides. A newly painted caique – blue hull, yellow trim strakes - passes by on the way to sea. We exchange waves.

“What a beautiful harbor,” says Kim.

Terry goes ashore to check out the “sunken city” at a local dive shop. The dive master Yannis Hakakis knows our old friend Nikos Kartellas. The guide books are accurate, he tells Terry, the city exists in six meters of water and can be dived with snorkel.

****

Thursday – September 21

We maneuver Asteria carefully between the island of Ayios Andreas to port and a steep headland to starboard to enter Ormos Sikia, a large sheltering bay. We had left Apollonia at 8:30 AM , having discussed the dive with Yannis who graciously loaned us masks and fins. When we inquired about the rental fee he replied “den biraze” – “never mind.” With Antares at anchor, we motor in the inflatable dingy over the site of the ancient city, towing Kim who surveys the bottom with mask and snorkel.

“There's a smooth stone here,” he tells us, “and maybe a room.”

Terry and I don mask and snorkel and dive over the side. We swim over clusters of rubble, seeking straight lines which may indicate man-made features on the sea bed. Here and there we find smooth cut stone blocks. The water is so clear that Terry seems to float in space as he ascends from a dive, except for accompanying bubbles of air. I recall the ancient harbor of Kenchreai in Corinth where I spent two months as a diving archeologist with a University of Chicago expedition. After centuries beneath the sea, there was little to distinguish in the litter that was once a thriving seaport of quays and warehouses. Much of it was disorderly piles of rubble from fallen walls. Here it is the same, yet there appear to be alignments of cut stone suggesting rectangular rooms of some sort. We spend two hours diving on the ancient settlement, transported by the sense of a place once thriving and now in ruins.

Ormos Sikia is enclosed by a well tended landscape that is, in the Cyclades at least, remarkably green. Neat stone walls encircle terraces on the hillsides. A row of cedar and a whitewashed wall surround a garden and a traditional house. Above it, on the hill, is a church. Astern of us, a man walks a gently sloping beach, garbage bag in hand, removing debris. We are alone in an anchorage that could accommodate dozens of yachts. The beauty and solitude invite us to linger, but time is waning and Milos lies on the near horizon waiting to be explored. We return to Apollonia, anchor and set out in a rented car to explore.

*****

The ruins of Phylakopi dominate a cliff that overlooks the sea. Tall cyclopean walls thrust into the sky, enclosing a warren of rooms.

“Sam, Look at this,” Terry says, bending over a scatter of tiny black shards of obsidian that litter a trail through the ancient settlement. He holds up a handful of flakes and picks out a tiny fluted core. It is an amazing find, the last remnant of a larger piece that had been struck to flake off obsidian blades. Obsidian is a volcanic glass that breaks evenly and is used to make weapons and cutting tools that ancient sculptors used to carve the famous Cycladic figurines. Archeologists have found that Milos was an important center of the obsidian trade as early as 5500 BC. Trace element analysis has allowed them to identify Melian obsidian at sites in the Greek Mainland, Crete , Egypt and Southern Europe.

Phylakopi first became a thriving settlement during the period 3300-2300 BC. Later, it fell under the influence of the Minoan civilization of Crete . Excavations of the British school revealed a Minoan palace here. The city was burned sometime around 1600 BC (perhaps due to the eruption of Santorini) and later rebuilt with the thick walls that we see all around us. To the north, the walls are composed of rounded boulders smoothed by the ocean like those a few hundred feet away on the shore. Perhaps this is an earlier settlement. The city was finally abandoned in 1100 BC. [4]

Towering cumulus clouds move across the island as we tour Phylakopi. In the late afternoon, as we explore the ruins of a Roman theater below Plaka, mid level clouds blanket the sky. It is dark and dreary. I cannot help but worry about an approaching front that may bring a shift of wind.

Sailors are like turtles. When they leave their boat it's as if they have left their shell behind. Even though we made certain of our anchor, and the wind is calm, I worry about Asteria during our tour of Milos . I cannot fully enjoy myself. I imagine threats to the boat that are almost certainly non-existent. It is one of the few drawbacks of being captain. To some extent we all feel naked without the boat and we find that our most enjoyable moments are spent sailing her and anchoring in secluded coves where we snorkel with her nodding at anchor close by.

*****

Friday – September 22

Kim swims a zigzag path off the bow as we crawl into a small bay underneath the walls of Phylakopi.

“All clear. No rocks. Nice sand bottom,” he yells up to me.

At ten o'clock , after a late start from Apollonia, we are moored. Terry and Kim explore the bay while I stand anchor watch. Terry swims the eastern coast but finds no substance to reports of tumbled walls from Phylakopi. When he returns, I join Kim in a grotto that extends back into a cliff for about 150 feet. Overhead, the rock has been scalloped by the sea. Daggers of stone reach down toward us. The sea floor is smooth white sand and the water is cerulean blue. The cave has two openings. Asteria is framed in one of them.

Returning to Asteria, I find the wind has picked up to about 15 knots, due north. It will be an upwind slog to Siphnos. We raise anchor and proceed under power so Kim can prepare brunch – toast, sausage, fried eggs and bacon. Offshore, we see two yachts under sail, one tacking to windward, the other running down on Milos .

The Cyclades are beautiful, but so is the coast of Maine and the Caribbean . What makes these waters special is the sense of antiquity we associate with the human odyssey all around us. Phoenicians, Egyptians, Mycenaeans, Romans, Athenians have all sailed these routes and ashore they have left traces of their passage. We sail on the same “wine dark sea” they sailed. Following their ancient sea routes arouses in us a deep sense of history.

“Look at those terraces.”

The umber coast of Kimolos slides by as we steer toward Siphnos. Everywhere we see terraced fields girding the island's slopes in neat parallel lines. About two thirds of the way down is a large paddock. A single house, in ruins, adjoins it.

“Where have all the people gone?” Terry asks.

As the smell of bacon rises from the galley, I am aware that we have little time left with Asteria – a day and a half before we must return her to Syros . Kim passes up our brunch. We set the autopilot and enjoy a noon meal together on deck.

“Best restaurant in the Sea of Crete ,” I tell them.

“And with a 360 degree ocean view,” says Kim.

During the afternoon, we report in to Moorings base.

“Where are you headed?” they ask.

“To Siphnos,” we reply.

“There is a storm coming, better go to Serifos because it is closer to the base.”

Entering Livadi harbor on Serifos, we find a large open space at the end of the yacht quay. There is no hope for it. The winds are moderate. I've got to try another Med-moor. Kim brings out the dock lines. Terry readies the anchor. I move Asteria about five boat lengths from the quay and align her with the spot I want. By beginning this far out, I can surely get steerage way.

“Let her go,” I tell Terry.

The chain rattles out as we back down. Asteria minds her helm. Terry modulates the outflow to keep the chain from piling and yet allow free movement. When we are twenty feet from a perfect landing at the pier, Asteria falters, then stops.

“We have reached the end of our chain,” Terry calls back, “We will have to go around and do it again.”

“Just gun her back,” suggests the captain of a boat already moored. “You can drag the anchor. The holding ground is not good.”

Asteria surges under reverse. The anchor chain trembles under the strain. We move toward the pier – twenty feet, ten, five – perfect. The lines go over and we are moored. We exchange high fives all around. I am exhausted and exhilarated. Above us, the chora glistens in the sun. Kim takes pictures.

Serifos has a reputation as a sleepy island but it is surprisingly cosmopolitan. Nowhere else in the Cyclades , except the ruined tourist ports, have we seen gelato stands, internet cafes and trendy bar-discos. Yet here they do not dominate. They blend seamlessly with the more traditional tavernas. At the end of our quay, a few feet from where we are moored, an all white spoon-stern motor yacht draws up. Midnight Sun is a classic design – simple, elegant and understated. She gleams. Stewards serve dinner on her fantail.

*****

Saturday – September 23

“You must see the chora before you go,” says a man carrying a net in Livadi harbor. “It is a most beautiful village. They built it up there because of the pirates who used to raid here in the old days.”

When we dismount the bus in the tiny main square, we find the chora bathed in slanting light. We follow winding paths through the village. Whitewashed walls on each side occasionally open to a view down a steep terraced hill to the harbor. The temperature drops as we climb toward two churches on the Castro. Deep-bellied clouds build to the north and slide over the island. The contrast of bright sunlight and deep cloud shadow adds mystery. No one is about. Doors and windows are closed. The town is eerily silent. We pass a shoe repair shop – a single small room where a man works over his lasts with a tapping hammer. Two men are repairing a house. They unload cement brought up the hill by a donkey. Serifos seems a place I have dreamed. If I blink, it might disappear.

****

Kim toasts a baguette from the Livadi bakery and mixes tuna fish. He passes cheese and sliced tomato up the companionway. We lunch in the cockpit while powering slowly toward Finikas. The wind is on our nose, stirring whitecaps and causing Asteria to plunge as we head back on our last day. Five miles out, we raise main and genoa and kill the engine. We enter the harbor, douse our sails, and moor stern-to as the sun addresses the horizon.

At the end of the pier, I notice a traditional Greek schooner. Her shape is very familiar. She is a perama – schooner rigged, about fifty feet long on deck, with an upthrust beak supporting a bowsprit. Large “fisherman anchors” hang on catheads on each side of her bow. We have all seen a boat like this - Stormy Seas – a schooner owned by Peter Throckmorton, our archeologist mentor. I approach a man who lounges on deck.

“The last time I saw a boat like this, I was with Peter Throckmorton,” I tell him.

“Ah yes, Peter,” he replies. “Will you please come aboard.”

The boat's owner is an affable fifty-seven year old Athenian – Nikos Riginos. [5]

“This boat is modeled after Peter's Stormy Seas ,” he tells me. “I saw her first when I was about 13 years old and I told myself that if I ever had enough money to own a yacht, it would be like his boat.”

Nikos first cast eyes on Stormy Seas in Hydra, where Peter had taken her on his way to an archeological excavation. Nikos was very young but he was already an experienced free diver.

“I met Peter and he invited me aboard. If you are a young boy as I was and if you love diving, it seemed to me that I had met a god. I fell in love with his boat.”

Nikos is a prosperous businessman who helped found Vernicos Yachts, a company that represents Beneteau in Greece and was one of the first bareboat charter outfits in the country. Later, he started a small air freight service of fast courier planes that carried newspapers and fresh fish throughout Greece . He prospered. Twenty years ago, he began to look for a perama. He found Faneromeni [6] in Poros. She was built in Skiathos in 1945 as a cargo boat. After buying her and converting her to a yacht, he researched the boat's history and traveled to meet her five previous owners. On the island of Psara , the boat attracted considerable attention when she tied up at the quay.

“Faneromeni had been the lifeline of the island for twenty years,” Nikos told me, “she carried fruit, vegetables, groceries, all that was needed by the islanders. Many people gathered around. Some of them had crewed on her.”

On a visit to Kalymnos, Nikos met the last man to own the boat – Captain Valas. The captain invited Nikos to his home. A portrait of Faneromeni hung over the mantelpiece. The captain reached up and took it down.

“This is for you,” he said to Nikos.

“He was a simple man,” Nikos said. “He did not have much money. This was his most prized possession. It is due to the magic of this boat that I now have the painting hanging in my home.”

Peter's spirit seemed to be present during this meeting with Nikos as it had often been on our cruise. There was another surprise. During my conversation with Nikos, I told him about my first diving expedition in Greece – at the ancient seaport of Kenchreai.

“Kenchreai?” said Nikos. “Do you remember an archeologist who worked there named Aliki Swift?” [7]

Indeed I did. Alice Swift was one of the young students on the excavation. An attractive out-going woman with a deep love of Greece .

“Well, Aliki married my brother Vasilis,” Nikos told me, “and they are now in our ancestral home on Samos . Shall we phone her?”

The conversation with Aliki is short but heart warming. She now lives in Washington , D.C. and teaches at Howard University . We trade email addresses and I promise to be in touch when we return to the States.

*****

Sunday – September 24

“We've got to plan this carefully,” says Terry, “100 feet underwater is a serious dive.”

It is Sunday and we are waiting aboard Asteria for Nikos Koumarianos [8] to arrive with scuba gear to dive on an ancient shipwreck. Nikos is a very competent diver with sixteen years of experience. He has descended to depths as great as 300 feet with mixed gas equipment. We are both amazed that he would offer us not only an opportunity to dive the wreck, but will provide the boat and all the gear.

“How much will you charge?” we ask.

“I will never take money,” he tells us. “It is my hobby, not my profession. I love to dive.”

Nikos moors his dive boat off a rocky promontory and swears us to secrecy about the location. We don our gear and glide down a steep cliff, floating easily over a field of utter destruction. Thousands of broken amphoras spill into the depths. Sixty feet, ninety, one hundred and ten. Our bottom time is limited at this depth – thirty minutes – with a five minute decompression stop at fifteen feet. All around us lie the remains of the ancient ship. I swim over thousands of broken amphoras - large clay vessels – the cargo containers of their time. Amphoras can be identified by their shapes and especially by stamps impressed into their handles while the clay was wet. The handles of these amphoras arc gracefully from the mouth, terminate sharply, then plunge abruptly back to the body. The shape is distinctive. It is over four decades since I have seen similar amphora, but I recall them vividly. They were made on the island of Rhodes about 2200 years ago.

Terry, Nikos and I fin slowly over the debris field. It seems to cover about a hundred feet of the seabed. The ship obviously struck hard, perhaps caught on a lee shore during a Meltemi like the one we encountered during our first days aboard Asteria. Her bottom was ripped open and she must have capsized to spill her cargo in the wide-spread pattern we observe. I hold up a neck and handle. Terry takes my picture. Then I carefully place the jar where I found it. This is an archeological site and must not be disturbed. Someday, it may be excavated and its clues will reveal the story of sailors who may have perished here.

*****

[1] http://www.therafoundation.org/wallpaintingexhibition/female-figure/wallpainting - virtual tour of paintings.

[2] Chart – Imray Tetra – Southern Cyclades sheet 1 – west.

[3] Cyclades, page 48.

[4] http://www.geoengineer.org/milos.htm

[6] See http://www.sy-thetis.org/Thetis98/Faneromeni/Faneromeni.html - by Nikos brother Vasilis