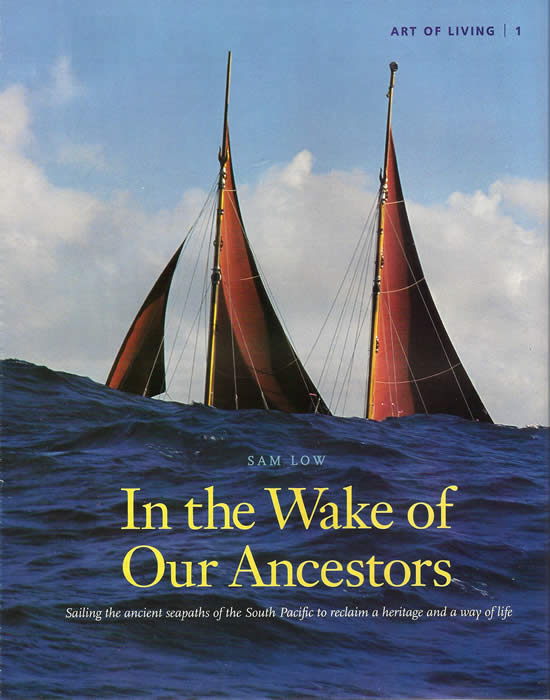

In the Wake of Our Ancestors

Orion Magazine – March/April 2003

All Photos by Sam Low

By Sam Low

“Bring her up.” The command from my navigator is soft-spoken, blending with the sibilant rush of our vessel through deep ocean swells. I am steering by a star just ahead—but the star has risen and arced north. I bring the canoe up into the wind and select another star.

“Good—right there,” comes the command.

We are sailing east seventeen hundred miles across open ocean from Mangareva in the Gambier Islands to Rapa Nui also known as Easter Island. Many have made this voyage before us, but for a thousand years no one has attempted it in the way we do now.

Our vessel is called Hokule‘a (Ho-ku-LAY-ah)—Star of Gladness, after Arcturus, which rises directly over her home in the Hawaiian Islands . She is a replica of the first such craft ever created by Polynesians thousands of years ago: a double-hulled voyaging canoe, what modern sailors would call a catamaran. Hokule‘a's twin hulls, sixty-two feet long, are spanned by a platform seventeen feet wide. She is open to the heavens—a natural observatory.

We sail with no charts or instruments. No timepiece. No compass. We sail as our ancestors did, guided by a world of natural signs—the arcing stars, sun, and moon; the signs of direction in wind and swell; and the mental acuity of our navigator, who employs these subtle clues to ?nd a tiny speck in an immense ocean. Rapa Nui is only thirteen miles wide. We must sail within thirty miles to spot it. If we miss it, the next landfall is South America , two thousand miles beyond.

On September 22, we jump off from Mangareva. For a week, we run under cloudy skies at six, sometimes seven knots. We encounter heavy seas, but our vessel rises easily over them, channeling tons of water cleanly between her hulls. She seems alive, responding to the forces of nature as she was designed to do—a testament to the genius of our ancestors.

As

we make our way east toward Rapa Nui ,

through seas veined with tendrils of spray and scudding storm clouds, I watch

our navigator Nainoa Thompson study the natural world about him for clues to

steer by. I sense that he is willing himself back a thousand years to an era

when Polynesian navigators sailed ancient routes across this same expanse of

ocean. As a compass Nainoa uses the rising and setting points of stars. On this

voyage, for example, Sirius rises at 107 degrees and Aldebaran rises at 74 degrees;

while Vega sets at 309 degrees and Antares at 244 degrees. In the entire menu

of Nainoa's directional stars there are about two hundred. Swells also provide

clues to steer by. Departing Mangareva, we encounter a swell from the southwest.

Generated by a hurricane off the coast of Australia

, it is satisfyingly deep and constant. We set our

course by it during the day and at night when clouds obscure the stars.

As

we make our way east toward Rapa Nui ,

through seas veined with tendrils of spray and scudding storm clouds, I watch

our navigator Nainoa Thompson study the natural world about him for clues to

steer by. I sense that he is willing himself back a thousand years to an era

when Polynesian navigators sailed ancient routes across this same expanse of

ocean. As a compass Nainoa uses the rising and setting points of stars. On this

voyage, for example, Sirius rises at 107 degrees and Aldebaran rises at 74 degrees;

while Vega sets at 309 degrees and Antares at 244 degrees. In the entire menu

of Nainoa's directional stars there are about two hundred. Swells also provide

clues to steer by. Departing Mangareva, we encounter a swell from the southwest.

Generated by a hurricane off the coast of Australia

, it is satisfyingly deep and constant. We set our

course by it during the day and at night when clouds obscure the stars.

To find his latitude, Nainoa observes the meridian crossing (the highest point of rising) of various stars. But it takes a trained eye. A mistake of a single degree in estimating a star's altitude is equivalent to a sixty-mile error on the ocean. To ?nd longitude, Nainoa uses dead reckoning. He estimates daily the course he has sailed and the distance made good.

Thor Heyerdahl once proposed that Polynesia was settled by Indians from South America who drifted from east to west, riding the prevailing winds and currents aboard primitive rafts. We now know this is not true. Anthropologists have discovered the origins of Polynesian culture in Southeast Asia . Linguists have traced the spread of that culture from west to east, across island stepping stones to Fuji and Tonga , and then on into the great Polynesian Triangle. And archeologists have found evidence that the first Polynesians arrived in Fiji about the time the walls of Troy were falling to the Greeks. Contrary to Heyerdahl's thesis, these men were competent sailors and navigators who forced their way against the currents and winds to settle a ten-million-square-mile expanse of ocean. And they did so in vessels much like Hokule‘a.

Nainoa Thompson first sailed aboard Hokule‘a in 1976, on a voyage from Tahiti to Hawai‘i. The experience awakened in him a deep urge to know more about his ancestors. “My grandmother grew up in a time when Hawaiians were beaten in school if they spoke Hawaiian and they were ashamed to be dark skinned. Ever since the arrival of Captain Cook we have been increasingly disconnected from who we are. But when I sailed aboard Hokule‘a it kindled in me something that I only partially understood but felt instinctively—pride in my heritage. I knew that voyaging was an essential part of our ancient culture and I felt that if we could sail in the wake of our ancestors we might begin to understand who we are as Hawaiians.”

Nainoa has since voyaged more than ninety thousand miles aboard Hokule‘a. He has sailed from Hawai‘i, the northern frontier of the great Polynesian Triangle, to New Zealand , the southern frontier. He has sailed to Samoa , the triangle's western reaches. Now, he sails east on the most ambitious voyage of all.

The prevailing winds in this part of the Pacific are the southeast trades, so Rapa Nui lies upwind, seventeen hundred miles ahead. If the winds hold, we will have to tack—extending our voyage to four thousand zigzagging miles. Every mile will be cold and wet, testing our endurance and our discipline. But the real challenge will be finding the tiny island. On all his previous journeys, Nainoa has been able to aim his canoe at a broad chain of islands. Tahiti , for example, is part of a chain that stretches across some four hundred miles of ocean—a kind of navigational safety net. But on this voyage, there is no net. Rapa Nui stands alone.

“I sail there in humility and in respect for my ancestors,” Nainoa told me before setting out, “and to renew the ancient tie of brotherhood between my people, the Hawaiians, and the people of Rapa Nui .” I learned the importance of this part of our mission when I visited Rapa Nui a year earlier in Nainoa's company. As we left to return to Hawai‘i, an elder approached us. “We look forward to the arrival of Hokule‘a,” he tells us, “because she brings with her the promise of helping us to revive our ancient culture and to join together once again all the families of Polynesia .”

For this voyage, Nainoa has chosen his crew of twelve with care. We are what Nainoa likes to call “professionals” in the broad sense of the word—seasoned by life, dedicated to our work and families. Most of us are Hawaiians—a college professor, two longshoremen, a lawyer, an EMT, a doctor, a sailor. All but two of us have voyaged on Hokule‘a before, six are veteran sailors, and two have trained with Nainoa for over a decade.

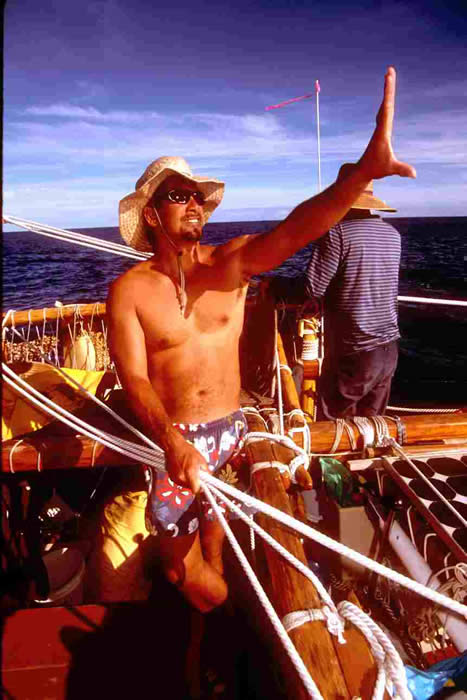

Nainoa (right) observes sunset for signs of tomorrow's weather

As Hokule‘a proceeds east, I observe Nainoa staring hour after hour into what appears to be an empty expanse of sea. “When everything is going right,” he explains, “I get into a zone of concentration in which all of my relations with the canoe, the natural world, and the crew are integrated. I must be in that special place to navigate. When I'm in the zone, I have the star patterns in mind and I seem to know where I am even when the sky is cloudy. I anticipate the weather. It's an awesome feeling.”

Nainoa's training has blended old and new, Western science and traditional learning. He spent hundreds of hours in the planetarium at Honolulu 's Bishop Museum , where he slept under the spinning stars, waking to map their paths in his mind, catnapping, waking again. His teacher, skywatcher Will Kyselka, moved the planetarium's artificial sky across parallels of latitude, replicating voyages throughout the vast Pacific. Then Nainoa went to sea in a tiny sixteen-foot boat to observe the heavens off the friendly shores of Oahu . He traveled throughout the Hawaiian Islands , seeking new vantage points.

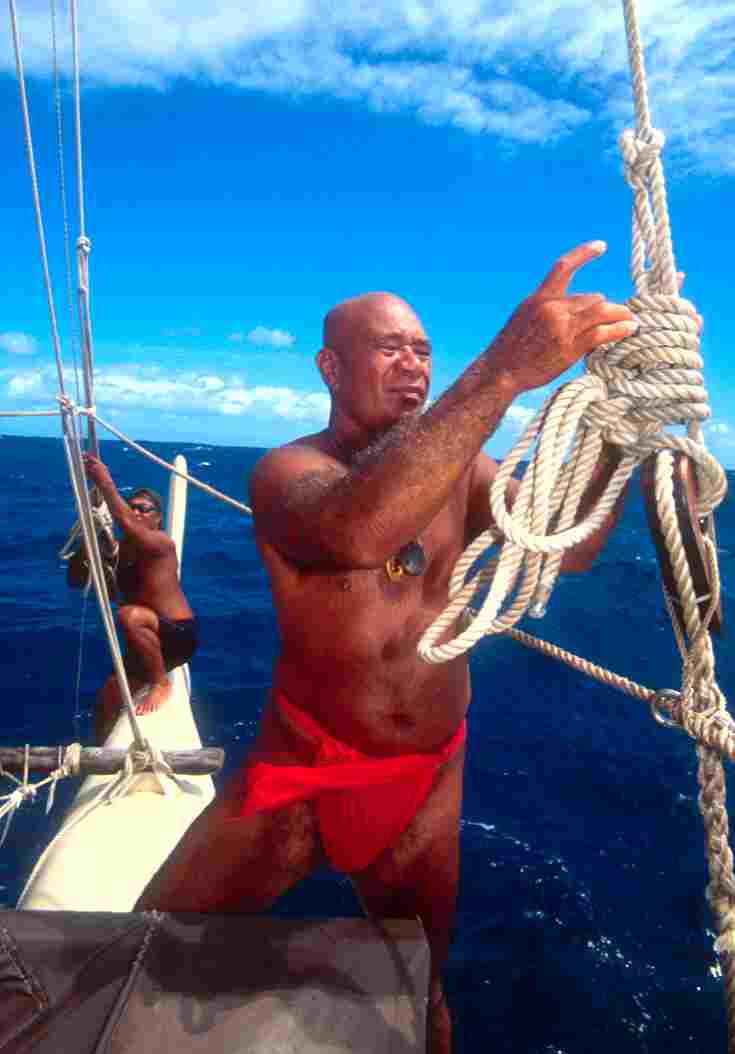

But something was missing—a mentor in the old ways, a master of the ocean. On the tiny Micronesian island of Satawal Nainoa found such a man in Mau Piailug, one of a handful of traditional Pacific navigators who still practices the ancient craft of his ancestors. “Mau took me by the hand as a father would and he taught me slowly and patiently all that he felt I needed to know.”

Nine days out from Mangareva, the sky clears. Jupiter rises ahead—just where the sail blocks the sky, almost due east. On watch, I steer by allowing the planet to appear briefly, then I push the steering paddle down lightly, causing Hokule‘a to turn up into the wind until Jupiter begins to swing behind the sail. Then I drop the blade, Hokule‘a turns down, Jupiter reappears. The polished ball of the paddle curves into my hand. The canoe speaks with pressure against my open palm. Jupiter appears, disappears, then reappears. The stars cascade overhead while the planet rolls toward daylight.

Hokule‘a invites us to a dance attuned to the swells. When we are on course, the swell from the southwest lifts her starboard hull, passes under, then lifts the port hull. We begin to feel our course in the soles of our feet and in the delicate balance point in our middle ear. We attune our hearing to subtle changes in the sound of ocean rushing between Hokule‘a's hulls.

“Listen,” she seems to tell us. “Can you hear it? You are on course!”

We had expected that the southeast trade winds would force us to tack constantly, but so far we have experienced a kind of miracle— the winds have blown from every direction but southeast. They have been strong from the north, west, and south, allowing us to proceed east at speeds sometimes in excess of seven knots. If this keeps up, we will be in the vicinity of Rapa Nui within a week.

On

our eleventh day at sea I observe our Marquesan crew member, Tava Taupu, as he

guides Hokule‘a. Tava grips the immense steering paddle with the assurance of

thousands of miles of voyaging. Time passes—half an hour, an hour. Crew member

Mel Paoa steps up behind Tava. He stands there for a few minutes, silent, feeling

Hokule‘a's motion, adjusting his rhythms to hers. Then he gently reaches forward

and lays his hand on Tava's shoulder. Without a word Tava steps aside, allowing

Mel to take the paddle. Changing the watch. How many times through the eons

has such a passage of responsibility occurred? As we dance together into our

shared past, we become, as one crew member put it, “the family of the canoe,”

inspired to a deep sense of community.

On

our eleventh day at sea I observe our Marquesan crew member, Tava Taupu, as he

guides Hokule‘a. Tava grips the immense steering paddle with the assurance of

thousands of miles of voyaging. Time passes—half an hour, an hour. Crew member

Mel Paoa steps up behind Tava. He stands there for a few minutes, silent, feeling

Hokule‘a's motion, adjusting his rhythms to hers. Then he gently reaches forward

and lays his hand on Tava's shoulder. Without a word Tava steps aside, allowing

Mel to take the paddle. Changing the watch. How many times through the eons

has such a passage of responsibility occurred? As we dance together into our

shared past, we become, as one crew member put it, “the family of the canoe,”

inspired to a deep sense of community.

The family of this canoe extends well beyond Hokule‘a's decks. By satellite phone, I am sending reports back to Hawai‘i where they are posted daily on the internet site of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, our sponsoring organization. Three times each day our navigators speak directly with classrooms throughout Hawai‘i where children of all ages and nationalities follow us as we proceed east. Island newspapers, even mainland ones, carry reports of our progress.

“This voyage is not about us,” Mike Tongg from Oahu told me during one of our watches together. “It's about our ancestors, about rediscovering our pride as a great seafaring people and about sharing that pride with as many people as possible.”

“When I grew up in Hawai‘i,” says navigator Chad Baybayan, “It wasn't really cool to be Hawaiian. We had lost our heritage. When I saw Hokule‘a for the first time, I knew that I wanted to sail aboard her. She would be one way to recapture our ancient knowledge—our ancient pride of heritage—and carry that message far and wide.”

Perhaps two words, both of them integral to the vision of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, best express this goal. ‘Imi ‘ike means “to seek knowledge” and lokomaika‘i means “to share with each other.” During the last quarter century, the Society has married each voyage with an appropriate educational program to present the achievements of the ancient Polynesians to all the children of Hawai‘i.

In 2001 Nainoa and the Voyaging Society founded The Ocean Learning Academy, a two-year charter school program for high school students that focuses on Hawai‘i's cultural, social, and natural environments. Ocean Learning students sail aboard Hokule‘a. They study the weather in preparation for their voyages and learn about navigation by the stars. They monitor populations of reef fish and map coastal environments alongside scientists from the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology . “They learn by doing,” as Nainoa expresses it, “by collaborating with each other and with their teachers as we do aboard Hokule‘a.”

October 6, our fourteenth day at sea. Sailing under an immense dome of sky, we are surrounded now by a horizon populated only by clouds and stars. “When you voyage,” Nainoa says, “you begin to see the canoe as a tiny island surrounded by the sea. We have everything aboard the canoe that we need to survive as long as we marshal our resources well.”

Navigator Bruce Blankenfeld uses his hand to

judge the altitude of the sun

Our ancestors fashioned seagoing canoes with stone tools. They used koa wood for the hulls, breadfruit sap and coconut husks for caulking, and coconut fiber rope for lashings. “When our ancestors went to the mountains to cut down trees they did not think they were taking the tree's life,” crew member Bruce Blankenfeld once told me. “They were just altering its essence, taking it from the forest and putting it into the sea, and in Hawai‘i the sea and the land are tied together. Everything in the sea has a counterpart on the land because on an island the land and the sea rely on each other for life.”

Sailing the ancient starpaths has inspired among Hokule‘a's crew members a new way of seeing their world. Nainoa calls it wayfinding “Our ancestors began all of their voyages with a vision,” he explains. “They could see another island over the horizon and they set out to find these islands, eventually moving from one island stepping stone to another across a space that is larger than all of the countries of Europe combined.”

“After many years, I began to understand that wayfinding was really a model for living,” he continues. “Once you have the vision of land over the horizon, you must plan how to get there. You must evaluate the skills you need to carry out your plan and then you must get those skills. Then, when you leave land, you must have a cohesive crew, a team, and that requires aloha, a deep respect for each other. Vision to see islands, the ability to plan the voyage, the discipline to train physically and mentally, the courage to take risks, and a deep sense of aloha to bind the crew together during the voyage. These are Hawaiian values, but they are also universal values. They worked in the past and they will work today.”

On the seventeenth day, the winds blow strong from the northeast. Nainoa knows we are approaching Rapa Nui , but clouds have obscured the sky for three days, so he's navigating by dead reckoning from his last latitude. At dawn on the eighteenth day, lookouts are posted.

Max points out Rapa Nui to crew member Aaron Young

As the rising sun paints the sea crimson, Max Yarawamai spots two holes in the clouds ahead, low on the horizon. Born and raised on the low Micronesian atoll of Ulithi, Max's ability to see islands at great distance is legend aboard Hokule‘a.

“I looked carefully at the two holes in the clouds low on the horizon,” Max explained later, “checking first the one on the starboard side. I saw nothing there so I switched to the hole on the port. I saw a hard, flat surface there and I watched it carefully. Was it an island? The shape didn't change! We had found the dot in the ocean.”

With this landfall, the easternmost point of the vast Polynesian Triangle, Hokule‘a has achieved the mission envisioned for her when she was launched more than twenty-five years ago. She has proved the seagoing ability of craft like her and confirmed the genius of ancient Polynesian navigators. But she has also carried her crew and all those who have taken her into their hearts toward a coherent new way of seeing their world.

“When we sail we find ourselves surrounded by an empty ocean which forces us to turn inward and consider how to take care of ourselves, each other, our canoe,” Nainoa says. “Learning to survive on long voyages also forces us to consider how to survive on the islands we live on. In Hawai‘i we are surrounded by the world's largest ocean, but I see Earth itself as a kind of island, surrounded by an ocean of space. In the end, every single one of us—no matter what our ethnic background or nationality—is native to this planet. As the native community of Earth we should all aspire to live in pono—in balance—between all people, all living things , and the resources of our planet.”

*************************