Sam Low

Just another WordPress site

Back Cove Log

Published in Soundings Magazine

August, 2005

as “Maine Sailor Tried his Hand with Power”

(What were they thinking?)

Article and Photos by Sam Low

by Sam Low

Anchored at Jewell Island

I have to admit my prejudice right away.I like sailboats. Under wind power I have cruised many thousands of miles in contentment – along Maine ‘s foggy coast and among dazzling Polynesian islands. I love the commitment to nature’s rhythms that sailing requires. So I was apprehensive when I took the assignment of cruising favorite downeast grounds in a power boat, but the week my wife and I spent aboard the twenty-nine foot Back Cove surprised us. We came away with some prejudices intact, but discovered that powering offers advantages that cannot be ignored.

_______________

On wednesday, at DeMillo’s Marina in Portland , we need four wheelbarrows to carry our gear – and two more trips lugging our kayaks.

“Holy mackerel,” says Jon Spaulding, Back Cove’s CEO, “this boat is an overnighter and it looks like you’re making a transatlantic crossing.”

Not exactly, but I did plan to use the Back Cove’s speed to range widely. We will power beyond familiar Penobscot Bay waters to cruise further downeast. Machiasport, a 400 mile round trip, is our ultimate destination.

We depart in thick haze, apprehensive about narrow passages between islands and busy harbor traffic. We needn’t have worried, the ship’s GPS plotter – centrally located in front of the helm – shows the way to Jewell Island in Casco Bay .

“What kind of boat is that? She’s a beauty!” comes the call from a sloop as we maneuver to anchor.

“She’s a Back Cove 29,” I answer, “a new design by a company in Rockland .”

“Well,” says my neighbor bestowing high praise,”she looks like the kind of power boat a sailor would like.”

The Back Cove’s sheer is a svelte curve punctuated by a trim cabin that sweeps back to a graceful pilot house with windows all around providing excellent visibility. Her fittings – bow pulpit, rails, cleats, portholes – are of the quality lavished on the best sailing yachts. Below decks, she presents warm cherry joinery to accent the cabin’s sleek fiberglass curves. A table pops up between the vee berths for dining and descends to provide a spacious sleeping platform. The galley is to one side – topped by Corian – the head and shower to the other.

As tenders we’ve brought two small Lincoln kayaks. On this first evening, we glide on still waters listening to gulls’ cries. Seals pop up to examine us with an experienced gaze. Then they lift their snouts and slip backwards into the deep.

On Thursday morning , a nearby fog horn moans. A sailboat departs only to return out of the gloom an hour later, her captain having decided to lay over until it clears. It’s deceptively peaceful but weather reports say it won’t last long. Hurricanes Bonnie and Charlie are racing north from the Gulf of Mexico .

The fog lifts enough in the afternoon to see distant islands. I plan to go to Robinhood Cove, about thirty miles away, and hole up there. In a sailboat, such a trip would mean six hours of windward slogging but in little more than an hour we’re off the Sheepscot River . The waves are four feet and cresting but the Back Cove moves along at 20 knots with negligible effort. Lured by this promise of speed, we pass Robinhood by and head for Round Pond in Muscongus Bay . Taking a mooring for the evening, we paddle ashore to the Anchor Inn – one of our favorite Maine restaurants.

Pemaquid Point

Round Pond is aptly named – an almost perfect circle of water rimmed by modest year-round cottages and the occasional newcomers’ splendid summer home. NOAA weather predicts heavy downpours and fog as Bonnie sweeps across Maine , followed by Charlie. Here in the sheltered harbor it’s peaceful. We think of moving on, but by ten AM the fog creeps upriver, clinging to the cool water. Houses ashore drift from view. The lobster fleet is moored up – slickers hung in cockpits.

“That fog looks pretty thick,” says Karin.

We decide that if the locals won’t go out, either will we. But how will it be to hole up on a 29 foot power boat designed for day trips? We’re about to find out.

I first sailed downeast more than 30 years ago on a 28 foot Eldridge-McGinnis sloop, single handing among fir clad islands for months at a time. I cannot help comparing her to the Back Cove.

Breakfast in the pilot house

Below decks, the sloop enveloped me like a spacious cave. The Back Cove, on the other hand, divides her length like a split level ranch into the cabin and pilot house. At first, I miss the sloop’s comfy main saloon but that changed when we zipped shut the canvas to enclose the pilot house. Karin reads there while I sprawl below on the ample berth – the stereo low – a cup of coffee at hand.

“The only thing I miss is my dog and my fireplace,” Karin says.

The Back Cove is not designed for extended cruising and we’ve brought way too much stuff – but we find places to stow it all. The pilot house has many cubbies, there’s ample space in the lazarette and shelves accumulate the normal cruising clutter. Under the bunks go our duffel bags.

Our cruising range has shrunk with these two lost days. Machiasport is now out of range. The weather forecasts a window of clearing tomorrow so if we’re lucky we’ll get to Criehaven – our planned first day destination – on day three.

On Saturday , after Bonnie’s passage, the skies clear to present pine studded islands and sailboats moving sedately across the glistening Medomak River . Offshore, Bonnie lingers in the form of eight foot swells, sending spray over the pilot house and giving us a lumpy ride. Yet we maintain 20 knots, making Criehaven by two PM .

Criehaven

Criehaven is a time warp to an era before the bustle of yachts and visitors. It’s one of Maine ‘s outermost islands, a fishing village in the truest sense. Lobster gear is piled high on piers. There’s no running water. No electricity. Generators and a few communal wells provide these necessities.

Karin and I walk through the tiny village and across fields lined with wild rose and loostrife, encountering Wyeth houses under Wyeth skies. We enter a Hobbit’s forest by a rutted road ponded with Bonnie’s rain, following a sign that says “Bull’s Cove.” The earth underfoot is springy – the consistency of peat – carpeted with moss and lichen and ferns. A heron hoots in the distance. We follow the sound of surf to the cove and look out at a thickening layer of mackerel clouds descending to the sea.

“Here comes Charlie,” we think – and we turn back to the boat.

All day, NOAA has predicted winds from the southwest but now they decide we’ll get 30 knots from the northeast – right down the throat of Criehaven’s tiny harbor. A clear advantage of a powerboat is the ability to scamper for cover when the weather deteriorates, so we slip our mooring and beat it at 25 knots to sheltered Rockland harbor.

On Sunday morning, we learn that Charlie has taken an unexpected turn off shore. NOAA predicts light winds and clearing skies so I plot a course to traverse Penobscot Bay to Little Cranberry Island and a favorite shore front restaurant – The Isleford Dock.

“We’ll dine out in the style to which we’d like to be accustomed,” I announce to Karin, who – from the look of it – is none too pleased with the prospect of yet another 25 knot dash.

The trip takes us through Fox Island thoroughfare and Merchant’s Row. The seas are slate colored and oily under a monotone sky – as if Bonnie had sucked all the energy with her as she passed out to sea.

Cruising on a powerboat, I discover, is an intellectual exercise rather than a sensual one. The pilot house isolates us from wind and spray. The engine’s beat overwhelms the subtle sound of fog horns and bell buoys. My gaze flicks constantly between the sea ahead and the GPS plotter as Karin barks out landmarks from the chart. Like flying an aircraft at low altitude – the Back Cove requires constant attention.

We duck into Burnt Coat Harbor on Swan’s Island , thread the narrow channel to the east and head toward Little Cranberry. At 25 knots, I swerve through a minefield of lobster buoys. In this part of Maine , the lobstermen use a main buoy and a smaller one, called a toggle, attached to it by a light line. If you pass between the two buoys you’ll foul the prop.

“So far, so good,” I think – just as I pass over a toggle line. I cut the throttle and hold my breath. No luck. The lobster buoy trails behind, twisted around our prop.

A cold wind blows. The ocean is black beneath our keel as I struggle to unwind the lobster warp. “I really don’t want to dive into that dark sea,” I think. Luckily, I am able to untangle the mess, cut the line and tie it off so the fisherman won’t lose any gear. We resume our journey, now chilled to the bone.

Just off Great Cranberry Island , we overhaul a classic picnic boat sedately cruising at eight knots – a relic with a plumb bow, graceful shear and an upright pilot house. Her passengers sit on folding chairs, chatting quietly. We rush by at three times her speed, shivering and ready for a warm seat at the Isleford Dock bar.

Dinner is splendid – eggplant in Sezuan sauce, tuna tartar, calamari, Angus steak, fried onions and asparagus, washed down with a flinty Pinot Grigio.

On Monday, the Isleford lobstermen are up at five loading bait at the Co-op.

Isleford Fisherman’s Co-op

“Fishing is good,” one lobsterman tells me, “but it would be nice if this rain would stop.”

I agree. This is our fifth day on the boat and only one has been clear and sunny.

Little Cranberry is quiet. We walk past trim cottages with dayglow lobster buoys in the door yards and summer bungalows cosseted by gaudy flowerbeds. A few folks drift past on whirring golf carts. Wood smoke perfumes the island with the scent of fall.

Back on the boat, we see Mount Desert humped against the horizon like a stranded whale. The sky is mottled steel, the ocean flat and unsullied. Sailboats motor past under bare poles. We decide to sightsee. We spend the day visiting Bass Harbor and Mackerel Cove – then motor on to a dinner engagement with friends at Isle au Haut .

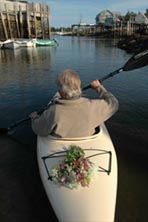

Paradoxically, the possibility of speed induces lassitude. Unlike cruising under sail, there’s no need to get under weigh at eight – or nine – to make a distant landfall. So we don’t. On Tuesday morning, we enjoy the ritual of preparing breakfast and dining in our pilot house with a view. Then an exploratory paddle with our kayaks, writing in our journals and reading. After a hot shower we’re off to Matinicus, our last stop before heading home.

Matinicus Fish Shack

On Wednesday, the sun rises over Matinicus harbor behind a pink scrim of fog. The ring of a bell buoy joins the cry of gulls and the cough of diesel engines in an early morning chorus.

At low tide, fishermen’s shacks stand tall on barnacled stilts. This is our last day – an eighty mile dash to Portland awaits us as we sip our morning coffee and chat with folks moored close aboard.

We make the run into a headwind and choppy seas. We cruise at 22 knots, throttling back to 17 when the seas pile up in front of us. This is not fun. The roar of the engine and glint of ocean takes it toll. When we enter the channel to Portland Harbor , we’re tired and ready for lunch at DeMillo’s.

_________

So what’s the verdict? I have to admit that I missed the sensual process of voyaging under sail – attuning myself to changing wind and current, the breeze on my face, the acute awareness of sound all around – whooshing wake, bell buoys, moaning fog horns. But sailing takes up most of the daylight hours. Arrival at day’s end is a time for mooring and furling sails, a glass of wine and watching yet another stunning sunset. Many sailors set out early in the morning, needing time to make another destination. The Back Cove allowed us to make tracks from one anchorage to another with plenty of time for long walks ashore or seaborne probes in our kayaks. She encouraged reconnaissance – poking into anchorages we had never visited, moving quickly to yet another – bumblebees sampling nectar from many wide spread gardens.

Kayaking at Matinicus

We also discovered the joy of poking along at seven knots like picnic boats of yore, our engine a gentle hum, the fir studded islands gliding by, a cup of tea near at hand. The unexpected thing about speed was the ability to choose when – and where – to go slowly.

As a sailor, my first impression of the Back Cove was that she’s reckless with time, compressing distance in a way that was hard to get used to. But eventually she became just another boat. Not a sailboat. Not a powerboat. Just a boat.

It happened at Isle au Haut after a party ashore with friends. There was no wind. The sea was perfectly still. A gentle rain had settled over the harbor – the drops like chimes as they struck the flat seam of ocean.

This is what it’s all about, I thought. A time away from land and its cares – moments in which the sound of rain joining the sea is all there is. When we finally discarded our prejudices, the Back Cove – like all good boats – lulled us into a place circumscribed by islands and the healing rhythms of nature.