Aloha and welcome to a page dedicated to

the Mo'olelo of Hokule'a

"When we voyage, we open doors to perceptions we did not previously know existed. We meet new challenges, form new relationships and discover new visions of our world. Hokule’a’s mo’olelo - her shared stories - are the foundation for our continuing exploration."

Nainoa Thompson

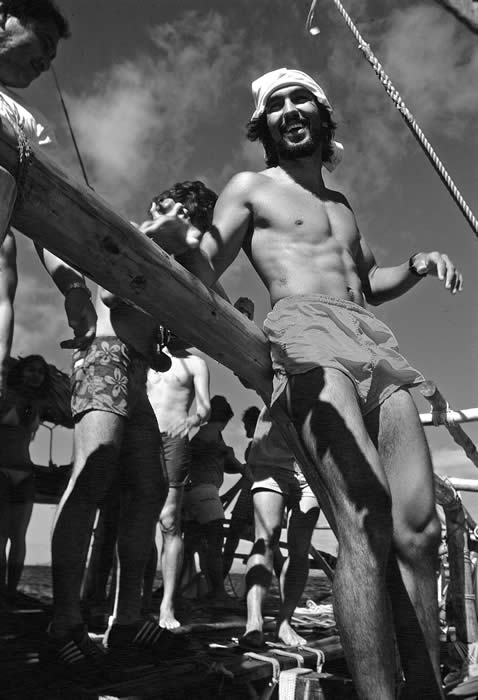

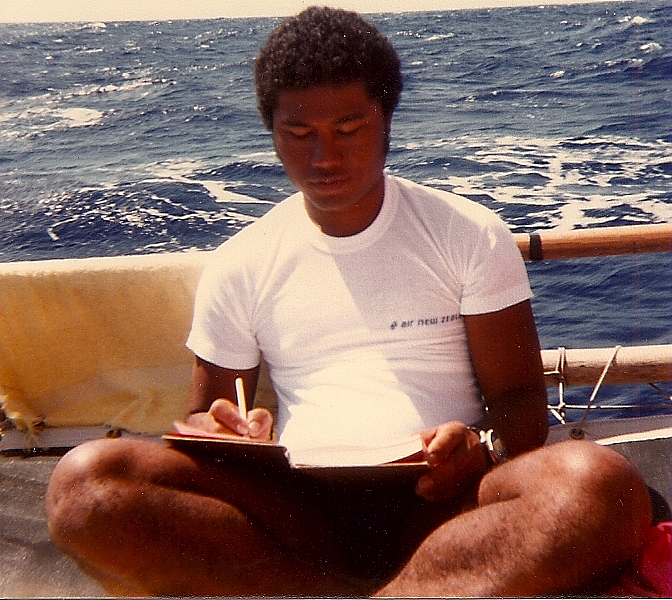

Nainoa Thompson c. age 20

Finding My Way

Nainoa Thompson

Becoming a Crew Member for the First Voyage to Tahiti

It was the first year I was paddling for the Hui Nalu Canoe Club, and I happened to be at the right place at the right time. Herb Kane was living across the canal from the club at Maunalua Bay. It was 1974, and Herb, Tommy Holmes, and Ben Finney were designing Hokule’a. The canoe hadn't been built yet, but they had a smaller canoe then, and they'd ask us to paddle it out of the canal over the reef into the open ocean. That was great! I was at the club every day so I could paddle the canoe out.

Then one day, Herb invited two of the paddling coaches and me over to his house. Herb's house was filled with paintings and pictures of canoes, nautical charts, star charts, and books everywhere, interesting books! Over dinner Herb told us how they were going to build a canoe and sail it 2,500 miles without instruments-the old way. "We're going to follow the stars, and the canoe is going to be called after that star," Herb said, pointing to the star Hokule’a (Arcturus). This voyage would help to show that the Polynesians came here by sailing and navigating their canoes-not just happening to drift here on ocean currents or driven by winds. The voyage would do something very important for the Hawaiian people and for the rest of the world.

In that moment, all the parts connected in me that had seemed unconnected in my life. I was twenty and looking for something challenging and meaningful to do with my life. I had a hard time finding that inside the four walls of a classroom. Here it was-the history, the heritage, the stars, the ocean, and the dream... there was so much relevance in that dream. I wanted to follow Herb; I wanted to be part of that dream.

Herb told us what the requirements would be to sail to Tahiti. We would have to go through a training program in which we would learn all about the canoe and how to sail her, and there would be physical training and training in teamwork. They would select the best 30 from the several hundred who participated in training.

When Hokule’a was completed in the spring of 1975, I participated in the training and was assigned to the return crew. If I want to do something, I can be very disciplined. My dream was coming true.

Taking Hold of the Old Story

Sam Ka'ai

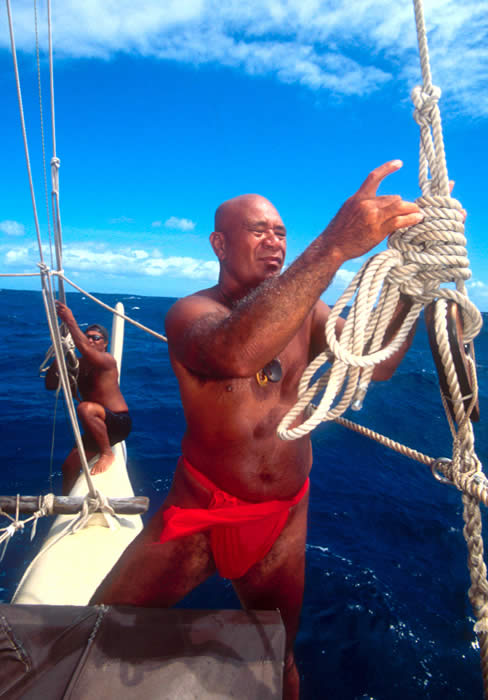

Sam Ka'ai 1997

Sam Ka’ai was brought up in Kaupo, an old district of Hawaiian homesteads in rural East Maui. Until 1938, there was no road to Kaupo. When they finally put one in, Sam’s father and stepfather worked on it. His family raised pigs and cattle. They fished. They grew papaya, avocado and peanuts. They made okolehao, liquor distilled from ti root. “We grew our own food,” Sam remembers, “so we didn’t know there was a depression going on. We had little need for money. We made our own pipes for smoking. A pipe bought in a store was called ‘a lazy man’s pipe.’” Sam’s father and grandfather made canoes. Sam continued in this tradition, although as a carver of fine sculpture. He used adzes that came down to him from his ancestors. They were fashioned a century or so ago.

Herb Kane traveled to each island to introduce the concept of the voyage, taking the Hawaiian pulse at each encounter. In 1973, Sam Ka’ai went to Maui Community College to listen to Herb talk about Hokule’a. When the talk was over, Sam stood up holding a copy of Honolulu Magazine and pointed to a picture of the canoe. He spoke to Herb in Hawaiian. Herb said “speak English please.”

“We cannot participate in the making of your canoe because it’s going to be in Oahu, so maybe we can make some small part,” Sam said. “In the picture, there are two ki’is (sculpted figures) on the two manus – the two stern pieces of your canoe. Have they been made yet? If not, I will do it.”

It was a busy meeting so Sam gave Herb his address and left. A few days later, a letter arrived from Herb: “if you come from a canoe family, please dream and make your own design for the ki’is.”

Sam carved two ki’is – a man and a woman. The female figure would be lashed to the port manu, the male ki’i to the starboard. When Sam carved the male figure he fashioned his hands reaching up to the heavens in supplication.

“This is an effigy of how we are after so many years of oppression,” Sam explains. “Blind to our past, we reach up to grasp heaven one more time. The same stars are rising at the same time as they did for our fathers for many, many generations. So if you lose your way - if you cannot find your way – remember that you once sailed on your mother’s lap and you were never lost. The stars turned minute by minute, hour by hour, dawn and dusk and you always came home or your kind wouldn't be here. So you were never lost. This is an effigy of the Hokule’a experience – the ohana wa’a, the family of the canoe. He is reaching above himself, beyond himself, to the story that has not changed, the forever and ever story, the olelo, olelo, olelo - down the corridor of time – the lei of bones. He is showing that we are taking hold of the old story once again.”

You may also be interested in learning more about

my new book - Hawaiki Rising

Just click on it (below)

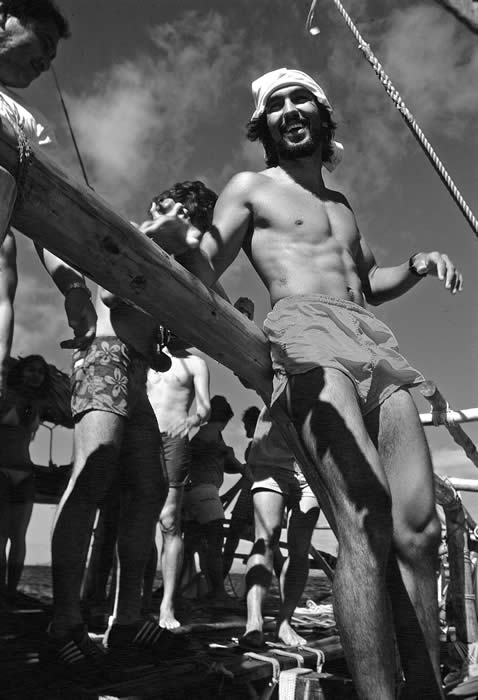

The Doldrums and Na'au

March 15, 1980

by Sam Low

Monte Costa photograph

Thirty years ago, Nainoa set out on his first voyage as navigator.

In 1980, after training for three years with Will Kyselka and Mau Piailug, Nainoa boarded Hokule'a as the first Hawaiian navigator in centuries to set out for Tahiti. In spite of all his preparation, he struggled with deep anxieties about the voyage. He felt responsible for the safety of his crew. He felt the weight of constant public scrutiny - of television cameras and news interviews. Mau had lived with the sea and the stars all his life, how could he expect to emulate even a part of his genius? And in the midst of a renaissance of pride among Polynesians, his success - or failure - took on new dimensions.

“I was afraid every day that I was in Hilo waiting to go. I constantly rehearsed everything that could go wrong - instead of focusing on how to make it work. I felt responsible for the crew's safety and also for the whole public arena, for doing well.”

“The day we finally left the Hilo breakwater stands out powerfully in my mind, because all of a sudden I felt much better. Now I focused on making the journey, not worrying about it. But I was still worried about staying awake. Mau never sleeps at sea. He can stay up all night, for weeks on end. I thought, "how in the world am I going to do that?" Not sleeping was part of Mau's magic, not part of mine.”

“Mau told me that the mind doesn't need much rest, but the physical body does. So when the navigator is on the canoe, the crew does the physical work. ‘When you are tired,’ he said, ‘you close your eyes.’ He told me that even though his eyes were closed, he is always awake in his heart. And when I sailed with him, I saw that was true. Preparing for the voyage, I tried to figure out how Mau stayed awake. I forced myself to stay up for a day or so but then I collapsed. I couldn't do it. So when we left Hilo I felt like I was voyaging both into an unknown ocean and into unknown regions of my own potential.”

“It was ten thirty at night. Tumor was rising, Maui's fishhook. I thought, "it's pretty late and I had better get some rest or I will be a basket case tomorrow."

“I lay down and closed my eyes. I thought, ‘how stupid you are. You are not prepared to go to sleep. You cannot sleep.’ So I got up and from then on I slept only two to three hours a day. When I became so exhausted that I couldn't think, I lay down. I slept until I dreamed. Then I got up. I slept maybe ten or fifteen minutes at a time and that was enough. My mind was refreshed. I learned to do that for a month. It was a whole new reality.”

As the voyage progressed and Hokule'a neared the equator, Nainoa worried about what would happen when the canoe entered the doldrums where hot air ascends from a three hundred mile wide belt of ocean. Here the constant northeast trades winds die off to be replaced by long periods of calm, followed by severe buffeting squalls, then windless days once more. It's a navigator's nightmare. Which way is the current taking me? How fast? From what direction did the wind blow in that last squall? In what direction did it push us? How far? Where am I?

“I dreaded the doldrums. I had no confidence that I could get through it. I thought that I could only accurately navigate if I had visual celestial clues, and that when I got into the doldrums there would be a hundred percent cloud cover. I would be blind. And that's what happened. When we arrived n the doldrums, the sky went black. It was solid rain. The wind was strong - about 25 knots - and it was switching around. We were moving fast. That's the worst thing that can happen - you are going fast and you don't know where you're going. I couldn't tell the steersmen where to steer. I was very, very tense. I knew that I had to avoid fatigue - I couldn't allow myself to get physically tense. But I couldn't help it. I just couldn't stop myself.”

“I was so exhausted that I backed up against the rail to rest. Then something strange happened. When I gave up fighting to find a clue in the sky and I settled down, then, all of a sudden, a warmth came over me. All of a sudden, I knew where the moon was. But I couldn't see the moon - it was so black.”

“The feeling of warmth and the image of the moon gave me a strong sense of confidence. I knew where to go. I directed the canoe on a new course and then - just for a moment - there was a hole in the clouds and the light of the moon shone through - just where I expected it to be. I can't explain it, but that was one of the most precious moments in all my sailing experience. I realized there was a deep connection between something in my abilities and my senses that goes beyond the analytical, beyond seeing with my eyes. It was something very deep inside. And now I seek out those experiences. I can't always do it. I have to be in the right frame of mind. I can't conjure up those experiences consciously. But they are coming more often now. It just happens. I don't want to analyze it too much. I just want to make it happen more often.”

“Before that happened, I tended to rely totally on math and science because it was so much easier to explain things that way. I didn't know how to trust my instincts. My instincts were not trained enough to be trusted. Now I know that there are certain levels of navigation that are realms of the spirit. Hawaiians call it na'au - knowing through your instincts, your feelings, rather than your mind, your intellect.

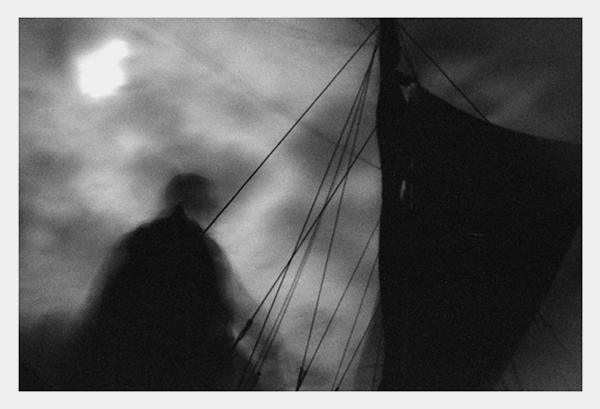

Lau Lima

A Laying on of Hands

By Sam Low

Photo by Monte Costa

Sailing Hokule'a with a crew of volunteers over routes not traversed for perhaps a millennium has presented many crises. One such occurred in May of 1997, when Nainoa hired a surveyor to inspect the canoe prior to its voyage to Rapa Nui.

A marine surveyor is empowered to say whether or not a vessel is seaworthy. He uses simple tools, a trained eye, a pocketknife and a rubber mallet. With his knife he probes for dry rot, a kind of virus that reduces wood to dust, although not obviously so to the naked eye. Poking in strategic places tells the story. If the knife goes in easily, the wood is rotten. Banging on the hull with a mallet may produce discordant notes to a surveyor's ear, another sign of problems.

After a few hours of poking and banging on that May afternoon, the surveyor made his report: "the canoe is rotten," he said. "I cannot certify her seaworthiness. I suggest you think about putting her in a museum." The pronouncement was a surprise but not a shock. Nainoa had seen places where there was dry rot, but the canoe had taken him safely across many oceans and had demonstrated more than seaworthiness, she had shown her mana, her strength of spirit. Retiring Hokule'a to a museum was not an option.

"I need two lists," Nainoa said to the surveyor, "I need a list of what's wrong with her, and a list of what to do to make her even stronger than when she was built."

The what-to-do list was long. Two of the wooden iakos had to be replaced - an onerous job but not exceedingly so. The hull was another matter. Wooden stringers run lengthwise from bow to stern, providing strength. There are five such stringers on each side, many of them rotten. The job of fixing all these problems fell to Bruce Blankenfeld.

In September, the canoe went into dry-dock. Perhaps "dry-dock" is a misnomer because it conjures a picture of Hokule'a in a mammoth shipyard cofferdam. Hokule'a's dry-dock was a shed in a decrepit section of the Port of Honolulu. Nearby was a junkyard with a tall fence and barking dogs, a pile of sand for making cement, a small marina, a few boatyards that did not appear very busy. Bruce set about finding workers.

"It's easy to find people when you're ready to go sailing but when you need them to maintain the canoe it can be pretty difficult. I had a group of young folk come down at the beginning of September and tell me they wanted to help. I said, 'well, it's pretty easy to do that. All you have to do is show up.' But after they saw all the work that was going on, they never returned."

What the prospective workers saw was nasty. Young men and women squirmed through hatches only slightly wider than their shoulders where they toiled for hours, in Stygian gloom, amidst fiberglass dust and the odor of polyvinyl resin. They excised the rotten stringers. They fitted new sections of wood. Then they "sister-framed" each stringer by adding two new pieces of wood, one on top and one on the bottom. Triangular wedges of foamed plastic followed for yet more strength and to "fair" the stringers into the hull. They sanded all this smooth and laid layers of glass fiber over it. They pushed resin into the fiber's mesh. When it hardened, the process was repeated. Then again. Three coats of resin; then two coats of paint. Meanwhile, other volunteers sanded off the hulls' gel-coat. Fiberglass dust veiled the canoe, clogging the pores of exposed skin. For eight months, Bruce found himself down at dry-dock at odd hours inspecting the work. Seeing his crew laboring over the canoe was like seeing a resurrection.

"Even though the work was hard, there was always a lot of energy. We saw progress every day. People are working together in the same place. It's usually dry and, compared to sailing the canoe, working conditions are luxurious. There are fits and starts, but everything seems to come together all right in the end. You are working on something that is very beautiful. You are touching the past with sandpaper and saws and rope lashings."

Bruce supervised his crew as they stripped the canoe's twin masts and brushed on eight coats of varnish and sanded each to the texture of baby-skin. Then they renewed five miles of rope lashings a few feet at a time. They ripped off deck planking, replaced and relashed it. The canoe received new iakos, new splashboards, and new manus fore and aft. She received stanchions, catwalks, hatches, and wiring for running lights and emergency radios.

An army of volunteers donated thousands of man and woman hours to Hokule'a's rebirth, a laying on of hands that expressed their deep commitment to the canoe and what she meant to them. They came from all walks of life. There is Russell Amimoto, for example, nineteen years old, a professional house painter and volunteer canoe lasher. He has served Hokule'a for three years. There is Kamaki Worthington, twenty-six, a teacher, fiberglasser, also a veteran of three years service. There is Kiki Hugo, in his forties, a cross country trucker who spends long months on the mainland driving from San Francisco to the Bronx, the Bronx to San Francisco, until he earns enough money to return home to Oahu. He is a kupuna, an elder crewmember with twenty-five years service. There is Lilikala Kamalehiva, fortyish, college professor, chair of the department of Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawaii, Hokule'a's chanter and master of protocol; Wally Froiseth, early seventies, once Hawaii's most famous big-wave surfer, now captain of the pilot boat of the Port of Honolulu; Jerry Ongies, early sixties, retired Army officer, ex-manager Dole Pineapple plant, boat builder, cabinet maker, canoe fabricator. This list of workers is an extremely small selection of the hundreds who donated their time to the canoe. The complete list would fill a book. If you were to ask these people why they have so freely given of themselves to the canoe they will provide a variety of reasons, unique to each of them, but there will also be a common response similar to what Nainoa once told an audience of legislators when they asked him why they should fund Hokule'a and her voyages.

"We must sail in the wake of our ancestors," he told them, "to find ourselves."

Finally, on the last week in March, the work was finished. The surveyor returned with his knife, his mallet and his well trained eye and certified the canoe "Lloyds A-1," nomenclature used by the world's largest insurer of watercraft to signify complete readiness for sea. A few days later, the canoe was launched. Among the men and women who tended Hokule'a as a giant crane lifted her from her cradle and laid her upon the ocean was Bruce Blankenfeld.

“The mana in this canoe comes from all the people who have sailed aboard Hokule'a and cared for her," Bruce said, looking out over the crowd that had come down for the launching. "I think of the literally hundreds of people who have come down and given to the canoe when she was in dry dock. I think of everyone who has shared similar work since she was first launched in 1975, those who have sailed aboard her, the men and women in all the islands we have visited who hosted us. All of this malama - this laying on of hands - adds to the mana of the canoe. It is intangible but it is alive and well."

Vision

Myron Pinky Thompson provided a core vision that we have carried on our canoes for the last thirty years. In essence, it is simple; in application, it is deep and complex. As president of PVS, Pinky's vision united past, present and future by reaffirming that traditional Polynesian values applied universally across time and space.

"Before our ancestors set out to find a new island," he explained, "they had to have a vision of that island over the horizon. They made a plan for achieving that vision. They prepared themselves physically and mentally and were willing to experiment, to try new things. They took risks. And on the voyage they bound each other with aloha so they could together overcome the risks and achieve their vision. You find these same values throughout the world, seeking, planning, experimenting, taking risks and the importance caring for each other."

"The same principles that we used in the past," he often said, "are the ones that we use today and that we will use into the future. No matter what culture we are, or what race, these are values that work for us all."

CREW PROFILE

Abraham "Snake" Ah Hee

2000 Hawaii to Tahiti

by Sam Low

"My father taught me to get lobster without a spear," Snake Ah Hee explains, "you have to be gentle, have a good hand, or you spoil the hole. If you do it right you can come back in a few days and there will be another lobster there."

Snake was born on March 18, 1946 in Lahaina, Maui. He lived for a time with his great grandfather in a house on the ocean outside town. "It was a fishing family. "We had nets and canoes and ever since I was a small kid my dad took me fishing. I learned the different areas to fish, how to find the fish, how the current moves, how to steer a canoe using Japanese oars." Snake's father, Abraham Ah Hee, Sr., was called "Froggy" because he swam so powerfully and could stay underwater so long. Like most Hawaiians, Snake began to surf as a youngster, gradually becoming comfortable in big waves. He surfed for a time with the Wind and Sea Surf Club, a California group, and in contests he often went home with a cup marked "first place." Later he was on the Gregg Knoll surf team and paddled for the Lahaina Canoe Club where he was also a coach. "I still love to surf," Snake says, " and I hope to do it into my eighties. The ocean has taken hold of me spiritually and mentally. I think it’s because it’s tied in with my family, with being raised on the ocean."

Snake graduated from Lahainaluna High School in 1964 and worked as a life guard at hotels on Maui. He joined the National Guard and was called up in 1968 to go on active duty - one tour in Vietnam. He served in the Southern war zone, not too far from Saigon, and he rose to be a squad leader in charge of patrols.

"It made my mind stronger," he says, "more adult. It taught me the value of life. It's crazy to fight. I hope my children will never go to war. I want to see peace - all the time - all over the world."

Snake has five children, three girls and two boys: Malia Mahealani, Nainoa Chad, Makalea Rose, Mau Nukuhiva, and David. It’s not an accident that the names Nainoa, Chad and Mau appear in this family. "Hokule`a brought all her crew together, "Snake says, "we're like a family of brothers and sisters. I can go anywhere in Hawaii and stay with my `ohana. On the Big Island, for example, I stay with Shorty or Tava or Chad; on Moloka`i maybe with Mel Paoa or Penny Rawlins. I might not see them for a year but when I do it seems like just a short time."

In 1975, Snake first heard about Hokule`a and that she would sail to Tahiti, but he had never laid eyes on her. "Then one day I was in my truck on the way to the canoe beach and I saw this boat coming from Lana`i. 'What's that?' I thought. I stopped. I had never seen anything like it before."

Later, George Paoa and Sam Ka`ai came to the beach where Snake was life guarding and asked him to be a member of the crew. He began training right away and was chosen for the return trip from Tahiti to Hawai`i. That's where he first met Nainoa.

"That trip gave me a real good feeling inside," Snake remembers, "It was a good thing for my generation. The canoe makes us strong in mind and spirit - close to our culture. If not for the canoe I won't say that our culture would be lost, but it would be weaker. It helped bring back the language, and helped bring back the community, not only in Hawai`i but throughout all the Pacific - wherever she has stopped."

"On this trip," he continues, "I’m here to teach the younger generation who are sailing with us - how to take care of themselves and each other - how to be humble. For me that's the one key part. If you’re humble everything will be fine. Everyone will think the same, work the same, be closer together. Only if you are humble can you learn."

CREW PROFILE

Pomaikalani Bertelmann

2007 - Voyage to Satawal

By Sam Low

A generation or so ago two Bertelmann brothers married two Lindsey sisters and the trajectory of history in the Big Island town of Waimea shifted slightly. Glenn Bertelmann and Delsa Lindsey had seven children and Clay Bertelmann and Deedee Lindsey produced five - a tight family with deep roots in a much larger `ohana that thrived beneath the gentle catenary arc of Mauna Kea. In Clay and Deedee's family, Pomaikalani was the first-born - on March 7, 1973, in Honoka`a. At the time, her father was a well known Parker Ranch cowboy, so it's not surprising that young Pomai grew to love horses - in fact, animals of all kinds.

"I was basically raised on my family's ranch and riding was a passion since I can remember," Pomai says. "I also worked as a kid on Hale Kea ranch in Waimea, fixing fences, raking the arenas, exercising horses and taking care of the livestock."

Waimea was less dressy in those days, an informal rural town where children could safely ride horses along the main street and in the surrounding empty pastures. They rode to the Dairy Queen drive-up window to order hamburgers, they staged informal barrel and baton races and played "musical chairs" in the vast empty prairie just outside town.

"A sense of community was second nature among us," Pomai says, "there were kids from all the families - the Keakealani family, also Rebozos, De Silvas, Kimuras, Lindseys - a lot of Lindseys - Kainoas, Colemans, Kanihos, Kaauas, Bergins, Awaas, Purdeys and the Fergerstrom family - to name a few. All of us were kaukalio (riding horses)."

One of the biggest events in Waimea was the fourth of July rodeo organized by the Parker Ranch Roundup Club where cowboys from the ranch's numerous divisions competed in various events - cutting, roping, racing.

"The cowboy life style was not exclusive of women, not at all. There were a lot of awesome women riders too. Lorraine Urbic sat a horse like no one else, and she won a lot of races. Then, just to name a few, there was Hoppy Whitehead, Val Hanohano, and Peewee Lindsey - all of them very strong people - great role models for us."

But life in Waimea embraced more than the land-based culture of the Paniolo.

"One of my fondest memories," Pomai explains, "was loading up the family Bronco with my mom and dad and the five of us kids and then picking up all my cousins and food and camping gear and heading for the beach. We went to a place called Wailea at Puako. There was no one there in those days. We had the place all to ourselves. Right next to where we used to camp there’s a telephone pole with the number "69" printed on it. Since then, things have changed. Malahini now call Wailea "number sixty-nine". When you lose the real Hawaiian name, you lose a lot.”

At Wailea and other places, Pomai learned to dive with her father and she enjoyed fishing but never really grew fond of other water sports. As a youngster it was always the life kaukalio and with animals that attracted her most. But in 1975, her Uncle Shorty sailed aboard Hokule`a on her maiden voyage to Tahiti.

"We supported him as a family, and whenever the canoe came to the Big Island we helped care for her and her crew."

During the series of voyages between 1985 and 1987, Pomai's father Clay sailed often aboard Hokule`a.

"He was away at sea for maybe six months during those two years, and I began to wonder a little about the kind of life he was leading."

Gradually, Pomai's family was becoming more and more entwined with the sea. From 1989 to 1991 the Bertelmann family helped search the forests surrounding Mauna Kea for koa logs to build Hawai`iloa. They cooked and packed food for the searchers, walked side by side with them during long weekend treks - took a key role in the entire process. Ultimately, so devastated were Hawai`i's forests, that no logs were found and the canoe was built instead of Alaskan spruce. But from this effort, Mauloa was born - the first traditionally made Hawaiian six man coastal canoe fashioned within perhaps centuries.

"We did find Koa logs big enough for a smaller canoe," Pomai explains. "We went to Keahou to fell the trees and we lived there over a long weekend in tents."

The canoe builders used adzes that they fashioned from stone gathered at the ancient Keanakakao`i adze quarry on Mauna Kea under the watchful eye of Mau Piailug. From 1991 to 1993, Pomai's father Clay spent every weekend at Pu`uhonua O Honaunau working on the canoe.

"In traditional times women were not allowed to work on canoes so we supported the men," Pomai explains. "Mauloa was built by the Na kalai wa`a - the canoe builders - from Koa and Breadfruit sap and sennit and Lauhala, her hulls were smoothed by stones and she was given a sheen with Kukui oil.

In 1992, Pomai went with her father to O`ahu to help him prepare for Hokule`a's voyage to the Cook Islands. There she met a group of young people who were beginning to assume leadership roles - Moana Doi, Keahi Omai, Ka`au McKenney and Chad Paishon, who she would eventually marry.

"I began to think seriously about my life in 1992," she remembers, "and as I learned more about the values involved in voyaging, I thought I wanted them in my own life. Voyaging gave me a sense of family - which was familiar since I had grown up in a strong supportive family - and it gave me a connection to my cultural roots. And when Mau Piailug began to stay with us I met a man who had done so much for our people - how could I not be excited?"

Next came Makali`i - the Big Island canoe built by a passionate community effort spearheaded by Clay, Shorty and Tiger Espere. Beginning work in January 1994, the canoe was finished the following December. In September, Pomai became - as she puts it - "a one woman administrative staff," for Na Kalai Wa`a Moku O Hawai`i - The Canoe Builders of Hawai`i. She was hooked.

In 1995, Pomai sailed aboard Makali`i from Tahiti, through the Marquesas, and back to Hawai`i. "Then in 1997, Mau asked us to take him home to Satawal on Makali`i and, of course, there was no question about it." In February of 1999, Makali`i raised anchor and set out on the voyage called E Mau - "Sailing the Master Home."

"We sailed to many islands in Micronesia to honor Mau among his own people," says Pomai. "On Satawal I saw Mau as a complete man for the first time - not just as a navigator - but also as a father, a husband, a fisherman, a farmer - you should see his taro patch. I have never seen him so happy."

Soon after Makali`i returned from Micronesia, Pomai was once again deeply immersed in organizing the details of caring for the canoe and organizing it's many educational voyages. Through the intimate grapevine of Hawaiian sailors, she learned of Hokule`a's upcoming voyage to Rapa Nui. "I also heard that it might be Nainoa's last voyage as a navigator," she remembers, "and I was heart broken. I always wanted to sail with him. I thought I might never get the chance." A short time later, Nainoa called and invited her to come aboard Hokule`a for the fifth leg - the voyage home.

"This is such an honor for me," Pomai says, "to have a chance to not only learn from Nainoa but from the greatest sailors of the last quarter century of traditional voyaging - from Uncle Snake and Uncle Mike and Uncle Tava. I’m now sailing with the guys who started the renewal of our ancient voyaging arts and contributed to the beginning of the revival of our Hawaiian culture."

The "Old Men" of Tautira

by Sam Low

You could imagine a meeting like this in a thatch-roofed canoe house hundreds of years ago with the visitors' double-hull voyaging canoe drawn up on the beach outside. But this meeting is held in the white-washed conference room of Tautira's mayor - Sane Matehau - and the date is January 27th, the year 2000. Only the feeling is ancient - a sharing of stories by friends from distant islands, a bonding together of a wide-spread `ohana.

Outside the conference room, the setting sun colors clouds over nearby mountains and a cool wind washes ashore over the reef. Inside, we are seated in a circle with representatives of Tautira's community, including Kahu from the Protestant, Catholic and Mormon churches. Sane has called the gathering to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the joining of Tautira's people with the people of Hawai`i.

The first to speak is Tutaha Salmon. For a Tahitian, he appears almost delicate, yet his bearing is dignified, suggesting confidence. His graying hair indicates he may be in his seventies. Tutaha was once the mayor of Tautira – a position now held by Sane - his son-in-law. He is now the governor of a large Tahitian district including Tautira and three other towns: Faaone, Taravao and Pueu.

"It’s an honor that whenever Hokule`a sails to Tahiti she lands here in Tautira," Tutaha tells us. "How many times have you come? I cannot count them. But what's important is that you are now our family - our brothers and sisters."

Following protocol that is ancient, Tutaha then speaks of his elders. The enfolding story of Hokule`a's relationship with Tautira began with "the old men" - a six-man canoe team who paddled their way into the history books

"Our dream of cultural exchange was born twenty-five years ago. In those days the man I remember first is Puaniho. He has now passed on but he showed us the way. He was a quiet man, but powerful. There was Mate Hoatua the steersman on the canoe from Haleolono to Waikiki. He steered the whole way, without relief. Henere, Tevae, Nanua and Vahirua paddled the canoe. We called them "the old men" because their minimum age was fifty. This is our time to remember them and to tie that rope tight to the mast."

"The old men" of Tautira's Maire Nui canoe club first traveled to Hawai`i in 1975 to compete in the Moloka`i race. Pinky Thompson next rose to speak in response to Tutaha's welcome.

"I want you to know that we feel at home ever since you took a strange looking Hawaiian youth into your homes 25 years ago, my son Nainoa. You recognized immediately that he was a stranger in a land that was strange to him and you malama-ed [took care of] him."

Nainoa came to Tautira in 1995 as a member of Hokule`a's crew. He recognized immediately that the "old men" of Maire nui paddled differently then any team in Hawai`i.

"They were so smooth," Nainoa recalls, "their movements were fluid, no lost energy, and their canoe seemed to leap forward - faster than anything I had every seen.”

He wanted to learn from them and in 1977 he got the chance. In that year's Moloka`i race, Nainoa's team from Hui Nalu lined up next to "the old men."

"They were twice our age, and we were a pretty strong crew but they left us in their wake, paddling easily."

In that same year, Nainoa traveled to Marina del Rey to serve on a motor boat escorting Maire Nui in the Race to Newport Beach, California.

"They finished the race, took a shower, and were drinking a beer before the second place canoe arrived. They beat them by an hour and 4 minutes."

Nainoa invited Maire Nui to stay in Niu Valley when they came to Hawai`i in 1977 for the Moloka`i race and again in 1978 when they won the koa division for the third consecutive time – retiring the famous Outrigger Canoe Club cup to an exhibit case at Sane Matehau's home in Tautira. Over the years, visits by Maire Nui to Hawai`i and by Hawaiians to Tahiti continued. Puaniho built a Koa canoe for Hui Nalu and later another famous Tautira canoe builder flew to Kona to build six Koa canoes - helping to inspire a renewal in traditional canoe building that thrives today.

Nainoa, Bruce, Pinky and their Hui Nalu colleagues studied the Tahitian way of paddling and became champions themselves. Pinky remembered those moments in his presentation at the Mayor's office.

"You helped us become champion paddlers, but you did much more than that. You helped us to return pride to our Polynesian people by restoring our native craft of canoe building and paddling."

"’The old men’ taught us what it means to be champs,” Nainoa added. “It's not about outward appearance. It's about what happens inside. They didn't talk much because they knew that the mana comes from within. They didn’t think of themselves representing just a club - they represented all their people.”

Shantell Ching - In the Zone

2000 - Tahiti to Hawaii

By Sam Low

For the past week, Shantell Ching, navigating Hokule'a home, has gone without appreciable sleep.

"I catnap" she says, "for maybe an hour or so a day. Last night, I was so tired that my head was bouncing. I like to sit in the navigator's seat but I was afraid I might go to sleep and fall overboard so I moved over to the platform."

What Shantell is going through is part of any navigator’s rite of passage - attaining the mental and physical stamina needed to constantly process a steady flow of information and make good decisions.

"It takes a lot of adjusting just to get in synch with the ocean after being on land for so long, " Shantell explains. "I need to get to where I can mentally see the canoe in the middle of the star compass in the middle of the ocean - so I see the compass points on the horizon. I have to reorient myself to the southern stars, for example, so I don't have to think about where they will come up but I seem to know by instinct".

Most top athletes attain a similar instinct when they’re performing at their peak. Basketball players, for example, report having "eyes in the back of their heads." They know what’s happening in the court all around them - how other players will move, where the ball will be. "I'm in the zone,” they say. Sport psychologists think to enter ‘the zone’ a top athlete must learn to use both sides of his brain, first mastering the mechanics of the game in the right-hand, rational side of the brain – then switching to the left side, the control center for human artistry, to become truly creative. The process that Shantell describes seems to be similar. She's entering her own version of ‘the zone’.

"I’m gradually getting the entire sky in my head, " she says. “I’m getting a good feel for how the waves make the canoe move when we're steering different courses. I need to get in synch with the canoe - to feel in my body when she’s pinched too far into the wind or when she’s sailing too far off the wind - when she’s struggling and when she’s free."

"Lack of sleep is no longer a problem. I can be immersed in the navigation, for example, but when we encounter the beginning of a squall I snap right out of it and know exactly what to do. I’m right there. I’ve been learning about navigation now for six years and this is a chance to apply what I've learned. If I’m successful, the credit goes to my teachers – to Nainoa and to Bruce and Chad. And, really, to all the teachers who inspired me. When I was in elementary school I was too young to understand how important math would be in my life but a lot of navigation is basic math - addition, subtraction, simple trig. Now, when I solve a math problem in my head, I thank all those teachers who were strict with me".

"I can see Hawai'i in my mind and that's a good sign. Nainoa taught me that to find an island, you first have to see it mentally - and that’s also what Mau taught him."

Crew Profile - Tava Taupu

2000 - Tahiti to Hawaii

by Sam Low

On April 6, 1945,Tava was born in Taiohae on Nukuhiva, Marquesas Islands. His father worked on a sailboat that made interisland trips carrying passengers. As a young man, Tava went to Tahiti to learn to carve wooden tikis from his uncle Joseph Kimitete. Pape'ete, the capital, was a place where young Tahitians like to rough up boys from the outlying islands, so Tava learned to box.

"When I went boxing, I got proud," he recalls. "I was amateur, six rounds. I won't drink anymore. I exercise, forget kid stuff, no more smoking cigarettes." What Tava doesn't tell you is that he boxed so well he earned the title of lightweight champion of French Polynesia.

"I first learned about Tava's boxing when I was on a voyage with him in 1980," recalls Chad Baybayan. "We were going to go out on the town and Tava began to get dressed up. Then he stood in front of the mirror and began shadowboxing. It was scary. I always knew him as an extremely gentle person, and now I was seeing his wild side. When we went into the bars, he would walk in the door like a superstar. People came up to talk to him. I was surprised how many people knew him in Pape'ete."

In 1970 Tava came to Hawai'i on a visa arranged by Kimitete's son. He worked at the Polynesian Cultural Center in La'ie building traditional houses and carving tikis - in general carrying on the traditional arts of the Marquesas. In 1975, he saw Hokule'a for the first time.

"When I saw Hokule'a, I think 'what is this big canoe?' I never see big canoe like this in the Marquesas. We have 30-foot canoes with outriggers, single canoe, not double canoes. I am excited. It all comes back to me - my ancestors. I feel my ancestors all around me. I wonder how they sail this canoe? how they survive on the ocean? Right after seeing her, I began to work on her. I work at my job all week and go spend weekends working on the canoe."

In 1975 Tava sailed on Hokule'a interisland. Later he learned from Mau Piailug how to build canoes in the traditional Pacific Island way, with sennit for lashing and coconut husk and breadfruit sap for caulking. At about the same time, he met Nainoa, who was just beginning to study the stars.

"I met Nainoa at Ala Wai. He is a very quiet guy because there is something he is learning by himself - the stars. I see him looking at the sky. I never know what he is looking at. 'What you looking?' I ask. He say, 'I looking at stars. I learning navigation, to be a navigator.' I try speaking Tahitian to him but he no understand me. He look at me and say, 'Sorry I can't understand.' He was really quiet, and I very quiet too. I ask him what he looking at and he point to the sky. 'You see that star over there?' he says. He tells me navigator star. I don't know which one. I say to myself, 'What’s that ‘navigator star?' I keep quiet but I thinking, what’s that navigator star?’"

Since meeting Nainoa and beginning to voyage aboard Hokule'a, Tava has sailed at least one leg on each major voyage. "I always ask Tava to come with me," Nainoa says. "Tava loves the canoe and what it stands for. He gives the canoe his life, and the canoe gives him her life. Tava takes care of me while I am at sea and he provides a net of security around the entire crew. He makes it comfortable for me to concentrate on navigation."

During one voyage, an important piece of equipment went overboard, and Nainoa impulsively went in after it. When he finally got back on board, he was shivering uncontrollably - near hypothermia. "I was just sitting there on deck unable to get warm and Tava came up from behind me and hugged me; he shared his warmth so his friend would not be cold."

Tava's personality emerges from what others say about him:

“First impressions of Tava can be off-putting - his head is shaven and he is clearly a strong man. If you saw him in a dark alley, you would surely turn around and walk the other way. That impression is rapidly dispelled when you meet him. There is a firm welcoming hand shake and a smile so genuine that it warms the room.”

“He's genuinely kind. He lives by the standards he learned as a child growing up in the Marquesas."“He bridges the gap between the old and the new, between traditional and modern society. If you see him being greeted by the older people throughout Polynesia, you see the respect he is given.”

“He is powerfully intelligent, yet clear and direct in his thoughts and expression. He is clear about his role on this canoe.”

“He has a pure spirit and puts me at ease when I'm with him.”

“He sees what needs to be done and does it. He makes himself an integral part of doing any task. There is no work too hard for him.”

“He is a quiet, caring and gentle person, always there when you need him.”

“One of the most loving human beings I have ever met.”

“To look at him, you would be scared. Who is this guy - bald headed and mean looking? But he is a kind, kind man.”

It was surely the warm, loving side of Tava that his wife Cheryl saw in 1980 when they first met. Tava and Cheryl have two children - Rio, 18, and Helena, 6. Today when Tava is not sailing, he works for the National Park Service at Pu'uhonua o Honaunau, as a cultural expert, demonstrating wood carving and canoe making.

"I like working there. Sometimes I work in the halau, sometimes I work on the roof, sometimes carving, or building a stone wall."

Over the last 25 years Tava has become so integral to Hokule'a that to see her without him standing on her deck at the forward manu, dressed in his bright red malo would be like seeing the canoe with only one mast - or with some other key part of her missing. Yet this trip back from Tahiti may be his last.

"It's time for retirement. I am 55 years old. I like see my wife on the land. I like build my house now. I am excited."

Even so, in conversation with him on this voyage, it is clear that what Nainoa says of Tava is true - that he gives life to the canoe and receives life from her. When he leaves Hokule'a he will leave an important part of his life behind. "I will be sad because I am used to voyaging. But better for me to stay on land. I feel like crying, but I no cry. That is my rule - always show a smile to the canoe."

It's not that he will ever leave the canoe or her family completely, because he plans to make interisland voyages aboard her and because he knows he has left a part of himself behind with the new younger crew members.

"I come on the canoe when I am young, and now I am looking. Maybe some of the young people are like me. It's time to leave the canoe, so the young people can learn. You have to learn to sail by hand - how to steer, how to trice, how to look at other people, how to behave. The canoe's mana means all the crew take care of the canoe and the canoe take care of the crew. The canoe take you all the way home."

"When I don't sail, I don't feel bad if I have trained other people. It is for you now, like Chad, like Bruce, like Shantell, like other young people. It's your turn."

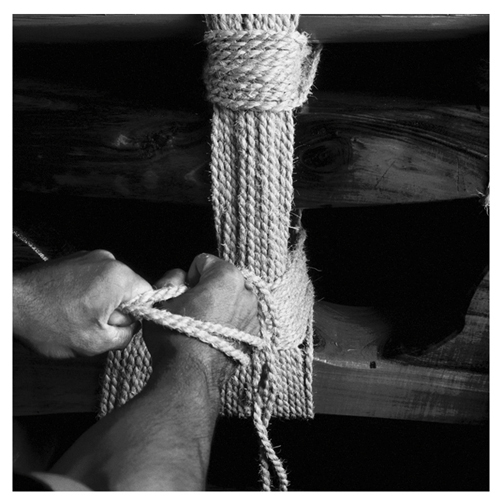

Wayfinding

Chad Baybayan

by Sam Low

Chad Baybayan stands about five feet eight inches. He has a swimmer's body, suggesting a capability of delivering powerful strokes and a strong finishing kick. He is dark both by genetic makeup (he is part Hawaiian, part Filipino) and because he spends a lot of time in the sun attending to his duties as one of Hokule'a's navigators. Chad will readily tell you that voyaging aboard the canoe has been the seminal experience of his life - accounting for the fact that he is about to receive a master's degree in education, for his happy marriage and fatherhood, for his inner sense of confidence.

"When I first saw Hokule'a in 1975, it just grabbed my heart. I knew that if there was anything in my life that I wanted to do it was sail on her."

For a time, it appeared that Chad's wish might not happen. Chad was too young for the 1976 voyage to Tahiti. In 1978, when the canoe swamped on a second journey, it looked like voyaging might end. But shortly thereafter, new management took over the Polynesian Voyaging Society and Baybayan spent countless hours working with sandpaper and paintbrush, helping to overhaul the canoe for another voyage. In 1980 he made his first ocean passage to Tahiti as the "youngest member of the crew" and began to study navigation by "asking Nainoa Thompson (the canoe's navigator) a lot of questions." During the next nineteen years he spent as much time as he could afford aboard the canoe, eventually working his way up the informal hierarchy to full fledged navigator.

Among Hokule'a's navigators (there are three other fully qualified ones - Nainoa Thompson, Shorty Bertelmann, Bruce Blankenfeld) Chad may be the most charismatic, and it is for this reason that he is often chosen to be the Voyaging Society's spokesman. So it was that one evening in May of 1998, Chad stepped forward to talk to crew candidates for the upcoming voyage between Hawaii and Rapa Nui. The men and women assembled before him were about to go through a final four day training session that would include an open ocean swim of nearly two miles, a sail aboard Hokule'a, and many hours of testing their navigation and seamanship skills. They all knew each other well. Most of them, excluding a few young rookies, had sailed on previous voyages during the canoe's twenty-five year career.

"You are all here because you share a powerful vision for Hawaii," Baybayan told them. "And that vision joins you together across differences in ethnicity and race and where you may have been born and raised. You share a common desire to make this world better."

Baybayan's notion of ethnic and racial unity was not always a part of the voyaging consciousness. The early 1970s marked a cultural revival among Hawaiians that inspired not only pride but also renewed painful memories of a history marked by near genocide, loss of land, and culture. The times were ripe for sectarianism. On the first voyage to Tahiti in 1976 - a near mutiny was inspired by some crewmembers who felt that only authentic Hawaiians, as they defined it, should be allowed aboard the canoe. But now, almost twenty-five years later, seated before Baybayan were men and women of many extractions - Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Hawaiian, Portuguese, German, English, American. They had shared hundreds of hours working together during which potential differences between them had come to mean not a whit.

Confronting the sea on long voyages, Chad has had much time to integrate all that he has learned and he has done so by bundling an astonishing number of lessons into a general philosophy that he (and the other sailors and navigators as well) calls "wayfinding."

Chad distinguishes wayfinding from navigation - the technical art of finding land without the use of instruments or charts. He will tell you that wayfinding is "a way of organizing the world." He has also said that it's "a way of leading," "of finding a vision," "a set of values," "how to take care of the earth," and, in general, "a model for living my life."

Chad's vision of wayfinding eventually evolved to contain principals that appear astonishingly universal and timeless, while, at the same time, being rooted in values that Hawaiians have come to recognize as inherent in their own unique history. Values like vision, for example.

"Our ancestors began all of their voyages with a vision," Baybayan explained during his talk to the assembled crew. "They could see another island over the horizon and they set out to find these islands for a thousand years, eventually moving from one island stepping stone to another across a space that is larger than all of the continents of Europe combined."

"After many years, I began to understand that wayfinding was really a model for living," Chad continued. "Once you have the vision of a landfall over the horizon, you need to develop a plan to get there, how you are going to navigate, how much food you need. You must evaluate the kinds of skills you need to carry out the plan and then you must train yourself to get those skills. You need discipline to train. Then, when you leave land, you must have a cohesive crew - a team - and that requires aloha - a deep respect for each other. The key to wayfinding is to employ all these values. You are talking about running a ship, getting everybody on board to support the intent of the voyage, and getting everybody to work together. So it's all there - vision, planning, training, discipline and aloha for others. After a while, if you apply all those values, it becomes a way of life."

Chad Baybayan's concept of wayfinding is not exclusive to him. It is, in fact, a voyaging subculture shared by everyone who is attracted to the canoe and who sticks around long enough to learn the lessons it has to teach.

In the last decade or so, the philosophy of wayfinding has "moved ashore" so to speak. New words have entered the wayfinding vocabulary, "stewardship" for example, or "sustainable environments." Lessons learned at sea are now being applied to the land. The ancient philosophy of wayfinding is now merging with the new world view of environmentalism, as Chad explains: "To be a wayfinder, you need certain skills - a strong background in ocean sciences, oceanography, meteorology, environmental sciences - so that you have a strong grounding in how the environment works. When you voyage, you become much more attuned to nature. You begin to see the canoe as nothing more than a tiny island surrounded by the sea. We have everything aboard the canoe that we need to survive as long as we marshal those resources well. We have learned to do that. Now we have to look at our islands, and eventually the planet, in the same way. We need to learn to be good stewards."

This new vision is at the core of the Voyaging Society's "Malama Hawaii" program which we celebrate on this voyage home.

"At the beginning of this new millennium, we honor the first 25 years of Hokule'a's life and the achievements we've all realized working together," Nainoa once said. "Since 1975, the canoe has sailed more than 90,000 miles, taking us to each of the points of the Polynesian Triangle. We've learned a lot during these voyages - the power behind shared vision, the energy generated through collaboration, the continuing thrill of exploration and discovery and the joy of kinship."

"But by far, the most compelling lesson we've learned in all of our travels has to do with home. We've come to appreciate anew, the uniqueness of Hawaii and her people and our responsibility to work together to maintain that uniqueness."

"Learning to live well on islands is a microcosm of learning to live well everywhere. Here in Hawaii we are surrounded by the world's largest ocean, but Earth itself is also a kind of island, surrounded by an ocean of space. In the end, every single one of us - no matter what our ethnic background or nationality - is native to this planet. As the native community of Earth we should all ensure that the next century is the century of pono - of balance - between all people, all living things and the resources of our planet."

Chad as a young man aboard Hokule'a

Hokule'a under bare poles

on the way to Rapa Nui

CREW PROFILE

Joey Mallott

Tahiti - Hawaii 2000

by Sam Low

"When I was younger, I fished with my Dad every summer," says Joey Mallott. "We went power trolling for salmon and long lining for halibut in the Gulf of Alaska. It was a lot of hard work and long hours. The waters were rough and cold. We also fished for Coho salmon in the Inside Passage. Sometimes the water was mild and we would nest up with other boats in an isolated cove, cook dinner, tell stories. In the morning we woke up surrounded by an almost undisturbed wilderness. It was beautiful."

The Inside Passage is a legendary waterway - often violent and extremely dangerous, about which author Jonathan Rabin wrote this in his recent book, Passage to Juneau: "The water on which the northwest coast Indians lived their daily lives was full of danger and disorder; seething white through rocky passages, liable to turn violent at the first hint of a contrary wind, plagued with fierce and deceptive currents. The whirlpool - capable of ingesting a whole cedar tree, and then spitting it out again like a cherry pit - was a central symbol of the sea at large, and all its terrors."

Joey was born in Anchorage, Alaska on June 2nd, 1977 to Byron and Toni Mallott. Through his father, he was also born into the Killer Whale clan of the Eagle moiety of the Tlingit Nation and through his mother into an Athabaskan group of people - more specifically the Koyukon Tribe who lived in the interior of Alaska on the Yukon River.

"I spent most of my summers growing up in small Indian villages," Joey says. "My parents wanted me to have that kind of experience, living in small indigenous communities rather than in big cities."

Joey's father, Byron Mallott, is well known among his people. He was born in a time when you saw signs posted which said "No Indians and Dogs Allowed."

"From a young age my dad was motivated by a strong desire to help his people," Joey says, "because he saw a lot of pain among them and the problems of poverty, alcoholism and high rates of illness and early death. He worked hard all his life. When he was only 18 he captained a 56 foot schooner from Washington to Yakutat on the inland passage."

Growing up on this difficult ocean, Byron Mallott learned early to be determined to reach his goals, either at sea or on land among his people. As a young man of only 34, he was appointed Chief Executive Officer of the Sea Alaska Corporation, which manages a huge tract of land belonging to native Alaskans, and he used funds from this enterprise to help lift his people from poverty and depression. Joey Mallott lived with his grandmother as a boy where he learned many of the same values that have motivated his father.

"The day I arrived in her village," Joey says of this experience, "my grandmother handed me a 4/10 gauge shot gun and told me to get dinner. She taught me how to hunt, fish and trap and to live and survive in the outdoors, but more important, her lessons were about patience and kindness and about being open to everyone you meet."

Joey graduated from elementary school and high school in Juneau, Alaska and went on to earn his Bachelor's degree in Elementary Education at the University of the Pacific in 1999.

"Life in college was different than the way I was raised. I saw a lot of vanity there and selfish acts."

In 1991, Nainoa first traveled to Juneau to meet with Byron Mallott to discuss receiving the gift of two giant spruce trees from the Sea Alaska Corporation to build Hawai`iloa. The two men became fast friends which led to a joining of the Thompson and Mallott families which Joey describes as "one single family."

When Pinky Thompson asked Nainoa to choose an Alaskan representative to journey on at least one leg of the voyage to Rapa Nui Joey was offered the position. "I got the call in 1998," Joey remembers, "and I knew right off that I wanted to go."

In 1999, Joey moved to Hawai`i where he now lives with his girlfriend Lissa Jones in Pauoa Valley on O`ahu. "I wanted to take some time off between college and beginning my teaching career, and we both like the idea of living for a while in the islands. Besides, I have family here now."

The experience of being involved with building Hawai`iloa and living in the islands has allowed Joey a deep insight into Hawaiian culture. "I think there’s a great deal of similarity between any indigenous culture and how we view the world. That's why Hawaiians and Native Alaskans share so many values. We both respect our elders and believe in taking care of our environment, for example, and we’re motivated to recover our native traditions and pride and to bring back our sense of community."

In time, Joey expects to return to Alaska to begin his career as a teacher. When he does, he will bring with him a vision inspired by sailing aboard Hokule`a and Hawai`iloa.

"My people were a seafaring people," Joey explains. "When my father was a young boy he saw large dugout canoes which were used for fishing and traveling from village to village. They’re still made today, but mainly as works of art, not for sailing. One of the first things I want to do when I get home is start a project to build a traditional canoe in the traditional way."

CREW PROFILE

Kaui Pelekane

Tahiti - Hawaii 2000

By Sam Low

Among those called to medicine, it is probably accurate to say that the innermost sanctum of practice is the operating room of a major hospital. A hospital like The Queen's Hospital in Honolulu, Hawai'i's largest, where Kau`i Pelekane has been a surgical nurse for the last four years. Her ascent to this extremely demanding position has not been easy - calling for a complex juggling act in which the needs of a career had to be matched always against those of her two children, Ikaika and Kaimipono, now thirteen and eleven years old.

Kau`i was born in Long Beach, California on January 24, 1965, but was raised in Kailua-Kona by her parents Mike and Monique Pelekane. In 1983 Kau`i graduated from Konawaena high school and enrolled in nursing school at the University of Hawai`i, which she attended for a year before taking time off to marry Tim Mencastre (they are now divorced) and begin having children. To support her family, Kau`i worked for a time at a bank.

"Then I began to consider my life and my responsibility to both myself and my kids and I decided that I didn't want to be a bank teller for the rest of my life," Kauai says. "When I was in high school I worked in a doctor's office as a secretary and when the doctor did minor surgery I occasionally was called on to assist him. I found that I liked helping people and I think that's where I got the idea to become a nurse."

In 1989, pregnant with her second son, Kau`i returned to nursing school, enrolling in a two-year associate degree program which resulted in her qualification as a registered nurse. For three and a half years she worked in the oncology ward and then learned that Queen's was opening a six month surgical training program. Only four applicants would be accepted from many candidates.

"I got in the second time I applied," Kau`i explains, "and now I have been working as a surgical nurse for four years. It's very intense sometimes," she adds, "but I really feel that I am helping people."

Although Kau`i was born on the mainland, she doesn't remember much about her life there because she was so young when she returned to Hawai`i.

"My family on the Big Island was heavily involved in paddling," she remembers, "and they started the Kaiopua canoe club in Kona. I have been paddling since I was ten years old. My dad took me fishing and taught me how to pick `opihi. My family had a catering business so I learned how to cook for a luau. In Hawai`i," she continues, "we had avocado trees and never paid for fish. Vegetables and other fruits came from our neighbors. When I first moved to O`ahu I couldn't get used to buying fish in the market " - here Kau`i pauses for a moment to laugh at herself - "and I refused to pay for fish for about a year."

Today, Kau`i and her two children live in Kailua and she paddles for the Hui Nalu canoe club where she first met Nainoa.

"I have always known about Hokule`a," she remembers, "but I never dreamed that I would ever sail aboard her. Then, late in 1998, Nainoa asked me if I would be willing to be the medic on board for the last leg of the Rapa Nui voyage. How could I say no? Even though I had big reservations about it - taking on such a large responsibility - I said 'yes, I'll go."

Kau`i was not only concerned about being responsible for the health of the crew during a voyage far from land, she also worried about her two young children. How would they deal with her absence for such a long time and could she endure the separation herself?

"I spent about a year preparing them - maybe I should say preparing us - for the voyage. We talked about how important it was. I told them that I would be safe. They said, 'Okay.' Then they asked, 'How long?' I told them five weeks."

Here Kau`i pauses for a moment considering her children, obviously missing them.

"It's difficult. I know they are being well cared for and I know they understand the meaning of the voyage. They were in the Hawaiian immersion program for a long time and so maybe they even understand it better than I do. But I just can't help worrying about them."

To prepare for her anticipated role as both Hokule`a's only health care provider and as a crew member, Kau`i stepped up her regular regime of paddling and read about the medical problems she was likely to encounter aboard the canoe - heat stroke, dehydration, common illnesses and various psychological issues which she subsumes under the heading of "cabin fever." She now feels well prepared for any eventuality but, as it turned out, the responsibility of caring for Hokule`a's crew will not be hers alone. A few months ago, Dr. Ming-Lei Tim Sing also joined the crew.

"That was actually a great relief for me," Kau`i says. "We make a great team and I'm much more secure now that we can handle any problems we might encounter."

In January, 1999, Kau`i remembers attending the first meeting for crew members at the Maritime Center.

"Bruce and Chad explained the goals of the voyage and of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, and I became even more excited about going. They talked about the opportunity for them to pass on the knowledge they have gained to the next generation of sailors and to do something that our ancestors had done centuries ago. And then I thought about my own children. I realized that I'm not making the voyage just for myself but also for them. When I come home, I will certainly have learned something that I can pass on to them."

CREW PROFILE

Kahualaulani Mick

Tahiti - Hawaii 2000

By Sam Low

Kahualaulani (right)

When Kahualaulani Mick was only four years old, in 1975, his mother took him to see Aunty Emma DeFries, a descendant of Kamehameha I and Queen Emma who was Kahu of a well known educational halau specializing in teaching Hawaiian culture.

"It didn't matter to her or not if you had Hawaiian blood," Kahulaulani says, "she would look into the soul of each prospective student to see if they were open to her teaching. Even though I am not Hawaiian - she took me into her halau and now, looking back on it, that was a turning point in my life."

For five years, every Saturday, Kahualaulani met with Aunty Emma and her other students in an apartment at Queen Emma's summer palace where she was a custodian.

"She took us all over the islands and she taught us a lot about Hawaiian culture and history. Although she passed away in 1980 I still talk to her. My decisions in life are still based on her teachings. “Among Aunty Emma's gifts was Kahualaulani's name which she translated as "fruitful branch of Heaven."

After graduating from Kalaheo High School in Kailua in 1989, Kahualaulani went to Colorado State College in Fort Collins to study Animal Sciences. He lasted a year. "It was too damn cold and the surf was terrible," he jokes about it now, but mainly like so many young Hawaiians who travel "away" to school - he missed the islands.

"They put me in a dorm with three other Hawaiians and all we did was talk about home. When people found out we were from Hawaii they always asked us 'why are you here?' After a while I asked the same questions and, when the first year was over, I came home."

The next year he enrolled in the Hawaiian Studies program at the University of Hawaii to "make up for lost time. Being away led me to really appreciate being Hawaiian," he explains, "and I think my decision goes back to the influence of Aunty Emma."

In 1990, Kahualaulani first joined the Protect Kaho’olawe `Ohana and since 1992 he has attended every one of the annual Makahiki celebrations there. "Aunty Emma was one of the advisors to Emmet Aluli and George Helm in the early days," Kahualaulani remembers, "and I think she knew I would one day become a member of the `ohana. She had Ike Papalua - foreknowledge. It’s hard to explain but even though so many years have passed I feel like she's right here. The day she passed away, a night heron came and perched on a wall at our house in Kailua and so the heron has become a kind of family aumakua. I always associate Aunty Emma with that beautiful bird."

Kahualaulani took the first navigation course taught by Chad and Nainoa and made his first voyage on Hokule’a in October of 1994 on an interisland trip to Moloka`i. In 1995, when Hokule`a went into dry dock, Kahualaulani showed up to help. Later Dennis Kawaharada asked him to be a teacher in PVS' ho`olokahi program.

"That was a really different experience," he recalls, "I was really green. I thought, 'I can't do this, I don't know enough,' but somehow I did - and being a teacher taught me a lot."

For three months that year Kahualaulani virtually lived on the porch of the school at Honaunau on the Big Island - teaching in classrooms some of the time and on the decks of the voyaging canoe E`ala the rest. During 1997, he voyaged aboard Hokule`a for five months during her statewide sail.

"We made connections with so many people. I could see it in their eyes when they came aboard. They all felt the same thing as I did when I first stepped on Hokule`a's deck, a sense of awe - pure and simple - a sense of beauty."

In addition to voyaging aboard Hokule`a, Kahualaulani has spent a great deal of time sailing with Makali`i and her `ohana. "I really like being on Makali`i too," he says. "She's a different canoe and I learn a lot being aboard - and the Makali`i family is wonderfully supportive. I'm honored to think I may be a part of it."

"I remember the first day of the navigation class at U.H.," he says looking back to the beginning of his experience with voyaging. “Nainoa came in and told us that navigation was not about sailing - it was about life - about having a vision of where you wanted to go and making good decisions. I knew then that studying navigation and sailing would change my life, and it has."

Now, facing his first long voyage aboard Hokule`a as apprentice navigator, Kahualaulani admits to being "somewhat scared. But I'm going anyway. I've studied for this trip for five years. I've been teaching navigation and now this is my chance for validation - to actually do it, not just talk about it."

Of the five separate legs of the "voyage to Rapa Nui" he feels extremely honored to be on this one. "There are three reasons why I wanted to be on this leg. First- it's an ancient voyaging route; second - it's the trip that all my mentors made when they were just starting out - guys like Nainoa and Snake; and finally, we will be going home to Hawai`i."

The Sixth Tribe of Tai Tokerau

On November 15th of 2014, Hokule’a and Hikianalia (replicas of ancient Polynesian voyaging canoes) will return to Waitangi in Aotearoa (New Zealand) to celebrate the joining of two seafaring tribes. What follows is the story (in three parts) of the first voyage to Waitangi and how the Hawaiian crew came to be the sixth tribe of Tai Tokerau, as told by Hokule’a’s navigator Nainoa Thompson. He begins in 1980, after his first trip navigating Hokule’a from Hawaii to Tahiti, as his ancestors would have done, without charts or instruments.

The Sixth Tribe of Tai Tokerau – Part One - Preparations

“In 1980, when we returned from the voyage to Tahiti, we took Hokule'a to He'eia Kea, to a little inlet in Kane'ohe Bay. The voyaging community was small and after the trip we were exhausted. We went back to our own lives. In He'eia Kea there is a lot of fresh water in the ocean and a lot of rain, and some of the wood on the canoe began to rot. It was just total neglect by all of us. Finally, Wally Froiseth, a master woodworker who has contributed for years to the revival of canoe-building in Hawai'i, got up at a meeting and said, "We've got to take care of the canoe."

So we went to He'eia Kea and hauled the canoe out of the inlet. There was a lot of growth on her hulls, and the shrouds and stays were all slack. The canoe was an absolute mess. When we finally set sail, the mast snapped because it was rotted. We took Hokule'a into dry dock.

Hokule'a was really built to sail just once-in 1976-for the Bicentennial of America celebration. We went again in 1980, to see if we could navigate by ourselves, to live our culture, and to honor Eddie 'Aikau. We received invitations from a lot of people in the South Pacific who heard about Hokule'a and wanted us to visit them, so we sat down and said, "Let's sail the migratory routes that our ancestors must have taken to colonize Polynesia." And so we started planning for the Voyage of Rediscovery ... rediscovering ourselves.

We mapped out a two-year voyage with seven major legs that reflected the migratory and voyaging routes of ancient Polynesia-Hawai'i down to Tahiti; Tahiti to the Cook Islands; Rarotonga down to Aotearoa; Aotearoa up to Tonga and Samoa; then against the tradewinds from Samoa to the Cook Islands and back to Tahiti-the west-to-east migration route that Thor Heyerdahl said couldn't be done; Tahiti up to the Marquesas; and finally from the Marquesas back to Hawai'i. The entire voyage would cover 16,000 nautical miles.

Crossing 1,700 miles from Rarotonga to Aotearoa, even though it's shorter than the trip from Hawai'i to Tahiti, would take Hokule'a into the tropics and the subtropics for the first time. I thought this would be the most dangerous of all the legs on this voyage. We were going into much colder water and much more complicated weather systems. From the beginning of November to the end of March-the Southern Hemisphere summer-hurricanes spawn in the Coral Sea, come up hurricane alley, through Tonga and Samoa, and head to the southeast. They cut right across the planned path of the canoe. They are infrequent but they do visit the North Island of Aotearoa. But there were advantages to sailing in summer. High pressure systems settle in and that's what you want, you want to be north of the high pressure center where you find trade winds. From Rarotonga we would sail west-southwest, so we needed trades.

So, in the summer the winds are ideal, but you get hurricanes. You don't want to go in winter because westerly wind bands move north and you're sure to get a head wind-hammering and cold-spun off from subtropical low pressure systems.

We wanted to leave before the summer hurricane season and after the winter westerlies die off and the trades fill in, so we decided to sail in the springtime.

We took two years to plan. What would the strategy be? How were we going to navigate this route without instruments? Between Rarotonga and Aotearoa is a group of small islands called the Kermadecs. If we could find these islands along the way, we would know where we were. From there, instead of navigating 1700 of open ocean, we would have to navigate only 450 miles to Aotearoa.

Aotearoa is much father south than Hawai'i, so the star patterns relative to the horizon are very different, and the navigational system we had been using doesn't work as well that far south. The farther you get from the equator, the less available for steering the stars around the north and south celestial poles become. When you go far to the south, the northern stars are below the horizon, the southern stars never rise and set, and the paths stars take in the sky get more and more horizontal. Steering by the rising and setting stars becomes much more difficult. The stars rise in their houses but then veer off sharply as they continue to cross the sky, so once they are up in the sky, it's hard to tell where they rose from and where they will set on the horizon.

I needed to go and study those star patterns. I knew from a scientific point of view that I had to train this way; but I also wanted to visit this land to get an instinctual feeling about it before trying to go there on the canoe. The only person I knew in Aotearoa was a man named John Rangihau, a man who possesses great mana-like one we would call a kahuna. I said to him in my kind of foolish innocence, "Mr. Rangihau, I need to go to Aotearoa, and I need to study the stars in the northern part of your island. I looked at a map, and I found a place called Te Reinga. It has a lighthouse. Can you pick me up and drop me off there? I'll live in the lighthouse; I'll take my own food. And when I'm pau, can you pick me up?" I had no idea what I was doing. I knew no one but him. And he said, "Okay, I'll do that."

So I flew to Aotearoa. I was 29 years old. I went through customs and no John Rangihau. All of a sudden I saw a very friendly lady with a banner with my name on it. She was waving it above her head. We went outside in the parking lot, and she put me in the back of her car. She had a comforter and pillows there to make a bed. And this was just one of the many, many gestures of caring shown to me while I was there. I was thinking, "Okay, we're going to Te Reinga," but when I mentioned this place, she said, "Oh no, we're going to Mangonui."

We we got to Mangonui, there was no house-just some tents and two caravans (trailer homes). It was Hector Busby's land, but I didn't know that. There was a place being excavated; I learned later it was for the foundation of the house Hector was planning to build.

(A little later, Nainoa was introduced to Hector who tested his knowledge of the stars by asking Nainoa to point north. Having passed that test, Nainoa went up on a grassy hill to study the stars. At about midnight, he returned to Hector’s camp to wish everyone a Happy New Year.)

Hector was sitting by the campfire. Suddenly he got up and began to orate in Maori. I didn't know what he was saying, but I could see in the yellow light from the lanterns tears streaming down his face.

When he finished he said, "In this land, we still have our canoe buried. In this land, we still have our language and we trace our genealogies back to the canoes our ancestors arrived on. But we have lost our pride and the dignity of our traditions. If you are going to bring Hokule'a here, that will help bring it back. Whatever you need to do, I am with you all the way."

From that point on, all during his vacation, Hector drove me to places where I could study the stars. We drove a long distance to Te Reinga, the northern tip of the island. The beach there was ninety miles long. We went to the lighthouse, and from there, I could see the horizon to the east, west, and north. At night, I would study the stars and Hector would sleep in the car. At dawn, he would drive back while I would sleep in the car.

At the lighthouse, there was a cave where a pohutukawa tree grew – the same as our 'ohi'a lehua. In the myth of Kupe, the navigator who first discovered Aotearoa, the sailing direction to Aotearoa from Hawaiki-the homeland-was to steer to the left of the setting sun in the season when the pohutukawa blooms. That is late spring, early summer in the Southern Hemisphere, when our voyage was scheduled to depart. And like Kupe, we would leave from Rarotonga.

Te Reinga is a sacred place. When a Maori dies, his spirit goes there to dive into the sea and return to Hawaiki, to the home land. All of these myths and Maori language and oration were new to me. The first time I ever participated in a Hawaiian ritual was when Hokule'a was launched in 1975. When I first got to Aotearoa, I didn't understand then that these myths could provide valuable information for the voyage-I was there to study the stars.

When my studying at Te Reinga was over, Hector took me back to the Bay of Islands. He drove off in tears.