IT FREED HIS HEART

Tomas Hart Benton and Martha's Vineyard

By Sam low

Martha's Vineyard Magazine – July 2004

I first met Tom Benton one evening when he came to spend the night with my parents. My first impression was of a sturdy rumpled man with an expressive face who moved about with authority accompanied by the aroma of cigars. The next morning, after my parents and Benton had spent a long somewhat bawdy evening together, I went into my bedroom where Benton had spent the night. I found a Latin dictionary on the bed stand. I was impressed because my own struggles with Latin were not going well and I couldn't imagine an adult – a famous artist to boot – subjecting himself to such torture. I quickly learned that Tom Benton was not your typical adult. His quest for learning continued all his life.

Born in the spring of 1889, Benton began painting when he was very young and he completed his first self-portrait when he was sixteen. He studied in Chicago and then in Paris from 1907 to 1911. Like all young artists, his early work imitated the style of the day – cubism and impressionism – but he was never satisfied. He wanted to develop his own compositional structure and style – his own statement. “Because of my revolt against the patterns of the schools,” he would write later in his autobiography, “I spent fifteen years on my beam-end, rocked by every wave that came along. I floundered without a compass in every direction.” It wasn't until 1920 when he began to spend summers on Martha's Vineyard , insulated from prevailing artistic fashion and the rarified world of art criticism, that Benton began to find himself.

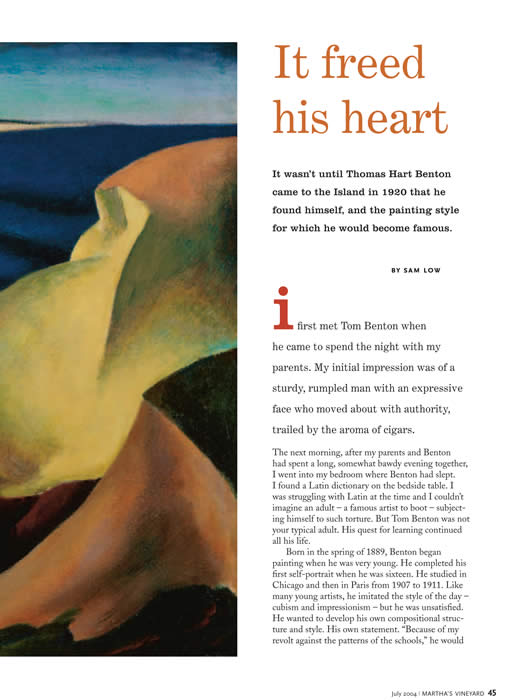

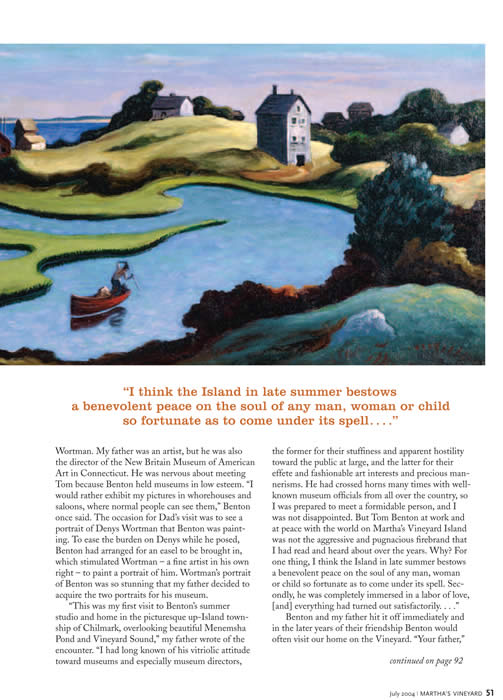

The rhythms of the landscape in Chilmark, deposited by mile high glaciers and sculpted by nature for ten thousand years, inspired Tom Benton in ways that the streets of New York , Chicago and Paris never did. As his island biographer Polly Burroughs put it: “…the beautiful undulating grey stone walls snaking over the hills and reaching down to touch the sea; the bright green marsh grasses skirting the tidal ponds that swayed in the prevailing southwest winds; the contorted twisted vines of the trumpet vine, and the gnarled trunks of the scrub oak inspired him in a manner he hadn't experienced before.”

In his first summers on the Vineyard, Benton completed, among other paintings, Beetlebung Corner (1922); The Cliffs (1921) and Waves (1920). These were landscapes, devoid of human beings, and they explored his passion for color and composition, as he responded to the natural landforms all around him. But while his technique and style matured, Benton felt that something was missing. Still preoccupied by artistic conventions of his day, he had yet to strike off in a new and original direction. In his autobiography, Benton write that the evolution of his art moved through three stages:

“The first is devoted to a search for method. In the second phase the method is developed and its formal and representational potentialities are explored. In the third, the developed method is applied to the expression of those human meanings that the artist's life provide. The first two phases are primarily technical, the last largely communicative.” In the beginning, it was as if the right side of his brain – the intellectual, logical side - was engaged, but the left side – the emotional and instinctual - was not. It was on the Vineyard that the two aspects of his art finally joined to spark a complete and full artistic realization – as well as a more complete and full human being.

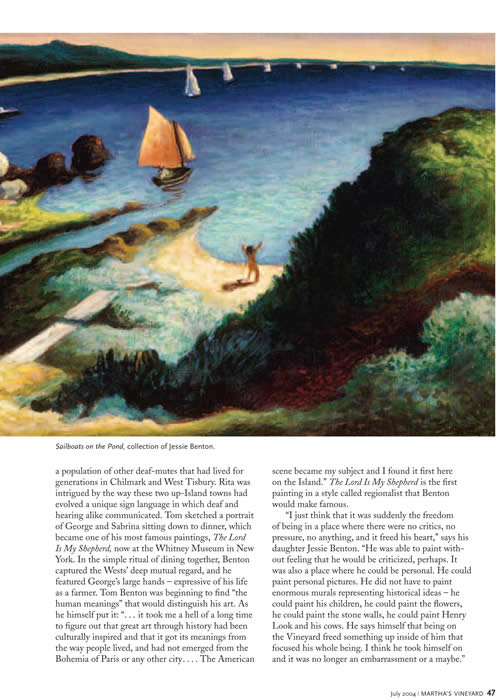

In the summer of 1922, Tom's wife Rita led him down South Road and into the home of Sabrina and George West, deaf-mutes who were descended from a population of other deaf-mutes who had lived for generations in Chilmark and West Tisbury . Rita was intrigued by the way these two up-island towns had evolved a unique sing language in which deaf and hearing alike communicated. Tom sketched a portrait of the couple sitting down to dinner which became one of his most famous paintings, The Lord is My Shepherd , now at the Whitney Museum in New York . In the simple ritual of dining together Benton captured the Wests' deep regard for each other. He featured George's large hands prominently – expressive of his life as a farmer. Tom Benton was beginning to find “the human meanings” that he would express all his life. As he himself put it, “…it took me a hell of a long time to figure out that great art through history had been culturally inspired and that it got its meanings from the way people lived, and had not emerged from the Bohemia of Paris or any other city. …The American scene became my subject and I found it first here on the Island .” The Lord is My Shepherd is the first painting in a style called regionalist that Benton would make famous.

“I just think that it was suddenly the freedom of being in a place where there were no critics, no pressure, no anything and it freed his heart,” says his daughter Jessie Benton. “He was able to paint without feeling that he would be criticized perhaps. It was also a place where he could be personal. He could paint personal pictures. He did not have to paint enormous murals representing historical ideas- he could paint his children, he could paint the flowers, he could paint the stone walls, he could paint Henry Look and his cows. He says himself that being on the Vineyard freed something up inside of him that focused his whole being. I think he took himself on and it was no longer an embarrassment or a maybe.”

Benton was inspired by the human stories all around him. “When the old boys talked, you didn't interrupt them,” Benton wrote of this time, “You let your own concerns go and listened. …You learned things about people who had been on whaling ships and had swum miles at sea holding onto their boots, who had walked across miles of Arctic ice and had their teeth pulled by the village blacksmith with all the local heavyweights sitting on their arms and legs. Listening, you shared not only the adventures, but the spirits of the talkers. Keeping your mouth shut, you came to know the Island folks and what they and the island stood for. You got in touch with what was real.”

The up-Island world that Benton and his family inhabited was peopled not only by year round Vinyarders but also by a freewheeling community of artists and intellectuals. It was a place where folks swam naked, drank freely, and discussed what was happening in the world. “One of Franklin Roosevelt's advisors lived right here in Menemsha,” says Jesse Benton, “Leo Huberman was a famous socialist writer and reformer. They would come to our house and they would all talk. Daddy and Jimmy Cagney used to fight about politics. He was a Republican, Cagney – so they used to fight about politics but that did not mean they could not dance and drink and have dinner together. The head of the American Communist Party was one of our close neighbors. A friend of daddy's. A friend of everybody's. It was a personal place. They all communicated with each other. It was a race of people that just aren't here anymore. They were all individuals. They had contributed a great deal to society – to the ideas of the new world. They had fought Hitler. They were amazing people.”

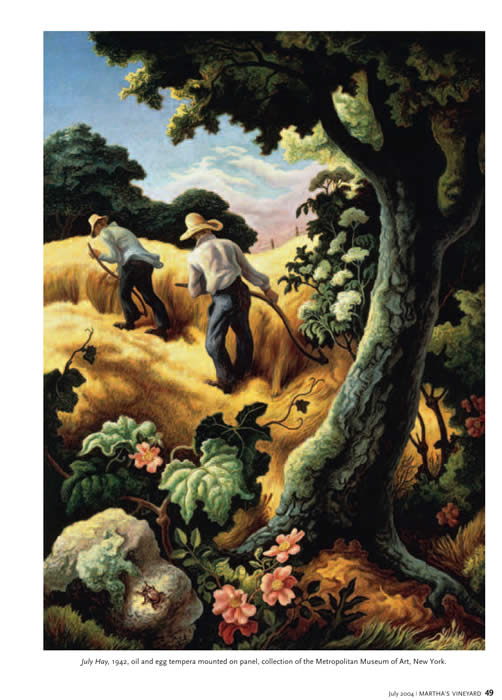

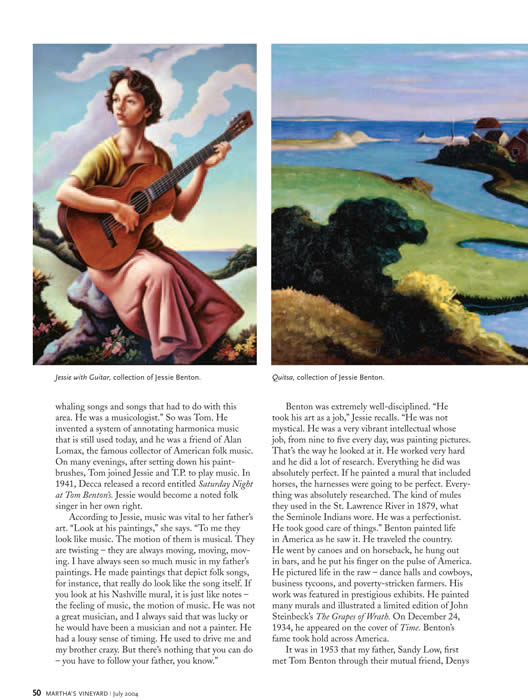

In 1938, the Great New England Hurricane raked the island, destroying the fishing village of Menemsha , and Benton captured a terrible moment in his painting The Flight of the Theilens whose cottage on South Beach was swept away. He painted Henry Look unhitching his horse, farmers haying in July and island folksinger Gale Huntington teaching his daughter to play guitar.

“The Huntingtons were incredible musicians,” Jessie remembers. “They were local people who lived in Chilmark. Gale was a collector of all the whaling songs and songs that had to do with this area. He was a musicologist.” So was Tom. He invented a system of annotating harmonica music that is still used today and he was a friend of Alan Lomax, the famous collector of American folk music. Tom, Jessie and her brother T.P. played music on many evenings after Tom had set down his paintbrushes. In 1922, DECCA released a record entitled Saturday Night at Tom Bentons . Later, Jessie would become a noted folksinger in her own right.

According to Jessie, music played a vital part in her father's art. “Look at his paintings,” she says, “to me they look like music. The motion of them is musical. They are twisting – they are always moving, moving, moving. I have always seen so much music in my father's paintings. He made paintings that depict folksongs, for instance, that really do look like the song itself. If you look at his Nashville mural it is just like notes – the feeling of music, the motion of music. He was not a great musician and I always said that was lucky or he would have been a musician and not a painter. He had a lousy sense of timing. He used to drive me and my brother crazy. But there's nothing that you can do – you have to follow your father, you know.”

Benton was extremely well disciplined. “He took his art as a job,” Jessie recalls. “He was not mystical. He was a very vibrant intellectual whose job, from 9 to 5 every day, was painting pictures. That is the way he looked at it. He worked very hard and he did a lot of research. Everything he did was absolutely perfect. If he did a mural that included horses, the harnesses were going to be perfect. Everything was absolutely researched. The kind of mules they used in the St. Lawrence River in 1879, what the Seminole Indians wore. He was a perfectionist. He took good care of things.” Benton painted life in America as he saw it. He traveled the country. He went on canoes and horses, he hung out in bars, and he put his finger on the pulse of America . He pictured life in the raw - dance halls and cowboys, business tycoons and poverty stricken farmers. His work was featured in prestigious exhibits. He painted many murals and illustrated a limited edition of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath . On December 24 th , 1934 , he appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Benton 's fame took hold across America .

It was in 1953 that my father, Sandy Low, first met Tom Benton through their mutual friend Denys Wortman. My father was an artist but he was also the director of the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut and he was a little nervous about meeting Tom because Benton held museums in very low esteem having once said: “I would rather exhibit my pictures in whorehouses and saloons, where normal people can see them.” The occasion for Dad's visit was to see a portrait of Denys Wortman that Benton was painting. To ease the burden on Denys while he posed, Benton had arranged for an easel to be brought in and stimulated Wortman – a fine artist in his own right - to paint a portrait of him. Wortman's painting of Benton was so stunning that my father decided to acquire the two portraits for his museum.

“This was my first visit to Benton 's summer studio and home in the picturesque up-island township of Chilmark , overlooking beautiful Menemsha Pond and Vineyard Sound,” my father wrote of the encounter. “I had long known of his vitriolic attitude toward museums and especially museum directors, the former for their stuffiness and apparent hostility toward the public at large, and the latter for their effete and fashionable art interests and precious mannerisms. He had crossed horns many times with well known museum officials from all over the country, so I was prepared to meet a formidable person, and I was not disappointed. But Tom Benton at work and at peace with the world on Martha's Vineyard Island , was not the aggressive and pugnacious firebrand that I had read and heard about over the years. Why? For one thing, I think the island in late summer bestows a benevolent peace on the soul of any man, woman or child so fortunate as to come under its spell. Secondly, he was completely immersed in a labor of love, everything had turned out satisfactorily.”

Benton and my father hit it off immediately and in the later years of their friendship he would often visit our home on the Vineyard. “Your father,” I remember Benton telling me, ”is the damndest museum director I have ever known. For one thing, he's an artist himself. He's also a person who knows about art and art history. He's got a good eye. And he likes bourbon almost as much as I do.”

sketch of Tom Benton by Sandy Low

The art word is notoriously fickle. In 1953, Benton 's art was out of vogue. “They took his paintings off the walls of just about every museum in the country,” Jessie remembers. “Daddy was no longer fashionable. Representational art – what they considered American representational regional art - was no longer popular and they literally got rid of it.” One of the museums that was ridding itself of Tom's paintings was the Whitney in New York . Up for grabs were a series of five murals called The arts of Life in America . Benton was, my father thought, “one of the truly great American artists of this century,” and he decided to acquire these murals. The asking price was $500.00, which the museum gladly paid, and they are now the center piece of an entire wing, along with all of Benton 's lithographs which he donated to the museum. And sure enough, as my father had predicted, the pendulum of artistic taste swung back in Benton 's direction. In 1989, an 85 painting retrospective of Benton 's work opened in Kansas City and went on to museums in Detroit , New York and Los Angeles . The centerpiece of the show, on loan from the New Britain Museum of American Art, was the Arts of Life in America murals. Today the murals once again hang on the Whitney's walls in a temporary exhibit – through January 2, 2005 – hailed as a “landmark homecoming” or, as the New York Times called the sale to my father's museum, “a landmark blunder.” The value of the paintings, according to the story, would now be a minimum of $10 million. Today, Tom Benton's place among the best of American artists is secure.

Looking back on the Vineyard world that my father and Tom Benton grew up in it seems a magic place. It was a time before the deluge of the glitterati and the fabulously wealthy – a time when Martha's Vineyard seemed truly remote. The Bentons were poor but that did not matter to the hard working folks who inhabited the island. “They liked him, Jessie remembers. “He was appreciated for being an artist even though he was kind of different. In those days money had nothing to do with it. Your standing came from who you were and what you did and what kind of a person you were. It was a place where you can make a drawing of old Ernest Flanders and he will give you a couple of lobsters. My mother was a fabulous bread maker and she would trade with the locals for whatever they needed. That was the way that we lived here. Everybody knew everybody. I could walk from house to house. It is hard for anyone today to imagine what that world was like. There was a feeling of camaraderie. We were all safe with one another because we were all on the vineyard. It did not have anything to do with background or money or who you were or how you were raised. It was as if the Vineyard itself was your calling card. It was very beautiful.”

Benton Paintings courtesy of Jessie Benton.

As it appeared in the magazine