The Vineyard Gazette

Friday, August 19, 1960

Port Hunter, Ghost Ship Sixty Feet Beneath Tides

is Visited in Exciting Venture of Young Divers

by Sammy Hart Low

Dick Jones, Sam Low and Willie Jones display objects salvaged from the Port Hunter

Port Hunter

Arnold Carr, Willy Jones, Dick Jones and I located and explored the wreck of what once was the Port Hunter - a proud British freighter that went down off Hedge Fence in 1918.

After constant nagging, I was able to persuade my father, Sandy Low to take us out to the site of the wreck in his boat. We all convened in Harthaven at 8 o'clock on Sunday morning and started to arrange our gear. We seemed to be overloaded with equipment but agreed .that it was better to be safe than sorry. Our gear consisted of six compressed air tanks, four rubber suits, grappling hooks, plenty of rope, two buoys and all the other apparatus needed to explore the wreck once we had found it.

Ready to Shove Off

We finally were ready to shove off and as we swept out of the harbor we all wondered what was in store for us at our rendezvous in the tricky waters a mile and a half off East Chop. We were very doubtful that we would ever find the wreck because we only had rudimentary equipment with which to locate the exact position of the sunken ship. We knew that we would have to pinpoint the location of the freighter before we dove because there was very little chance of finding it if we had to use underwater search methods. All of us knew that if we were off our position by only a few feet we would probably never locate the ship in the cloudy waters that prevail in this area.

Within a few minutes we had passed East Chop and taken up our compass course to Hedge Fence and, we hoped, the Port Hunter. We arrived in the vicinity of the wreck, which was marked by violently swirling waters and many whirlpools as the current ripped across the shoals. After taking a few bearings, we dropped a buoy over the side to mark the approximate position of the freighter. To our chagrin, the fifty foot rope attached to the buoy paid out all the way without hitting bottom. Since our charts indicated that the ship was lying in forty feet of water, we promptly retrieved the buoy and commenced to make some soundings. We found the water to be very deep and quickly realized that we were not in the vicinity of the wreck but about a quarter of a mile west of it.

We decided to .make a few passes over the area with the grappling hook to see if we could snag the wreck's superstructure which was only about ten feet below the surface. After two unsuccessful passes, we began to wonder if the whole effort wasn't futile. No one wanted to leave, however, and so we decided to make a third pass over the area.

We had attached a buoy to the end of the hook, which we could throw over the side in case we snagged something. Willie was holding the rope to the grappling hook while Arnold held the buoy over the side, ready to throw it overboard. After the first two passes, we all seemed to become pessimistic and Dick, Arnold, and I stretched out on the engine cover to take a sunbath. Willie stood to his post, however, but was not in an advantageous position if the hook happened to snag something. Arnold had stopped holding the buoy with his hand but had propped his foot up against it in such a manner that it would not fall overboard, but a sharp tug would pull it into the water.

"I've Got Her"

The boat drifted steadily to the west and we once more approached an area of great turbulence which my father thought marked the area in which the Port Hunter lay. The sun was affecting us all and we were unprepared when the rope was wrenched from Willie's hand, and he cried out, "I've got her". Arnold was taken by surprise and jumped up with a start, just in time to see the rope to the buoy part and disappear below the surface of the water. It had become snagged on a rod holder and when the grapple caught on the obstruction, whatever it was, the line had parted.

Pandemonium reigned as we all rushed to the side of the boat to see where the line had disappeared. Promptly, we threw another buoy in the water, only to discover that the line was still too short and the swift currents were carrying it away from the scene. My father quickly maneuvered the boat up to the runaway buoy and I snatched it up with a boat hook.

Willing hands tied a longer piece of rope to the anchor as the boat was maneuvered into the general area in which we had lost the grapple. With a heave, she was in the water and soon bobbed to the surface, a definite reference point for our underwater search. Much to our disappointment, the buoy soon sank out of sight as the powerful currents forced it under the surface. Once more the boat was maneuvered into the general area and I took up a position on the bow to try and spot the submerged marker.

As I looked to port, I saw a faint trace of yellow and I knew that we had found it. Dick quickly threw in the anchor and we all settled down to wait until the currents reached their lowest velocity. Unfortunately, I am not a very patient person and quickly found that the two hour wait ahead of us was not well suited to my temperament. I fidgeted and fussed with my equipment and pestered the other divers with my constant questions until I was told to be quiet by the rest of the crew, who outnumbered me. I was quiet, but not calm, for the rest of the time.

Buoy Came to Surface

Soon we could see that the current was abating and to our great amazement the buoy came to the surface about a hundred feet from where we were anchored. Arnold spotted it first as it popped to the surface and then quickly disappeared. It seemed to be playing hide and seek with us as it bobbed up and down, but soon it rose to the surface and exposed itself, amid our jubilant cheers. In my usual hurried manner, I pulled on my rubber suit, put on my aqualung, strapped on my weight belt and adjusted my fins and mask. I was the first to be ready and had to wait for my friends as they donned their equipment in the careful and methodical manner that experience has taught them is the best way. Arnold was soon ready, however, and we flopped over the side together.

Sam descending to the wreck

I had brought a spear gun along as protection but promptly I got fouled up in the string attached to the spear. After untangling it, I passed the gun up to my father and asked him to take the string off, which he did, and handed the gun back to me. I knew that the gun would have no effect against a large shark but I felt better having it along with me.

Arnold beckoned to me as I grabbed the anchor rope and began to descend. The water around us was murky and our vision was restricted to about ten feet. At about forty feet my ears began to hurt and I hung suspended from the anchor rope, trying to clear them. Arnold had already gone down, I could see his bubbles slowly passing upward from some position farther down the line. After a few minutes, I had cleared my ears and started to descend. There was no sign of the other divers who were supposed to follow us.

Sandy but Hard Bottom

A few feet farther down I could see the green of Arnold 's tank and hear the regular cadence of his breathing. He waved at me and together we descended to the bottom, a depth of fifty feet as indicated on his depth gauge. We landed on a sandy but very hard bottom In which were embedded small pebbles. In front of us there was a trench which sloped off into blackness. We cautiously approached the perimeter of the crater and began to slowly descend. When we reached the second bottom, Arnold 's depth gauge indicated sixty feet, the deepest depth we had penetrated. The water around us was very dark, most of the sunlight having been filtered out by the matter suspended in it.

We swam slowly forward, not knowing what to expect. After a few yards, we turned towards the south and proceeded cautiously. To our glee, we came upon the anchor of our buoy and knew that we were very close to whatever had snagged our grappling hook. Arnold and I swam in a southerly direction, fully enjoying the sensation that every diver experiences when he is cut off from the force of gravity, suspended in the friendly matter from which our ancestors were spawned.

I could see something ahead. Arnold had seen it also and increased his speed at the same moment I did. We came upon a mass of twisted cable embedded in the sand, its exposed curls leaping out from the sea's bottom and resembling a giant eel. I screamed with delight when I saw a large cement block ahead, which I took to be an anchor used by one of the salvage ships that attempted to save something from the twisted wreck which must lie nearby.

Something Enormous Nearby

Arnold beckoned to me and we swam forward about twenty yards until we realized that something was wrong. We could both sense the presence of something enormous nearby, although we had not seen anything yet. Very carefully, we swam forward until ahead in the misty sea we could see the dark form of something very large. I looked up and could see a shadow disappearing into the translucent sea that surrounded us. Slowly, we inched forward toward the ever darkening patch of water that loomed ahead of us. I cannot describe the true impact of what I saw, let it suffice to say that I have never seen anything so mysteriously beautiful and exciting as the dark form that confronted me there, sixty feet beneath the surface of the ocean. I extended my spear gun and pointed it in front of me as I slowly inched forward. I was awed at the sight before me and could not believe that we had found the wreck so easily. My spear touched something solid. I jabbed at it. The unmistakable hollow sound of steel rang dully there in the sea.

Both of us jumped forward to caress the bow that stretched up above us as far as we could see. We screamed for joy and shook each other's hand in our wild delight at having found the wreck and in such good condition. Arnold and I swam upward slowly, our ears screaming with the release of pressure as we rose. The bow of the freighter was well defined and rose for about thirty feet. The whole ship was encrusted with some sort of brown sea growth, but the plates and anchor port of the freighter were still clearly defined. It was a clean wreck! I couldn't help thinking that this was all a dream in which I was reliving the exploits of Cousteau that I had seen many times in the movies and read about in his books.

Railings All in Place

We reached the deck and immediately saw that the railings were all in place and distinctly outlined against the light hue of the surface. As we swam slowly down the deck, which listed about fifteen degrees to port, we were both overawed by the wonderful adventure that we were experiencing. A winch loomed up ahead of us, most of its details well defined. Carefully, we swam towards the stern, marveling at the variety of fish that dwelt in the jagged crevices amid the rusty plates. A piece of superstructure soared up out of the darkness above us as we swam toward the port side of the ship.

All the doors had been blown away, either by the action of the pressure or by the force of the swiftly moving currents that are common over Hedge Fence. We swam carefully into one of the doorways, making sure that our fragile air hoses did not snag a piece of the jagged wreckage. We had entered a small room with four doorways, one on each side. I swam through one of the openings and headed toward a section of the starboard railing. Easily, I flipped over the side of the great ship and swam down the starboard side, inspecting its rusty hull. I touched bottom and slowly rose back to the level of the deck.

Arnold was swimming slowly toward the stern, his bubbles trailing up behind him and his regulator making a sharp whine as he sucked air into his lungs. I caught up with him and made a motion toward the stern of the ship as we swam on into the green haze that surrounded us.

Tautog Swam in and Out

Large tautog swam in and out of the open hatches and lurked in the shadows cast by the twisted wreckage. Smaller fish had taken up housekeeping in the few remaining pieces of superstructure. The fish had taken command of the Port Hunter and seemed to resent our intrusion as they eyed us with curiosity. None of the fish were afraid of us, as they all approached very closely to inspect us carefully with their large glassy eyes. I carried a gun with me but did not want to disturb the beautiful peace that had settled over the dead ship with its almost tame fish in attendance. A dark object rose up ahead and above us as we swam on toward the stern. For a moment, I could not recognize the long cylinder that pointed toward the surface and rose about fifteen feet above the deck, but I soon realized that we had found one of the freighter's smoke stacks. Effortlessly, we swam up the funnel and peered into it from the top, expecting a startled eel to slither out at any moment. We were both amazed at the small size of the stack. It couldn't have been more than a foot and a half in diameter. Arnold raised his hand above his head and pulled it down twice, making a hooting noise through his mouthpiece. We both smiled excitedly at his joke.

I dropped back to the deck and began to peer into its open hatches and gaping holes. We did not expect to find much of the Port Hunter's cargo left, as she had been ransacked by many salvage divers in search of a fast dollar. I found a deck grating, red from rust and corrosion, and peered down between the bars into the hold. Great railroad wheels loomed up out of their sandy matrix, still in good condition although they had been in the water for about forty years. According to reports, the ship was carrying 800 car wheel assemblies as part of her cargo. Each wheel assembly weighs more than a hundred tons! Buried deep in her holds are 2,000 tons of steel billets, unless some of them have been salvaged. Most, if not all of the freighter's cargo of 2,072 tons of clothing has been salvaged.

A Clammy Arm.

I swam over to Arnold, who was inspecting a piece of superstructure on the port side of: the ship. We found ourselves on a square platform, three sides of which were enclosed by a three foot high wall. As I peered into a dark corner of what we believe once was the bridge, I felt a clammy arm encircle my shoulder and squeeze my arm. I turned with a start, to find myself peering into the delighted face of Dick Jones. Willy was wildly pumping Arnold 's hands, emitting small excited squeaks which scared off all of the nearby fish.

All four of us began to explore the ship, heading once more toward the stern. Willie and I swam over the side of the freighter to inspect a large hole that had either been opened by the force of the collision that sank the Port Hunter, or by the dynamite of some salvage diver. I darted forward and looked into the fracture, careful not to get under anything that could fall on me. Willie pulled my flipper, warning me not to go too far in, and swam toward the stern. I rested there for a few seconds, waiting for my eyes to adjust themselves to the darkness inside the ship. All I could distinguish were a few pieces of jagged wreckage.

Suddenly, I felt an oppressive loneliness seize my mind and I quickly swam back up to the deck to look for my friends. Arnold and Dick were ahead of me, inspecting a large gaping hole in the deck. I passed the second smokestack, raked slightly toward the stern and listing grotesquely to port. The air in my tank was getting low as I had to suck hard to get a breath. I knew that I would soon have to go on reserve and come to the surface, so I tried to breathe as little as possible. Arnold and Dick were hanging vertically inside a crack in the deck, inspecting the hold, which contained more railroad wheels. I peered in and scraped my air hose on a piece of the deck, "no place for me", I decided.

Into the Cabins

The three of us swam into what remained of the cabins, inspecting the twisted and corroded fittings that had once graced a sailor's refuge from the howling sea. My air was getting very low. It was becoming increasingly hard to take a breath. I cursed myself for not being more careful of my air supply. Arnold picked up a bottle that he found lying on the floor of one of the cabins, looked at it, and threw it aside. It was a large green bottle with a screw cap. I cast a quick glance at it as we swam out onto the deck once more. Arnold picked something up off the rusty plates and handed it to Dick. I finned over to look at the find. Dick was holding a well preserved brass door knob and lock. The knob was still in good condition and the lock's keyhole looked like you could put a key in it. A piece of rotted wood was attached to the lock assembly, its surface full of holes made by teredos or other forms of marine worms. I could barely take a breath and realized that I must go on reserve and surface. Quickly, I reached around in back of my tank and grabbed the metal reserve ring. I yanked it down and felt the easy flow of air once more. I had five more minutes of air but must not delay my departure. I signaled my situation to Arnold and began to rise through the brightening sea.

Suddenly, I became aware of the throb of large propellers. I was about fifteen feet below the surface but did not dare rise any further for fear that a ship was passing overhead. About four minutes had elapsed and I knew that I would have to surface soon. I decided to surface now so that if a ship was nearby I could submerge once again while it passed overhead. The sound of propellers had not diminished as I started my ascent. Exhaling, I broke surface amid a large circle of bubbles. I spun around quickly, expecting to see a boat bearing down on me from any quarter. There wasn't a boat in sight! I couldn't understand it until I saw the steamer heading for Nantucket , already about half a mile away.

Boat 200 Yards Away

Our boat was riding at anchor about two hundred yards away from where I had surfaced. I rolled over on my back to let the buoyancy of my empty tank keep me on the surface. I aimed toward the bow, feeling the current beginning to pull me away from the boat. I increased my angle on the bow and began to swim faster, the weight of my equipment. pulling me down lower in the water. My mouthpiece was floating in front of me, I grabbed it, thrust it into my mouth, and submerged.

There was not much air left but I thought that I could make better time submerged than on the surface. After about a hundred yards, I ran out of air and was forced to come up once more. The current was pulling more strongly now as I swam the last few yards and seized the rope that we had extended over the stern as a safety precaution. Dad pulled me in the rest of the way and at last I was able to grab the steps which hung over the stern of the boat. After passing my weights and fins aboard, I clambered up the short steps and sat on the stern seat, trying to get my wind back.

After a few moments, I was able to jabber excitedly to my father, trying to relate an hour's adventure in a few seconds. Soon Dick surfaced and started to swim toward the boat. He was having a hard time swimming against the ever increasing current, but at last was able to seize the rope that floated behind the stern. Dad pulled him in and he soon was clambering up the steps.

Quickly but carefully we stowed all of our gear forward and prepared to weigh anchor as soon as we saw the other divers surface. The current was increasing with every passing minute and the others would have a hard time if they had to swim all the way to the boat. After a few minutes, we saw them surface and told them to stay where they were. Dick hauled in the anchor while I coiled in the line. As we approached the divers, I could see that they both had inflated their lifeguards, a portable life preserver which can be blown up by merely squeezing its neck. I was sure they had done this only to help stay afloat while we proceeded toward them, but later learned that Willie's reserve valve had not operated properly and he was forced to come to the surface quickly.

Talking it All Over

We all talked excitedly on our way home, sharing out delight at having located the wreck so easily. During the trip, Arnold called an incident to my attention. When we came upon the coils of ripe in the sand just previous to our discovery of the wreck, I had told him, underwater, that I thought we had come across an anchor used by a salvage boat. He had thought that I said "white duck" instead of "salvage anchor," and was amazed when I nodded after he repeated the two words.

It is very hard to distinguish words underwater and I had thought that he had merely repeated the words “salvage anchor” so I nodded my head in reply. We all laughed at this little incident and shared our various emotions in discovering the wreck. After a short discussion of how far toward the stern each diver had gone, we discovered that none of us had actually reached the stern of the Port Hunter. We had only explored one of the ship's holds and had been through only a part of the remaining superstructure. No one had found the engine room or had penetrated any of the other holds. We had just begun our exploration of the ship and we realized that many more days of exciting discovery lay ahead of us before the winter gales end our diving for the season.

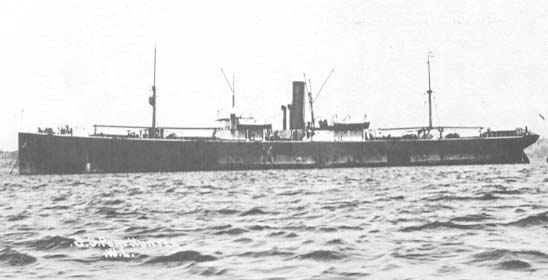

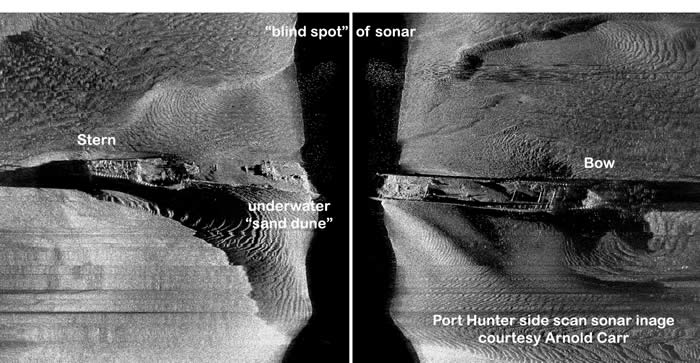

About fifty years later, Arnold Carr who has since become an internationally known diver, researcher and hightech

finder of all things underwater made this image of the Port Hunter on the bottom using side scan sonar

towed from his research vessel.