El Porvenir

El Porvenir means "the future" in Spanish.

This is a city in the making. This photograph was taken in 1968 when Mary Jane Cotton (my first wife) and I visited El Porvenir to conduct research for my Harvard Ph.D. thesis. We have not returned - but I would guess that by now the settlement must stretch to the distant mountains and these simple adobe houses are probably all built of "material noble" - brick. The families who lived here in 1968 had moved down from their homelands in the high mountains - seeking new jobs and education for their children - seeking "el porvenir" in a modernizing and industrializing nation.

******

It is hot and windless. In stands of sugar cane on one side of the road that runs from the Peruvian coast up into the Andes, the leaves are not moving. The newly irrigated earth gives off a rich scent which rises over the cane like an invisible aromatic mist. On the other side of the road, a squatter settlement spreads into the desert, a monochrome cubist painting, thousands of houses, mostly of adobe - mud brick.

El Povenir - "the future."

We turn into the settlement and bounce over an open sewer. A cloud of dust rises behind us. In the distance to the left, a steep bluff funnels the houses into the desert as far as the eye can see. A hill surges to the right, a wave of mud solidified by the heat. Anxious about traveling too far from the main road, I turn and head toward the hill. Perhaps that is the place.

A soccer game is underway in the street ahead of us. As I slow, a group of men lurch from a tiny taverna and, carrying their bottles of beer, emerge into the sun to regard us - tattered and patched trousers, tee shirts, unshaven - men without work. The soccer players move out of the way and watch us pass, sullenly but not without interest. My wife beams encouragement as I continue up the hill.

“If we’re going to live here we might as well have a place that looks down over everything,” I offer.

She nods.

I wonder what we have gotten ourselves into.

Thus begins a year and a half sojourn in a Peruvian squatter settlement. My wife, Mary Jane, and I came to El Porvenir as fledgling anthropologists. Our mission - to study a phenomena called “social space” - how the patterns of our settlements express invisible cultural values. The experience would teach us a profound lesson about the meaning of “home.”

In El Porvenir, as in other third world squatter settlements, “home” is a place for starting over, an investment, a workshop, part of an extended family community and, ultimately, an arena where urban forces pry at rural bonds.

Home is:

A new start. Most of the squatters have come to the provincial capital of Trujillo from tiny farming towns in the Andes. In El Porvenir, they begin remaking themselves so they can succeed in a more complex urban-industrial way of life.

A savings bank. Slums are places where people become victims, not the least of landlords who siphon off funds needed to succeed in a new way of life. In the barriada, each home is built by hand and represents an investment of labor that insulates its residents from external shocks (such as rent increases) while also providing the security of investment.

A workshop where mini enterprises are begun. Many homes in the barriada are occupied by carpenters, mechanics, panel beaters, shoe makers. Here they employ about 20% of their neighbors in tiny capitalist enterprises, providing a relatively secure livelihood.

A social molecule in a larger social world. Barriada squatters simply occupy their land, often in large family groups. They build family compounds, tiny neighborhoods of related people who provide a profound sense of security, warmth and mutual assistance.

An expression of self. Like all homes, those in El Porvenir, express the individuality of their owners. But in El Porvenir, a more subtle human drama is at work. Urban forces decay rural bonds - stimulate a sense of self over communal interest and loosen the ties of blood. Community breaks down as some families, the most successful of the barriada, move away.

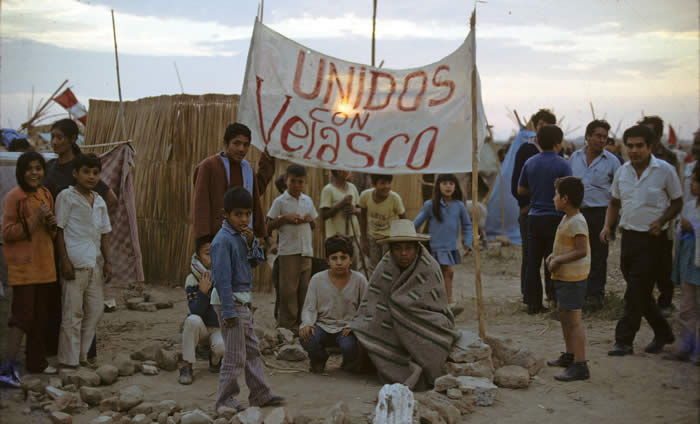

Unidos con Velasco

In 1968, General Juan Velasco Alvarado took power in Peru in a coup. These people

have recently "invaded" vacant land near El Porvenir to stake out their homesites

and by their banner are seeking support of the central government.

Our approach to the squatter settlement was at first circuitous, cautious. The popular press depicted El Porvenir as dangerous, a den of thieves, communist sympathizers, drug lords and their henchmen. The few anthropologists who had ventured into such squatter settlements had assured us that these stories were all lies. Still, we were anxious. Was it really safe? Would we be accepted? How should we choose a family to study? We solved this last problem by almost literally dropping in on the people who would host us for our year long stay.

At the end of a long day of aimless driving through El Porvenir, we parked our Volkswagen beside a dirt track that led up onto a steep hill and we trudged up a narrow path toward the summit. Halfway up, we came upon a series of curious earthen platforms that appeared to have been excavated into the side of the mountain. I decided to venture out on one of them. As I reached the middle of the platform, the earth began to tremble. "An earthquake," I shouted to my wife as I began to retreat toward her. Simultaneously, from beneath the platform, an elderly couple appeared followed by swarms of children.

"What are you doing on our roof?" they demanded.

Roof? I suddenly realized that the "platforms" were actually the flat earth-covered roofs of a row of houses directly below us. I had almost fallen through the one that belonged to the couple who were now my inquisitors. Not knowing what else to say I stammered, "we are looking for a place to stay."

"By falling thought our roof?" they replied, laughing hilariously. "Come on down."

Their invitation was extremely gracious, I thought, given that we had almost plummeted into their parlor.

In their adobe house overlooking El Porvenir, we met Senor and Senora Pastor and promptly abandoned any pretense of scientifically selecting our "informants," as anthropologists call those who participate in their studies. Within a week, we had moved into a house owned by the Pastors' cousin, Alfredo Vasquez Jara.

Senor Jara lived in the midst of a large extended family of fifteen households, including the Pastors on the hill above him, who had all migrated from tiny towns surrounding the larger center of Santiago de Chuco in the lush Peruvian highlands. Don Alfredo is a short muscular man, lantern jawed, with clear green eyes under a shock of black hair. On our first day of residence, he returned from work as a waiter in a Chinese restaurant to welcome us.

"So, you are an anthropologist," he said, grinning with good humor. "I guess then that you have come to study us? Let us begin."

Alfredo's story unfolded slowly. He told me that he came from a poor mountain family. By the age of sixteen he had worked as a farmer, trucker, plantation worker, miner and assistant to a trader who carried merchandise throughout the high sierra on mule back. He had received an education only through primaria, the third grade, but was an avid reader. What he read filled him with a lust to live in the city, "to know modern life," as he put it. By 1956, when the "invasions" began ("invasion" is a word used by the squatters to describe their illegal occupation of government land), he was married and living in a slum in the coastal city of Trujillo. For the next two years, Alfredo and hundreds of others attempted to squat on vacant desert on the outskirts of Trujillo. But as soon as they erected their rude shacks of woven mats, the military bulldozed them down. In 1957, with a change of government policy, the bulldozing stopped.

"Oh, you should have seen the run on this place then," Alfredo told me as we sat in the "parlor" of our shared house with the constant chatter of our neighbors spilling in through the unglazed windows. "Within one night, with the dawn, the whole place was full of shanties. What an invasion. More than two hundred houses had sprouted in the desert. After that, they couldn't make us go away. The whole thing was like an explosion, an explosion of people!"

By 1958, El Porvenir had grown into a small town of more than 10,000 inhabitants and Alfredo had staked out his lot of land next to a cousin on the hill.

"I climbed up the hill with my wife and we looked the place over together," he told me. "The land was filled with tremendous boulders, cliffs of stone. 'Look at the size of those boulders,' my wife said. 'Never mind,' I told her, 'I will dynamite them.' So I started, I dug out the holes for the charges and we dynamited the rocks out. Every night, I walked from Trujillo to work on my lot. I carried my pickax on my shoulder. The moonlight was like daytime. It was early, very early. I'd arrive and I would sit on a big rock and listen. Silence. Nothing. Then I would start working with my pick, working alone, until slowly, day by day, I made the platform for my house."

I recorded Alfredo's stories at midnight, when he had returned from work, in the "parlor" of the house we rented from him. Next door, across a steeply pitched path that led up to the second story where Alfredo lived, was our bedroom. These two rooms sat on his "platform," sixty feet long and thirty feet deep, eighteen hundred square feet of level land hewn into the hillside by four years of unvarying labor. From seven in the morning until seven at night Alfredo worked as a waiter in the Gallo Rojo restaurant. Then he hung up his apron and went home to sleep until wakened at midnight to trudge the two miles out to El Porvenir. With the dawn, he returned to his room in the slums to wash and dress for work. In 1962, Alfredo and his wife moved into their first house on the hillside. They had little money so it was a simple shelter of woven mats tied to upright poles and roofed with more mats.

"In the bedroom, I set up three cots. One for my wife and me and one for the two children we had by then. Three cots. We were comfortable. We were fine. In the corner, my wife had her stove and there she cooked. When it rained, the water came through, but what did it matter? We got up and covered everything with a piece of plastic and waited for the rain to end. It doesn't rain much here so those incidents passed quickly, We forgot about them. The wind kept coming in, but then we sewed cardboard to the mats so that when the wind blew it wouldn't pass through."

********

Celso Gutierrez (left) Alfredo Vasquez Jara - our landlord (right)

The people of El Porvenir work at various jobs, usually six days a week. Celso Gutierrez (left) is a zapatero - a tailor who works in his home. Alfredo Vasquez Jara (right) is a waiter at El Gallo Rojo, a Chinese restaurant in the nearby city of Trujillo.This photograph was taken on a Sunday - a day of rest and, often, of singing and social drinking.

These are more typical photographs of Celso - working at his craft with a sewing machine turned by a foot-operated treadle.

Oscar Alcantara and his compadre Gilmer Pastor work together to add a new room

to Gilmer's house. The residents of El Porvenir pay no mortgages,

instead, they save money for building materials and construct

their house themselves with collaborative labor, as they once did

in the highland communities from where they came...

The adobe bricks are made from dirt that must be imported into the community

because the land all around is mostly shifting sand...

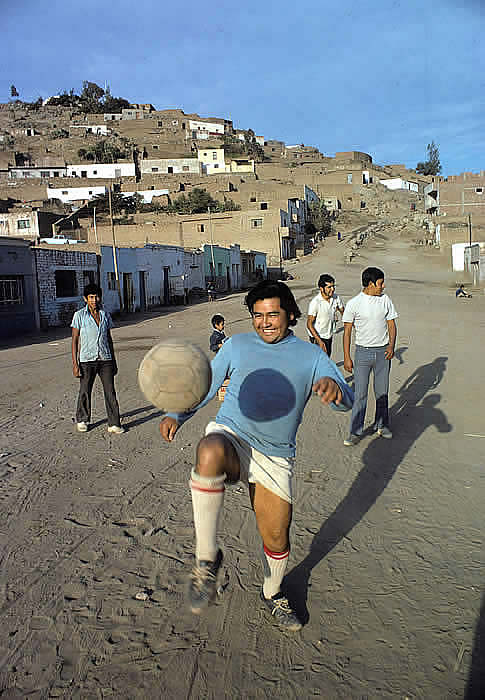

Soccer is a passion - played in the streets and nearby vacant fields.

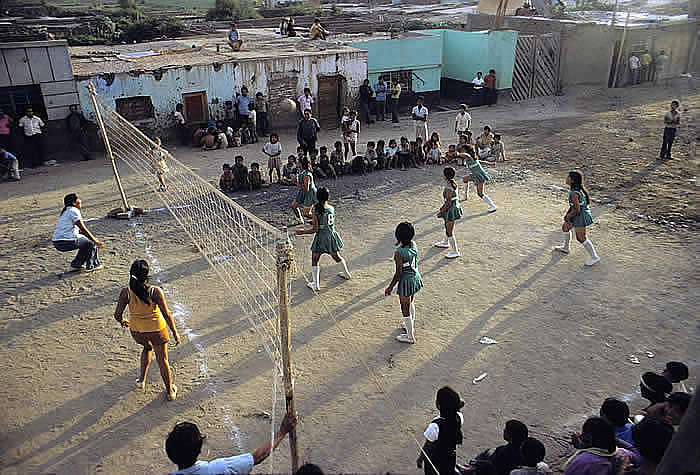

Girls from the settlement play volleyball

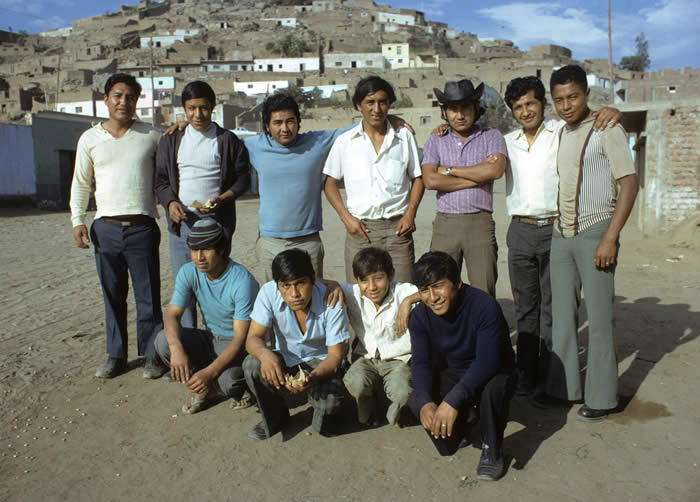

Boys and young men from the neighborhood.

Children from our local neighborhood - the true el porvenir

of the community.

Funeral - one of our neighbors has died. There is no hearse, we carry

the diseased to the burying ground, a hole in the nearby desert.

Settlements like El Porvenir are literally carved out of the desert by the sweat of their residents. In a sense, these are "new towns" - as architects like to call such places - but they are created not by architects and planners and bureaucrats - but by the people who live in them.

At the time of our one-and-a-half year residence in El Porvenir, many regarded these settlements as lawless slums. We found the opposite - a well organized community in which people went about their daily lives without unusual fear of crime. El Porvenir was a place of established and loving families, of industry and hard work.

More Photographs to come - this section of my web site is under construction.