Sam Low

Just another WordPress site

New Book Charts Course to Hawaiian History Via Canoe

Olivia Hull

The Vineyard Gazette

Friday, July 12

Sam Low craves at least two things in life — the strong embrace of an ocean and the presence of a true ohana. He’s found both in two somewhat dissimilar places — Martha’s Vineyard and Hawaii.

Ohana is a Hawaiian word that means extended family. Mr. Low’s father grew up in Hawaii but moved to New England at the age of 17. On the East Coast, he sought a lifestyle similar to his Hawaiian upbringing and found it on Martha’s Vineyard, where “everybody let their hair down and everybody was fishing and clamming,” Mr. Low explained.

Growing up in Connecticut, Sam was exposed to Hawaiian cuisine, dance and hula — a form of prayer through dance. But Sam did not visit Hawaii until 1964 as a naval officer. His father died before he had a chance to reconnect with Hawaii, so Sam made it a lifelong mission to visit his father’s homeland. “I got a feeling I was going back for him,” he said.

Sam Low, now 70, served in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific from 1964 to 1966. In 1975 he earned a doctorate in anthropology at Harvard. As part of his studies, Mr. Low became fascinated by the subject of how the Polynesian people settled the many islands of the Pacific.

In his youth the popular book and documentary film chronicling Thor Heyerdahl’s famous balsa raft expedition from Peru to French Polynesia received a lot of attention, and many accepted it as truth. Mr. Heyerdahl’s theory, proven to his satisfaction by the 101-day voyage aboard the Kon-Tiki, was that the Polynesians were descendants of ancient South Americans who built rafts and voyaged across the Pacific from east to west to populate the islands.

In the early 1980s, Mr. Low produced a movie entitled The Navigators — Pathfinders of the Pacific, which countered the Kon-Tiki theory, saying that the descendants had in fact traveled from west to east setting out from Micronesia. To do this the boats would have had to travel against the winds and currents, something a mere raft could not do.

Mr. Low’s first book, Hawaiki Rising, which was published this past May, continues this conversation putting at the center of the story a double-hulled canoe named Hokule’a, a replica of the boats Mr. Low and others feel were key to the Polynesian diaspora. The H o k u le’a was a much more sophisticated sailing vessel than Mr. Heyerdahl’s raft and able to chart its own course to and among the islands of the Pacific. Mr. Low made many such trips as a crew member on the Hokule’a.

“The story is about the renaissance of Hawaiian culture, and the rediscovery of how our ancestors were able to navigate,” Mr. Low said. “They had to sail against the prevailing winds and currents, so they must have had very advanced equipment.”

On the voyages he attended in 1995, 1999, 2000 and 2007, he served as the official documentarian of the Hokule’a journey, composing 300-word posts each day.

Mr. Low’s cousin, Nainoa Thompson, became the book’s focal point. Having grown up in Hawaii somewhat disconnected from his tribal roots, Mr. Thompson became interested in learning the ancient craft of navigation using stars. For years, Hawaiians were treated as second-class citizens in Hawaii, and the language, culture and history of the native people were not taught in schools. Mr. Thompson became a protege of Mau Piailug, a skilled navigator.

Mr. Thompson’s story is made central “because it’s his coming of age in Hawaii at a time when Hawaiian culture was almost disregarded and lost,” Mr. Low said. Nowadays, Mr. Thompson is known as a respected 60-year old navigator, but few are aware of the risks he took as a youth to take on the legacy of ancient Pacific navigation, revitalize it and prove its efficacy to the world, Mr. Low said. In 2017, Mr. Thompson plans to stop in Vineyard Haven while sailing the Hokule’a around the world.

Through the process of discovering their former preeminence in oceanic navigation, some Hawaiians became possessive of the canoe and wished to exclude others from the process of rediscovery. Previous books and films made about the subject of the Hokule’a emphasized the friction between the ethnic Hawaiians and the haole — white members of the crew. Mr. Low preferred to focus on the anthropological and archeological side of story, as well as the biographies of each of the crew members. Mr. Low sought to employ as much of the Hawaiian language in his book as possible without confusing the reader. He also provides a glossary at the back.

“When Hawaiians discovered this story about themselves, that in fact they once were the world’s greatest sailors and navigators, and they discovered the oppression of their culture . . . they got very angry,” he explained. “I appreciated that side of the story but I realized that something was missing.”

As Mr. Low sees it, the canoe’s mission did not end with discord, rather it culminated in a renewal of pride and dignity for all of the Hawaiians involved, no matter their ethnic makeup. That’s the takeaway message of his own narrative.

“Hawaii today is one of the most rainbow of societies that there is. There are so many different races, so many different cultures,” he said. “The ethic of this canoe is that you are Hawaiian if you have that spirit in you, whatever race you are . . . come voyage with us, become part of this.” In fact, the story appeals to anyone who has experienced a process of discovering a lost cultural identity, he said. When he tells people he sailed on a Polynesian replica boat, people assume that it’s the Kon-Tiki he’s referring to. But he’s quick to correct them. Though in his book he doesn’t focus on what he calls “the battle of the theoretical,” his book can serve as an antidote to that misinformation. He and others believe instead that it was the ingenuity of their navigation and their engineering that enabled the ancient Polynesians to populate the Pacific, not the unsophisticated audacity Mr. Heyerdahl sought to recreate.

In his book, Mr. Low reconstructs the early maiden voyages, beginning in the 1970s, of the canoe to Tahiti and other islands of the region, piecing together snippets from more than a thousand hours of interviews with more than 100 affiliates. Mr. Low did not join the crew until more than a decade later, so he absents his own persona from the writing. “I want it to be a chorus of voices,” each speaking directly to the reader, he said.

Beholding the canoe was for Hawaiians a powerful moment. “The canoe carried a song from a time before remembering, a time so far in the past that it had been forgotten, or worse, a time that had been erased from memory so as to not reawaken an ancient hurt . . . but H o k u le’a overwhelmed such resistance . . . ,” Mr. Low writes in his book. Though his research took place in the Pacific, Mr. Low wrote a good portion of it and designed it on the Vineyard with the help of Nan Bacon and Tara Kenny. He published it in May, using Island Heritage Publications, a Hawaii-based printer. All told, he dedicated 10 years of his life to the book.

For the past three years, Mr. Low has lived on the Vineyard year round. “This Island is an ohana,” he said. If you just stay around, stand up and present yourself as part of the community, you will be accepted here, he said. This culture of this Island, like Hawaii, is informal and community-oriented, he added, and both communities were integral to the publication of the book. The final copies of the first edition are available for purchase at Island bookstores. Another printing is under way.

“People come here to relax and to be themselves,” Mr. Low said. “When the Island calms down, most Islanders pretty much love to get together with each other.”

- See more at: http://mvgazette.com/news/2013/07/10/new-book-charts-course-hawaiian-history-canoe#sthash.qf9ix6CM.dpuf

Hawaii Tribune Herald

Author Sam Low to present new book about Hokule’a

Sam Low will present his new book — “Hawaiki Rising — Nainoa Thompson, Hokule‘a and the Hawaiian Renaissance” — at two signings in Hilo. The free programs will be from 10 a.m. to noon on Tuesday, June 4, at Walmart and from 2 to 4 p.m. Saturday, June 8, at Basically Books.

Low also will present a slide talk at the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Kilauea Visitor Center at an After Dark in the Park event at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, June 4, and another with navigator Thompson at 7 p.m. on Friday, June 7, at ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center.

Low’s book tells the story of Hokule‘a in the words of the men and women who created and traveled aboard the 20th-century replica of an ancient Hawaiian sailing canoe, guided not by modern navigational techniques and equipment, but by ancient knowledge of the stars.

Chris Vandercook – The Conversation – Hawaii Public Radio – May 14th, 2013

Following the light, watching the motion of the waves and the flight of seabirds, ancient Polynesian navigator found their way to Hawaii and traveled the ocean at will using ways of navigating that later were all but forgotten. The revival of that ancient craft became one of the great stories of modern Hawaii when a generation rediscovered their heritage through the voyages of Hokule’a. That story has now been given comprehensive treatment by a man who witnessed it at first hand. Sam Low is the author of Hawaiki Rising and he is with us this morning.

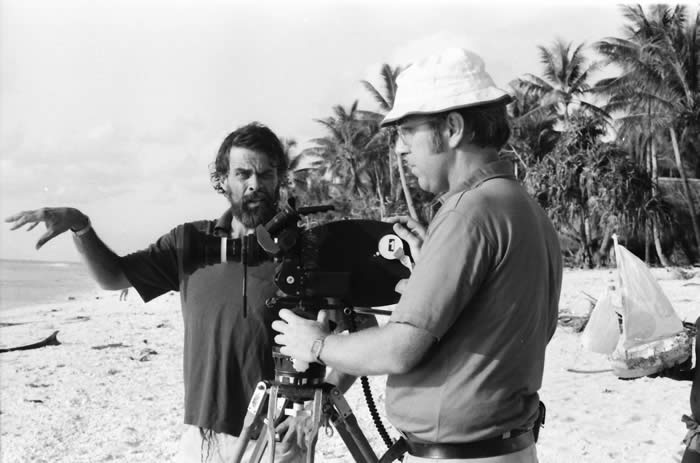

Sam Low and Boyd Estus

filming on satawal

1981

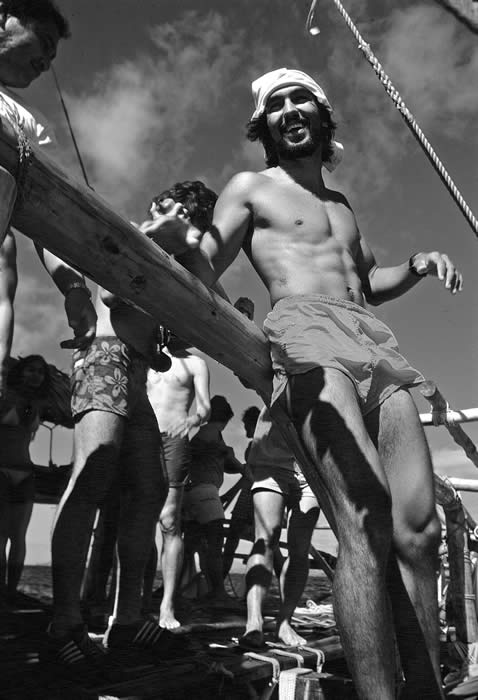

Nainoa Thompson – Hokule’a’s navigator

Nainoa Thompson as a young man

in 1980

Nainoa Thompson – Hokule’a’s navigator

“The vision of Hokule’a was conceived in 1973, so the publishing of this book marks the 40th anniversary of her creation. Sam Low, the author, has sailed with us on three voyages, written numerous articles and now, after ten years of work, has finished Hawaiki Rising. This book is an important part of our ‘olelo, our history, and it contains the mana of all those who helped create and sail Hokule’a.”

Honolulu Star-Advertiser Sunday, June 16, 2013

‘Hawaiki’ chronicles hopes tied to Hokule’a

By Gary Kubota

Sam Low’s “Hawaiki Rising: Hokule‘a, Nainoa Thompson, and the Hawaiian Renaissance,” captures in convincing style the heartbreak, sacrifice and hopes of the crews aboard the historic double-hulled sailing canoe Hokule‘a.

The book takes readers well beyond the first Hawaii-Tahiti voyage in 1976 that supported the assertion that Pacific islanders could navigate the open ocean without instruments, relying on signs in nature and the heavens, well before European expeditions to the Americas.

Low, who sailed on three subsequent Hokule‘a voyages in the Pacific, writes about the evolution and rise of the vessel as a symbol of the Pacific renaissance. The canoe’s founders and crew members provide new insight into the intense study and training of navigator Nainoa Thompson, as do the book’s black-and-white photos, star charts, maps and detailed illustrations.

“Hawaiki Rising” also brings into focus the selfless life of the late master navigator Mau Piailug of Satawal in Micronesia, who shared his knowledge with Thompson in hopes of reviving his own people’s wayfaring traditions.

The charm of this story is the realization that a community of supporters of varied ethnicities helped Thompson to achieve the goal of becoming the first Native Hawaiian noninstrument navigator in modern history.

It is a tribute to people with different goals and backgrounds who helped form the voyaging movement. They include Hokule‘a co-founder Ben Finney, who wanted to show that Native Hawaiians could have been capable of noninstrument navigation between Hawaii and Tahiti, and late co-founder and artist Herb Kane, who hoped for a rebirth in Hawaiian culture.

It is a tribute to learned people such as the late Bishop Museum Planetarium lecturer Will Kyselka, who gave Thompson access to the facilities at night to study and commit to memory the paths of more than 100 stars.

Most of all, it is a tribute to Piailug, who died in 2010, and the world of native wayfinders in the Pacific.

How can you tell if a flying sea bird is headed toward land?

If you see a moon with a halo, what kind of weather should you expect?

Low’s book gives readers glimpses of the knowledge of the natural world required by wayfinders like Piailug who knew the answers to these questions.

Readers also are left with a new appreciation for Thompson’s arduous path as he sought to renew native voyaging.

Author Gary T. Kubota was a crew member aboard the Hokule‘a during its 2007 sailing through Micronesia, receiving an “Editorial Excellence” award from the Hawaii Publishers Association for his coverage of the voyage.

“Hawaiki Rising: Hokule‘a, Nainoa Thompson, and the Hawaiian Renaissance,”

by Sam Low (Island Heritage, $24.95)

“View From Here” blog

By Kim Steutermann Rogers

Nov 22, 2013

Earlier this summer, I picked up a newly-published book and couldn’t finish it. Not because it wasn’t a good story but precisely because it was a good story–and I kept giving away my copy. After purchasing three copies, I finally managed to keep one long enough to finish reading the entire book.

That book was Hawaiki Rising by Sam Low, and as I do with most Hawaii authors whose books I read—and like—I reached to Sam to talk about his book and, hopefully, learn a few trade secrets in the process.

In 1976, a group of sailors boarded a double-hulled voyaging canoe with the intent of sailing from Hawaii to Tahiti. They provisioned themselves with food and drink but did not pack modern navigation devices of any kind. No GPS. No compass. Not even a sextant. Instead they would use stars, sun, waves and wind as their road map.

Hawaiki Rising is the story of the early years of the Hokulea, a double-hulled voyaging canoe built in the manner of the ancient Polynesia canoes that once traveled the big Pacific Ocean in search of land. In sailing to Tahiti in 1976, Hokulea not only pulled some islands out of the sea and proved the original discovery of these Hawaiian Islands was no accident but pure scientific discovery. In the process, Hokulea restored a culture from near extinction.

“There is also a deep universal philosophy of life here, I think,” Sam Low told me. “It is a story behind the story of adventure and culture—it is universal. I hope.”

Sam Low and I traded a series of emails over a couple weeks. Here’s how our conversation went:

I can see that writing Hawaiki Rising was no small endeavor. I mean, the research alone must have taken years. Do you have any idea how many hours you spent researching—interviewing, reviewing logs, diaries, historical record and such?

I spent so much time researching and writing the book it is hard to calculate. I made three voyages on the canoe and one on an escort boat, taking notes and photographs all the time. I wrote more than a dozen articles for national magazines which was part of the preparation for writing the book. I would say that I must have spent at least three years, full time, over ten years writing Hawaiki. That would be about 6,240 hours just on the book—at least. And don’t forget that I spent two years before that making my movie–The Navigators–which contributed to my knowledge of the subject. It was a labor of love—or a kuleana, as we say in Hawaii—a privilege and a responsibility.

I know you grew up on the East Coast and now live on Martha’s Vineyard. Will you share your story of connection with Hawaii?

My father was sent away [from Hawaii] to school in Connecticut when he was 17 years old. The story goes that his father went bankrupt at home and he had no money to pay for his son’s return – so my father decided to make his way in New England. He grew up to become an artist, teacher and director of an art museum in New Britain, Connecticut, married a beautiful and talented New Englander, had me, and stayed on.

I knew that my father was different from other dads at an early age. For one thing, he did not work in an office, he went to his studio to paint, or to Loomis School to teach art, or to the New Britain Museum of American Art where he was the director. My mother was an artist, too, so I grew up in a very creative family. And my father was the only dad that I knew who played the guitar and sang songs in Hawaiian. The fact that I was part Hawaiian didn’t really have much meaning for me, growing up in a very haole world in New England. What fascinated me most were stories my father told about HIS father – a famous cowboy from the Big Island known as “Rawhide Ben Low.” How could I not be interested in a grandfather who was a cowboy? I loved dad’s stories of Rawhide Ben growing up on the Parker Ranch, hunting wild cattle on the slopes of Mauna Kea, losing his arm in a roping accident, and founding Puuwaawaa Ranch. Still, I really did not know what “being Hawaiian” meant.

In 1964 I was commissioned as a Naval Officer and ordered to a ship in Pearl Harbor – which was my choice – I wanted to see Hawaii.

My plan was to drive a battered Volkswagen across country to San Francisco, ship the car to Hawaii and fly to join my ship. On the day that I left home, my father took me aside.

“I will see you in Hawaii,” he told me. “I have not returned but now is the time. You will be there and I want to see my family.”

He died in his sleep that night of a massive heart attack.

Later, in Hawaii, an elderly cousin took me aside. “When your father never came back, some of us in the family were angry with him. We felt that we were not good enough for him. But there is another reason. When he left the islands, he went to a kahuna for a blessing. The kahuna told him that he would die young and that he would never come home. I think he did not come back because he was afraid to. And now the kahuna’s story has come true. But I am glad that you are here. In you, he has come home.”

It was not until I arrived in Hawaii for the first time in the fall of 1964, as a young naval officer stationed on a ship home ported in Pearl Harbor that I began to get an inkling of my Hawaiian identity.

I lived on Sunset Beach for about six months in a house I rented from Fred Van Dyke. During that time, I got to know my aunt, Clorinda Lucas – and I was introduced to an old-time, authentic Hawaiian life style by staying with her in Niu Valley. Clorinda was a well-known social worker who dedicated her life to helping Hawaiians. Almost every day, Hawaiian families would visit her home in Niu and be welcomed to discuss their lives, their joys and sorrows, with Clorinda. And, when needed, Clorinda would find a way to help them. It was this “helping” ethic that I found most fascinating and that introduced me to, if you will, the “aloha spirit.”

At that time, I did not really see much left of an authentic Hawaiian culture. None of my family spoke Hawaiian – with the exception of Clorinda who knew a few sentences and phrases. All of them, like so many Hawaiians, had been raised to deal with a haole world. I did not see any classic hula. The culture seemed to be dying.

In 1976, I read about H?k?le‘a and her successful voyage from Hawai‘i to Tahiti – carrying her crew 2400 miles in thirty-five days. Even more astonishing, she was navigated by Mau Piailug, a man from a tiny Micronesian Island who found his way as his ancestors always had, without charts or instruments, relying instead on a world of natural signs. I determined to make a film about this story and to tell it from the perspective of the scientists who had discovered the truth about ancient Polynesian explorers and men like Mau Piailug who continued to sail in the old way.

I spent two years traveling the Pacific with experienced archaeologists as guides, retracing steps taken by early Polynesian mariners. I sailed with Mau Piailug from his home island of Satawal. He told me how he navigated by the stars and by signs in the wind and waves using secret knowledge handed down from father to son over thousands of years. I spent time in Hawai‘i with Nainoa Thompson who combined Mau’s teachings with his own discoveries to reveal how ancient Polynesians may have guided their canoes. I began to feel a stirring in my blood. I am one-quarter Hawaiian, and three-quarters haole—descended from a Hawaiian ali?i (a chief) and a New Englander who ventured to the islands in 1850 seeking wealth and bringing with him disease and an alien way of life. At first glance, this influx of outsiders seemed to have destroyed Hawaiian culture. But as I visited the islands more often, I discovered an astonishing revival of the Hawaiian language, poetry, dance and all the other arts of indigenous life. Hawaiian culture had not died. It had gone underground—waiting for a spark to ignite it. That spark was H?k?le‘a.

What’s also quite evident in the story is the access you had to the key players of Hokulea and the Polynesian Voyaging Society from the early days. How did that come about and what was that experience like? Were people forthcoming? Shy? Resistant?

Nainoa Thompson is my cousin, so when I visit Hawaii – usually every year – I stay with my family and Nainoa lives about 100 feet from my guest house residence. I was able to talk with him on hundreds of occasions. We developed a deep mutual trust and affection which allowed me to ask intimate questions and allowed him to respond.

In addition – voyaging aboard Hokule’a allowed me to connect to crewmembers on a deep level. Before writing the book I posted hundreds of stories on the web, wrote magazine articles and the like which developed trust that I would fairly represent everyone I spoke with. And – it is also an obligation on the part of crew to get their story out to the public and they recognized that was my task – to help them do that – as documenter.

Why did you decide to just write about the early years of Hokulea and the Polynesian Voyaging Society?

The early years were the most important and the most dramatic in my opinion. Hokule’a has had such a stunning history – 40 years since inception and 140,000 miles of voyaging – that I needed a shorter time span. There was too much to cover. The first years were the time during which the ethos of voyaging evolved, the universal view of the importance of the quest to find ourselves as human beings–not only as Hawaiians. That is the central story–what makes the quest so universal – and all that happened in the first seven years of Hokule’a’s evolution and that of the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

The narrative reads like a nail-biter. There’s tension and drama throughout–and I even knew the ending. Did you consciously think about this as you were writing and what inside writing techniques can you share that helped you achieve such an interesting read?

I am a student of a kind of writing style called literary non-fiction in which the author uses all the elements of fiction storytelling—character development, plot, setting, theme—to tell a non-fiction story. It was always my goal to write a “good read” while being accurate to the facts. I read and reread authors like Joseph Mitchell, John McPhee, Tracy Kidder to learn the style.

Was it difficult to find a publisher? What was that experience like?

It was not difficult to find a publisher. I was interviewed by five of them in Hawaii, including the University of Hawaii Press, and they all wanted to publish the book. But, in the end, I decided to publish it myself because I wanted to keep control of the book—to choose and design the cover, the text layout, and be in charge of every detail that went into the book. It was a sacred obligation to the Ohana Wa’a to do that, and I did not want anyone else having control over the process.

The response to the book from what I’ve seen is nothing but favorable. Overall, it’s getting four stars on Amazon.com, and the first print run must have sold out quickly, because I had a hard time finding it in Hawaii. What kind of feedback are you hearing from people when you do readings and/or public events?

Actually, they are five star reviews – out of a possible five – and I have received 35 of them so far from readers. The book sold out in five months, 3,000 copies, and is now in its second printing.

The personal response has been very, very gratifying. I released the book at the Hawaii Book and Music Festival, and Nainoa and I signed over 100 books with people waiting in line for an hour.

I released the book in Hawaii first because it was important that Hawaiians approve of the book before I sold it on the mainland. The response was so enthusiastic that I believed that I had the approval of my crewmates and fellow Hawaiians, so I released it on the mainland a few months ago.

http://www.outrigger.com/explore/hawaiian-islands/view-from-here-blog/2013/Nov/talk-story-with-author-sam-low