HARTHAVEN ARTISTS - ABBE, LOW, PRIZER

At Featherstone Center for the Arts

July 22 - August 8, 2018

Bill Abbe

Douglas Prizer

Sanford Low

Harthaven Artists Abbe, Low, Prizer

by Sam Low

Harthaven - The Founder

According to family lore it was the spring of 1911 when William H Hart, summer resident of Oak Bluffs (then Cottage City) for forty years and president of Stanley Works in New Britain, Connecticut (maker of those famous tools) walked a stretch of beach to the east of Farm Pond. Standing on the beach, he faced open ocean all the way to Spain. Turning around, he saw a marsh and beyond that farmland. The property was for sale. The marsh could be dredged, he thought, to create an ample harbor with piers and boats and houses overlooking them. Further inland he imagined a grand summer home, all white, with columns at the entrance and a lawn in front. He would divide the farmland into lots and sell them to family and friends. He would create a new community here and he would call it Harthaven.

The first houses built in Harthaven were those of Mr. Hart’s five sons and one daughter. Over time, other relatives and friends moved in, uniting the community by ties of kin and propinquity. Children were allowed to run free because the entire community watched over them. William’s son, Jim Hart, purchased a half dozen small sailboats and held sailing classes and races over which he presided with a booming voice amplified by a megaphone.

“He was firm with us. He taught us how to sail but he made it a lot of fun” Phronsie Conlin recalls. “The first prize was twenty-five cents, second was fifteen cents and third was ten cents. He had his megaphone. He’d shout, ‘Pull in your sheet!’ ‘Tack!’ ‘Watch it - you’re going to gybe!’ We loved it and we loved him.”

I grew up in Harthaven. As a child I spent every day at the communities’ harbor or beach with a gaggle of other children where we learned to swim, row, sail, dig clams and catch crabs. I remember returning to Harthaven from fishing expeditions with my father, Sandy Low, in his Jersey Sea Skiff. Turning toward our pier, I saw my grandfather standing in front of his house. He held up his hands, palms upward: "How many fish?" We held up the requisite number of fingers.

We tied to a dock owned by an uncle - Stan Hart - who kept his boat on the opposite side of the pier. They were, over the years, mostly Erford Burt boats - carvel planked with smooth hulls that rose to the bow with graceful sheer. Each one bore the name of a sea bird - Curlew, Kittiwake, Mollyhawk.

We cleaned our fish on a table nailed to pilings. My father taught me to lay the knife flat along the ribs and slice smoothly, feeling for the bones, leaving little behind. Fish heads and carcasses accumulated in the harbor's clear water, attracting blue claw crabs. I would net them for dinner. At night, the carcasses attracted eels and we speared them in the beam of a flashlight.

For adults there was the constant round of cocktail parties, fishing expeditions, and the annual clambake that drew them close. There was so much to do within the confines of the community that Harthavenites tended to be a little insular, which others sometimes mistook for snobbery.

“Harthaven was not stuffy,” wrote my cousin, H. Stanley Hart, in a years-ago Gazette memoir. “The older crowd seemed to exude a way of life that was abundant in humor and action and a style that flowed from a Yankee heritage. They were as normal as an August nor’easter or the herring run that fed through Harthaven into Farm Pond in Oak Bluffs.”

While the pleasures of boats and the sea were central to the spirit of this remarkable place, Harthaven also drew a rather bohemian crowd of artists who enlivened the community of Yankee businessmen and entrepreneurs.

Harthaven - The Artists

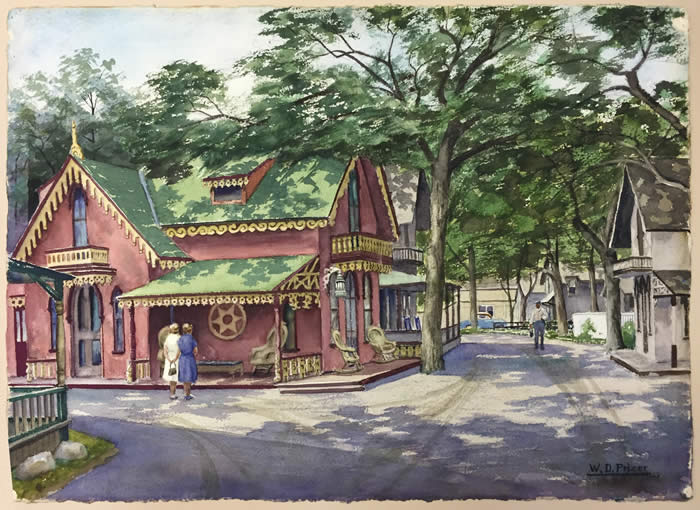

Every year, my father, Sandy Low, convened his “artists group” to paint for a week. I remember them gathering in the early morning smelling of cigars, garlicky food and often, liquor and fish. By seven or so, they were gone to paint all over the island. They came back with scenes of beaches, boats, houses, lobster pots, gulls, fishermen. At the end of their stay, they displayed their work on the porch of my parents’ “Gingerbread House” which they moved to Harthaven from the Campgrounds in 1938. Everyone came to drink gin and tonics and “Old Fashioneds” and admire the paintings.

Down the road a bit was Bill Abbe’s house and studio which looked out over Farm Pond and the ocean. “He painted every day,” remembers his great-nephew Dakkan Abbe. “He always had at least one large canvas on his easel. There were newspaper clippings, magazine articles, art books open, and always, always, some small toy hanging from the ceiling by a slinky coil that would make it bounce up and down.” Bill’s home was as an impromptu gallery where his art adorned almost every wall. “They had parties and everyone came including, of course, the artists,” says his niece Carol Abbe. “The house was filled with song – ragtime and songbook stuff.”

And high on a bluff overlooking Harthaven’s beach, Doug Prizer’s home faced the open ocean. “He set up his studio in the screened-in porch that looked out to the southeast with a sweeping view of the beach curving to Chappaquiddick,” his grandson, Paul Prizer remembers. Doug was well known for his cocktail parties, which attracted many of his neighbors, and he enjoyed the company of the other Harthaven artists. “Doug and Bill Abbe traded ideas and discussed their paintings with each other. Doug painted a portrait of me when I was five and it hangs on my wall today,” says Dakkan Abbe.

Abbe, Low and Prizer were the most active of Harthaven artist but there were many others, some who created for personal pleasure, some for a livelihood. Among them were Grace Vibberts, Nelson Augustus Moore, Louis Fusari, Martha Pease, my mother Virginia Low and Mary Stevens whose family sold the land in 1996 for what today has become the Featherstone Center for the Arts. Perhaps it was coincidental that so many artists were nurtured in Harthaven, but I think they were drawn by the deep sense of community and the presence of so many other creative people.

“Artists are attracted to places that are beautiful and that nurture them,” says Bill Abbe’s nephew, Dakkan Abbe, “the Harthaven community loved their artists, buying paintings from them and attending their exhibitions.”

Bill’s Abbe’s early work, created in New York, shows gritty street scenes - construction sites, tenements, store fronts - often rendered in black and white block prints or charcoal drawings and often somewhat cartoonish. On Martha’s Vineyard, he loved to paint the colorful filigree of Camp Ground houses or the flash of white sails in a regatta off Edgartown. One of my favorite block prints is his depiction of the “On Time” - the Chappaquiddick Ferry - when it was pressed into service to bring passengers and cars from Falmouth during the eleven-week-long steamship strike of 1960. Bill developed a signature, highly graphic and geometrically abstracted style. Sails, campground curlicues, architectural elements are shown from many perspectives, collided, and sometimes presented in a time lapse sequence to render motion. And color – a playful riot of joyful in-your-face color. He so loved to experiment, to play with his art, that he is difficult to categorize.

Early in his career, Sandy Low painted murals in oil for restaurants, banks or public buildings. But he later mastered watercolor painting, the delicate art of washing the paper and applying a flow of color on the moist surface to produce, for example, a seamless yet nuanced sky or sea. He delighted in a slightly askew perspective - telephone poles and houses often lean away from each other and he used color to evoke mood, a light wash of blue sky over a leaning farmhouse suggests fading memory, a dark wash of blue-green sky over houses perched on a dark cliff suggests permanence.

I once asked him why he always painted sorry-looking dilapidated buildings. “Why don’t you paint a new one?”

“Because old places are more beautiful,” he told me, “they contain the memories of all the people who lived in them.”

His paintings were mostly representational, sometimes almost photographic, but he loved to experiment. Perhaps following Picasso’s dictum, “A good artist never copies, he steals,” he deployed Pollack’s drip style to create abstract yet still realistic paintings - as in “The Cocktail Party” - or he used a pallet knife to suggest motion and emotion as in his painting of seagulls thrashing the ocean in a feeding frenzy.

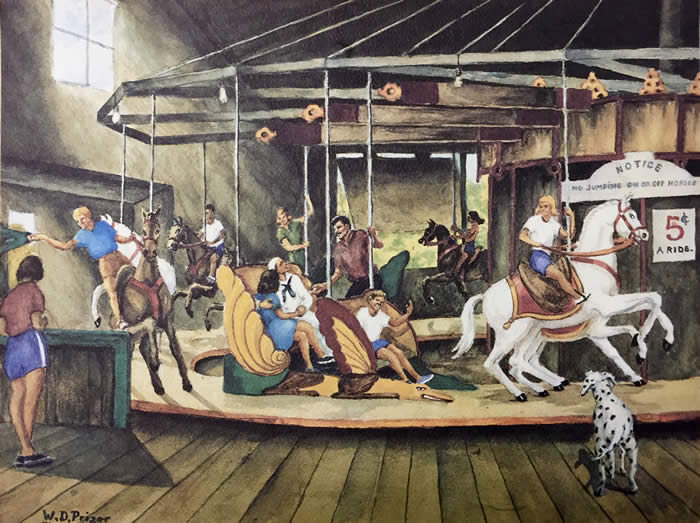

Doug Prizer loved to include people in his work, delighting in their social interaction, telling island stories. In “Flying Horses,” the attendant converses with a sailor and his girl, a young man reaches for the golden ring, a woman waves to someone, a spotted dog focuses on his owner flying by. He loved color and used it to convey his own impressions rather than always render them accurately and he often laid his colors on the paper thickly instead of washing them. He captured rhythms in the play of shadows and the way his trees reached to the sky.

“He did not paint abstractly,” says Paul Prizer, “but he was a little impressionistic. He told me that the values of light are more important than the color you use. ’You can paint a face green and no-one will care as long as the light values are correct and the lighting looks correct,’ he said. He was very liberal with his color palette.”

Martha’s Vineyard is remarkable for the artists who are attracted here but also for the intimate neighborhoods, like Harthaven, in which they – and we – are nurtured. Think of the Campgrounds, East Chop, West Chop, Sepiessa and The Highlands, to name just a few. If we are lucky enough to grow up in such places, we become part of a ribbon of history. We become part of, as Wendell Berry wrote: "the kind of knowing that involves the senses, the memory, the history of a family...” Or, as he wrote in his poem, “In Rain:”

I walk this ground

of which dead men

and women I have loved

are part, as they

are part of me.

The Art

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Exhibit

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|