|

Hawaiian

Genesis

Travel Feature - Boston Sunday Globe

By Sam Low

|

Jealous, moody, easily enraged, the

goddess Pele is the primal force that has thrust the Hawaiian islands

from the sea. She has fashioned the blasted moonscape on either side of

us as we take Chain of Craters Road through Hawaii's Volcanoes National

Park. A gentle fog slicks a recent lava flow, creating a shimmering stone

pudding that vibrates with her power. Here and there, a few spindly trees

force their roots deep into tiny crevices in the lava. Older flows are

covered with moss.

My cousin Kim Hart and I have come to Hawaii to discover and photograph

the forces - natural and human - that have created the "big island." Kim

is an American photographer based in Norway. I am a television producer

and writer. Although I live in Boston, I am part Hawaiian - my father

and grandfather were born in the islands. This trip is a return to my

roots.

Descending toward the coast, Chain of Craters road bends in a tight switchback.

The ocean swings wide before us, a shimmering blanket to the vanishing

point. In spontaneous awe, we exclaim aloud. We stop. The road snakes

down the Holei Pali fault scarp and disappears suddenly behind two pillars

of smoke rising majestically where active lava flows meet the ocean.

At a National Park Service roadblock we pull over and unload our cameras.

A Ranger warns us of the dangers ahead:

"Don't wander into the active flows!" he tells us. "There are lava tubes

that will give way beneath your weight. Your next stop will be a bath

in molten lava. And be careful near the edge of the lava beds. The cliff

fractured and a tourist plunged a hundred feet into the ocean. We never

found him."

We have arrived at the Golden Hour, the time just before sunset when the

coast is painted in a gentle yellow sheen. Ribbons of lava are revealed

in the gathering darkness. A scarlet stream flows down a volcanic delta

and cascades into the surging ocean. Clouds of steam obscure its glow.

We are surrounded by hundreds of tourists but they are stunned to silence

by the awesome natural spectacle. I hear a muffled popping like a package

of Chinese firecrackers exploding in the distance - the sound of molten

lava as it is extinguished by the ocean's embrace. Kanaloa, god of the

sea, and Pele, goddess of fire, are mating in an ancient ritual of island

building and wearing away.

Geologists know that Pele is the primal engine of our planet. Dozens of

miles beneath where we sit watching her fireworks, is a "hot spot" - a

point of intense thermal energy. As the abyssal ocean floor rides the

Pacific plate to the northwest, a few inches a decade, it passes over

the hot spot. Molten magma flows upwards to form the Hawaiian island chain.

Kauai formed five million years ago. The plate carried it northwest. Oahu

slid over the hot spot and coalesced, then Molokai, Lanai, Maui, and Kahoolawe.

Hawaii is still forming right in front of us. Because Kauai is older,

it's landscape is deeply eroded by tropical rains. Hawaii, the youngest,

retains its voluptuous curves.

The next day, we ride the curve of Mauna Loa on Highway 11, descending

the ancient volcano's gentle arc toward the district of Puna. We follow

route 130 until it dead ends where glistening mounds of lava have pushed

into the sea to form a new coastline. Beneath are dozens of cement foundations,

all that remains of tract houses built in harm's way only a few decades

ago.

Puna is home to a human tide that washed over the islands in the late

sixties. Pahoa, once a sugar plantation town, now bustles with New Agers.

Former Japanese storefronts are emblazoned with signs that advertise natural

foods, Zen therapists and paraphernalia for the enjoyment of marijuana.

A few aging hippies with long flowing beards stare at us as we drive past.

Kim and I move on, seeking the remnants of an older Hawaii.

We follow a narrow road, bordered by thick stone walls. I imagine they

were built by the retainers of ancient Hawaiian Kings or the hired labor

of long gone plantation barons. On each side, the land rises to the height

of a tall man, like the roads in Wales that run below high hedge rows.

Perhaps, as in Wales, this road has been dug into the earth by centuries

of traffic. Suddenly, we enter a natural cathedral of trees towering a

hundred feet to a canopy of delicate green lace. Looking up, we see a

river of light where the leaves have touched each other and have been

worn away as they sway in the constant Trade Winds. We are dwarfed by

an explosion of leaves - spear shaped, rounded, lacy. I imagine the dense

growth conceals the ruins of a magnificent planter's house, its gardens

lost in creepers, its verandah fallen in upon itself. There is the aroma

of moist growing things, a lingering smell like that of rotting coffee

grounds.

That night, we drive up the northern flank of Mauna Loa toward the town

of Waimea. The sun sets ahead. A low pressure area has passed over the

island, bringing steady northern winds, cleaning the air. Against the

sun's glow, windbreaks of Ohia trees fan bare limbs against the sky. Cattle

stand on small rounded hills in crisp silhouettes. Darkness sets in quickly.

Waimea sits in the saddle between Mauna Kea to the south and the Kohala

Mountains to the north. This is the home of the world famous Parker Ranch,

the largest family-held cattle outfit in the world. The ranch was founded

by my great-great grandfather, John Palmer Parker, a native of Newton,

Massachusetts. In 1815, he was among the first white men to settle in

Hawaii.

Twenty-three years before Parker's arrival, King Kamehameha the first

received a gift of a bull and five cows from the British explorer Vancouver.

The king ordered that no-one touch them, under penalty of death, so they

would multiply. When Parker arrived, the mountains around Waimea teemed

with wild cattle, poising a threat to man and nature alike. Parker received

the sole privilege of hunting these cattle for hides and meat. After marrying

a royal chiefess, Kipikane, Parker built his home on the slopes of Mauna

Kea at the end of a horse trail, a few miles from Waimea.

"It was an enchanting place, luxuriant with Hawaiian forest growth," wrote

my great Aunt, Mary Low, who grew up on the Parker homestead. "They loved

the Mamane, the Maile, the Hapu'u tree ferns, the many birds of yellow,

green, and red and the black ones with yellow tuft-feathers, singing and

flying about. Kipikane wanted to live there immediately... 'At once! At

once' as she said happily. In a couple of days there were two new hale

pili (grass houses) being erected by her numerous retainers."

The hale pili were soon replaced by a proper New England salt box home

which Parker finished off with a gleaming interior sheath of Hawaiian

Koa, a wood like Mahogany. The original house still stands where it was

built, but a more accessible replica is at Pu'u'opelo, in Waimea, which

is open to visitors. Kim and I visited Pu'u'opelo and the nearby Parker

Ranch Museum in Waimea Town to piece together the history of this famous

family.

Parker became a renowned hunter of wild cattle. Roaming the Kohala mountains

and ascending the slopes of Mauna Kea with his percussion cap musket,

he built his first fortune by selling the meat to visiting whale ships

and the hides to markets as far away as Boston. Later, he purchased land

for a ranch and imported Mexican vaqueros to teach Hawaiians to ride and

rope. Today, Hawaiian cowboys are called Paniolos which is a "Hawaiianization"

of the Spanish word for Spain - Espanol. After Parker's death in 1868,

his children continued to grow the ranch. Today it sprawls over 227,000

acres of the finest grazing land in Hawaii.

Surrounding Parker Ranch are many smaller ones with poetic Hawaiian names

- Huehue (overflowing again and again), Kahua (the foundation), and the

ranch my grandfather started in 1884, Puuwaawaa (peak with gulches). On

Thursday, we take the high road over the Kohala Mountains through ranch

lands shrouded in mist called Vaug. It's caused when the clouds of volcanic

steam from Mauna Loa float into these mountains - the same clouds we had

seen a few days earlier rising over Chain of Craters Road. Suddenly the

sun breaks through. The pastures glow with a green so brilliant that it

seems the light must be coming from deep beneath the earth.

Ahead, we see cars and pickup trucks parked by the roadside. We stop.

Cowboys are branding cattle. We join a crowd gathered around a large fenced

paddock to watch flames leaping off the calves' haunches as red-hot branding

irons are applied. The aroma of burning flesh drifts over us. Suddenly

a calf breaks free and races for the open grazing land. Two cowboys riding

lathered horses gallop in pursuit. A lariat is unfurled, arcs through

the air, and neatly encircles the calf's hind legs. The cow pony backs

on its haunches. A husky Hawaiian wrestles the calf to the ground and

a team swarms over it. My grandfather, "Rawhide Ben" Low, described just

such a scene in his memoirs - a scene that took place a century ago:

"I have seen as many as two hundred men take part in the big Parker Ranch

drives. There are many others who sit atop the corral walls to watch when

the branding begins. Only expert riders and ropers can control the calves

efficiently and tenderfeet would only be in the way or add danger to the

cowboys and themselves. Not only are the cowboys and horses carefully

selected, but also the crew handling the throwing of calves, tending the

fires and the branding irons. The branding men must be strong and fast

and know their business of burning just right. Several others must be

expert in castrating and ear marking for these jobs require skill and

precision."

During a rest break we meet the owners of the ranch, Angie and Pono Von

Holt. Angie tells us that their ranch, Pono Holo, is small by Hawaiian

standards, 10,000 acres with about 7,000 head of cattle. Even so, its

a big business. The Von Holts fatten the calves here during the wet Winter

months when the grass is tall and verdant. In the summer, they are shipped

to another Von Holt ranch in Oregon for final fattening, then to the slaughter

houses in Chicago.

Driving home that night we stop just above Waimea to watch the sun set.

In the distance, Parker Ranch grazing lands sweep gracefully up toward

the summit of Mauna Kea over smoothed low hills punctuated by cinder cones.

As the sun sinks lower, giant cumulus clouds heave their bellies over

the summit. Emerald green paddocks stretch from about half way up Mauna

Kea right down to the shimmering ocean 15 miles away. The only sound is

the gentle bellowing of cattle.

It is hard to imagine what this scene must have looked like only a century

ago when the slopes of Mauna Kea were covered by native forests. That

night I thumb through the faded pages of my grandfather's manuscript to

find his description, written in 1939:

"As I sit here and write these few lines, it brings back memories of that

magnificent growth of stately trees and dense growth of ferns, so thick

that it was a physical impossibility for man or beast to penetrate. The

whole forest was a living swamp, ponds of water everywhere, wild ducks

by the thousands. This dense forest extended from the 5,000 feet elevation

to 3 miles from the coast and hardly a stream that has an outlet to the

ocean was ever known to be dry. And just consider that this forest has

disappeared within my memory and not a log or a tree trunk of 4 or 5 feet

in diameter can be seen, all disappeared into eternity, ashes, and the

memory of the old timers, and I am one of the last. Since the introduction

of cattle, goats, sheep and hogs with no provision of safeguarding the

forest by fencing, that forest has disappeared in the astounding short

time of 60 years."

The next morning, Kim and I watch the sun rise from the verandah of our

rented house. Mauna Kea sweeps in a graceful arc from the sea to an altitude

of 13,600 feet. We decide to find out what the view is like from its peak.

The summit road curves through unfenced Parker Ranch range land where

we are on the lookout for wandering cattle. At about 8500 feet above sea

level, the road works through low hanging clouds. The ascent is steep.

The air thins. We feel light headed. At 11,000 feet, we break through

the clouds into clear blue sky. Ahead, the road to the summit of Mauna

Kea ascends so steeply I wonder if our car will make it.

At the road's end, about 13,000 feet above sea level, crisp geometric

shapes rise into the azure sky - observatories that search deep space

through the clear air at this high altitude. In the thin air and gathering

cold, I find that I must move slowly or I will be winded. The winds here

can reach a 100 miles an hour, but today they are light and pleasant.

By six P.M., the sun sinks quickly toward the cloud layer, painting the

observatories a gentle pink. The cold seeps in under our parkas. To the

north-west, Maui floats in a sea of cotton. As the sun drops, the horizon

becomes blood red and the sky deep purple. Giant slits in the observatories

open - the domes swivel to their assigned area of deep space. For the

astronomers it is time to go to work. For us, it's time to go home.

I have been warned not to ride the brakes during the steep descent, so

I pump them when we reach twenty miles an hour. Darkness envelopes us

and for a time we seem to be flying through a sea of diamonds. Never before

have we seen the Milky Way so clearly. In low gear, it takes 45 minutes

to make the 8 mile descent.

Not knowing the danger, we made the trip to the summit in a rented economy

car. Later, I read the following in a Guidebook: "Don't even think about

driving an ordinary passenger car all the way up Mauna Kea, even in the

best of weather. ...You can't gear an ordinary passenger car down far

enough to descend the steep road without riding the brakes. You'd almost

certainly burn out the brakes, lose control of the car, and join the ghosts

of others who've lost it on that road. It is possible to drive up and

back if you rent a suitable 4WD vehicle."

On Saturday we take the shore road along the Kawaihae Coast toward Mahukona

Harbor. The land on both sides seems arid, useless for human habitation.

But from the road we see stone platforms which mark the place of ancient

temples or heiau. I remember once flying over this landscape in a helicopter.

In the slanting early morning light I saw thin spidery lines, arrow straight,

stipple the land below - all that remains of stone walls built by ancient

Hawaiian farmers. Perhaps the early Hawaiians knew how to cultivate crops

in a dry environment, but more likely, before the ravages of cattle and

sugar plantations, this place was once much wetter.

We turn down a one lane road toward Mahukona - once a port where cane

sugar was shipped to the mainland from thriving plantations. Today, all

that remains are foundations and rusted bits of metal.

"The labor in South America was cheaper and the land more valuable for

development than for farming," says Sonny Solomon, our guide for the afternoon.

We have come to Mahukona to visit a much earlier site, the Ko'a Holo Moana

heiau, a temple dedicated to the arts of Polynesian navigation. The first

Polynesian seafarers set out from Tonga to explore the vast Pacific Ocean

about 1300 BC, as the walls of Troy were falling to the Greeks. By the

time of Christ, they had discovered and settled most of the great Polynesian

triangle with the exception of the most remote islands of all - Hawaii.

Some archaeologists think that the first Polynesian canoes arrived at

South Point, the southernmost tip of the Big Island, about 1000 AD The

Navigators who guided those canoes were revered in ancient Hawaiian society.

Sonny and I scramble up a steep hill to the heiau which sits on a promontory

above a small bay.

"The ancient Hawaiians had a canoe anchored right there," Sonny tells

us, pointing to the bay, "and the student navigators slept on the canoe

to feel the movement of the waves which they would use as a natural compass

when they became full fledged navigators."

Today we know a great deal about this wayfinding art because of the voyages

of Hokule'a, a replica of an ancient Hawaiian canoe, which first retraced

the route between Hawaii and Tahiti in 1976. Sailing across 2200 miles

of open ocean, the canoe was guided by one of the last navigators to know

the signs written in waves and stars, Mau Piailug from the tiny Micronesian

atoll of Satawal. In 1981, I journeyed to Satawal to produce a PBS documentary

about Mau's seafaring skills. I sailed with him aboard his swift proa

which he fashioned without plans from the log of a breadfruit tree. At

night, in his darkened canoe house, he unfolded a woven pandanus mat before

me and placed 32 lumps of coral upon it to represent the rising and setting

points of the stars that define his "star compass." He taught me the direction

of ocean swells that he steered by when clouds obscured the sky. Mau allowed

me to enter a world in which writing, maps, sextants and compasses were

replaced by a knowledge of nature so profound that he could sail with

confidence anywhere in the world. Since then, Mau has taught young Hawaiians

to navigate in the traditional way and his students have sailed 45,000

miles aboard Hokule'a throughout the Pacific to kindle a new pride among

all Polynesians.

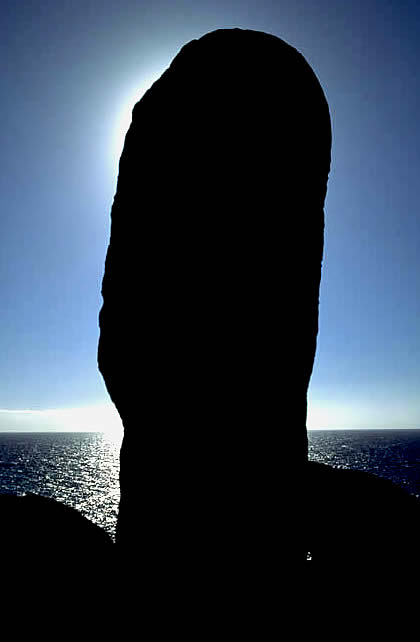

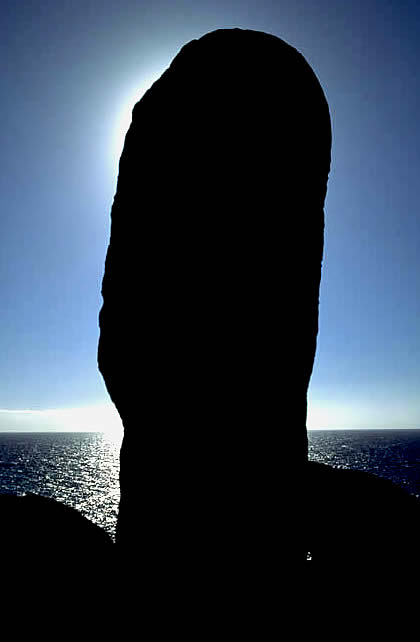

Ascending the hill at Mahukona, Sonny stops before a tall standing stone.

"That is Kanaloa," he says, "it's got to be because it's the nearest to

the sea."

Up-slope from Kanaloa is a platform of black volcanic rock dominated by

dozens of stone pillars radiating away in myriad directions. There are

many strong alignments - three pillars seem to march in the general direction

of Tahiti, others could be solstice markers. Sitting on the heiau, I imagine

a double hulled canoe at anchor in the bay. In the distance, another canoe

sets out with a class of navigator apprentices for a session at sea. For

these ancient mariners, the ocean was a road that joins Hawaii to Tahiti

and on to the Cook islands, to New Zealand, and to the thousand other

islands that make up the greater society of Polynesia.

On Sunday, our last day, we descend from Waimea along a road that drops

2500 feet to the tiny town of Puako on the South Kohala coast. Here, thirty

years ago, I remember driving a jeep down a one lane track to my family's

beach house at Paniao ( "place of swirling waters" ). In 1964, Paniao

was ten acres of lava, crab grass, and a shack blackened by decades of

salt spray where we lifted shutters to let the Trade Winds blow through

and lit kerosene lanterns at night. Today, the shack is gone. In its place,

a rock star and a local entrepreneur have built two majestic homes. Development

catapulted taxes so high that my family was forced to sell the land. Along

miles of coast, where fishing shacks once stood, Kim and I find palatial

homes. A small ocean front house lot costs a million dollars, or more.

Resorts spread golf courses over once barren lava beds. We drive on to

keep a scuba diving appointment at one of them.

Anchored off an eroded lava flow, we slip beneath the ocean's surface

to a world that has escaped the forces of development, the domain of Kanaloa.

If Pele is fierce and hot, Kanaloa is gentle and cool. We hang suspended

over a reef, moving with the regular swell. Beneath us, a sea turtle is

tended by rainbow hued fish with lyric Hawaiian names, Lau'i-pala, Kihikihi

and Paku'iku'i. All around us, Kanaloa has reshaped the work of Pele to

his own artistic tastes, smoothing sharp edges of lava flows and adorning

them with coral. We swim through lava tubes, natural arches which formed

as the molten rock cooled. Later, as we bask in the bright sunlight, I

admire Kanaloa's shimmering surface. It is the ancient road that beckoned

Polynesians to feats of exploration that no other people have quite equaled.

Compared to them, the Greeks, our heroes of the dark ships, were timid

coast-huggers. Fearful of sailing at night, they beached their ships when

the sun set. The Polynesians welcomed darkness for the stars provided

a compass by which they steered their powerful canoes. Fifteen hundred

years before Europeans learned to fashion sea-going vessels staunch enough

to discover Hawaii, the Polynesians had explored and settled the entire

Pacific, one third of the earth's surface. Kanaloa provided the highway

- a deep human urge to explore carried the ancient Hawaiians across it.

Tomorrow, Kim will fly back to Norway and I will return to writing a book

about my Hawaiian grandfather, Rawhide Ben, and his cowboy world. In only

five days, we have managed to sample the Hawaiian genesis - the forces

that shaped this island state - the deep pyrotechnics of the earth's core

that are expressed all around us; the first Hawaiian settlers who built

their settlements to blend with nature so well that traces of them have

virtually disappeared; my New England ancestors who realized profit from

cattle and sugar, forever changing the face of the island. And at the

very pinnacle of Mauna Kea we found men and women who imagine voyages

to distant stars and plot the maps that may someday guide astronauts to

new settlements.

As I thought of these modern explorers, I realized that they will pilot

their course by the same stars that once guided Polynesian mariners as

they crossed the vast and heaving road of Kanaloa - to Hawaii.

|