|

Loko'Ia

Kia Loko, Guardians of the Pond

By Sam Low

Hana

Hou Magazine

Kahili Award, 2001, Hawaii Visitors

Bureau award for best article celebrating Hawaiian culture.

Hawaii Publishers Association Pa'i award, 2001, Editorial

Feature, first place.

The shoreline is rocky and interspersed with pockets of clear sand beach

and stands of coconut palm bending in the northeast trade winds. There

is the constant sound of surf along the reef and a view of Maui and Lanai

against the southern horizon. But the most prominent view is of a large

stone wall pushing into the lapping waves and enfolding a circle of water

against the shore. This is Kahinapohaku fishpond on Molokai.

The western wall of the pond has been restored to a distance of about

200 yards five feet high and five feet wide with large fitted stones on

two sides and smaller stones between as fill. To the east, the restored

wall extends from thirty yards or so inland along the beach and out into

the sea for perhaps another 100 yards where it becomes a slender line

of disordered stone circling around to join the western wall. Only a year

ago all that was visible here was a slim pile of rocks. The restored part

is a testament to the work of a team of men and women who have braved

a daunting bureaucratic gauntlet to begin a three year project that will

return the fishpond to its former grandeur and productivity.

Rebuilding Ancient fish pond

The team is called Loko I'a Kia Loko - guardians of the fishpond - and

Scott Kauhanehonokawailani Adams is their supervisor. He is a handsome

Hawaiian with broad shoulders and a bright smile. In his eyes are bursts

of good humor leavened with pain. Scott freely admits his checkered past

- brushes with the law, six years of heavy drug use - the result of a

deep depression and sadness that he felt whenever he considered the fate

of his people.

"I go to Waimanalo and I see my brothers and sisters living in 1500 square

feet," Scott says, "cannot raise nothing. Penned up in tiny lots. How

they going to live like Hawaiians? I watch TV and I see Hawaiians being

kicked out from Sand Island. I think, 'what happened to our people?' In

school they teach me about Napoleon Bonaparte and I wonder why am I learning

about this man - what does he mean to me? Where is the history of my own

people? And when they teach us about Kamehameha all I learn is he is one

war-like fierce man. I feel like I am a round peg trying to fit into a

square hole. To be successful I've got to have a garage, a car, a dog,

a cat and 2.2 children. I could not see how I was going to achieve that

so I no like being Hawaiian."

Then came the anger. In the rising tide of Hawaiian awareness, of activism

on Kaho'olawe and the ensuing renaissance of Hawaiian pride, Scott returned

to his homestead on Molokai. He erected a tent and hauled water in 55-gallon

drums. He farmed. He spent time alone, thinking about his life.

"The anger was part of the learning process," he says now. "I learned

about the overthrow and the wrongs done to our people. Those were the

militant years. I thought I might take action like at Wounded Knee. I

cried in my tent. I thought, 'for what purpose am I smoking crack? Why

am I making trouble?' And then I remembered something that my father said

to me - 'if you are not part of the solution, you are part of the problem.'

Those angry years were a process of learning. They were enlightening years.

I learned that I was Hawaiian and that I had to find a solution to our

problems as a people."

There were many mentors during this period of enlightenment in Scott 's

life. There were men like George Helm, Emmett Aluli and Eddie Aikau. And

there was Walter Ritte.

"I truly love Walter," Scott says, "because he went through the ringer

for Hawaiians. He always thinks of his people first."

And there were his own kupuna who taught him, as Scott puts it, "to preserve

what generations of my ancestors made and to add my two cents to it" -

advice that he would soon find a way to incorporate into his life. There

was also Hokule'a: "when Hokule'a set sail," Scott explains, "I realized

that my people were extremely smart. The Europeans sailed from one big

continent to another. Columbus could not miss finding land; it was right

there in front of him to crash into. But the Hawaiians sailed from one

tiny speck in the Pacific to another. And they did it long before Columbus.

That was something to be really proud of."

"Then Hokule'a started voyaging all over Polynesia," Scott continues,

"and canoes started popping up everywhere. Makali'i and Hawai'iloa in

Hawaii, others in Aotrearoa and the Cook Islands. I got glimpses of Hokule'a

on TV and what impressed me was how simple the canoe was. I used to think

that only high tech things were beautiful, like a Lamborgini, for example.

But now I saw flashes of a different kind of beauty in Hokule'a and I

saw pride in our people whenever the canoe came in. It was a renaissance.

It was snowballing."

Looking around for something to do, Scott remembered the words of his

kupunas - to preserve and add his 'two cents' to what his ancestors had

left behind. The answer was all over the Molokai landscape - fishponds,

seventy-three of them, all crumbling into the ocean from disuse.

"I saw the fishponds were scattered just like we as a people were," Scott

says. "They and we were not together as one, there was no unity. I saw

that if I did one simple thing - put the rocks back together again - it

would be symbolic of all the Hawaiians coming back together again."

It was a long process. Scott found that you could not just go out and

rebuild an ancient fishpond. There were literally dozens of permits to

obtain - local, state and federal. And the physical work itself was daunting.

A tidal wave had swept ashore in the late 1800's taking out part of the

wall when it came ashore and another part when it receded. All was in

ruins. Akamai now to getting things done in western ways, Scott and others

pursued funding from an alphabet soup of organizations - the EPA, OCS,

CETA, DCSC and EC among them - convincing many that fishponds could provide

a model of how ancient resource management techniques could apply today.

"I think of the fish ponds being like the canary that miners took deep

into the shafts with them," Scott explains. "If the canary died it indicated

that there was poison gas in the mines and the men got out of there fast.

Same thing with the fishponds. If they are unhealthy it means that whole

ahupua'a is unhealthy all the way to the mountaintop, and if the land

is unhealthy then the people cannot be healthy. So if we begin to make

the fish pond healthy once again we help make the land and our people

healthy too."

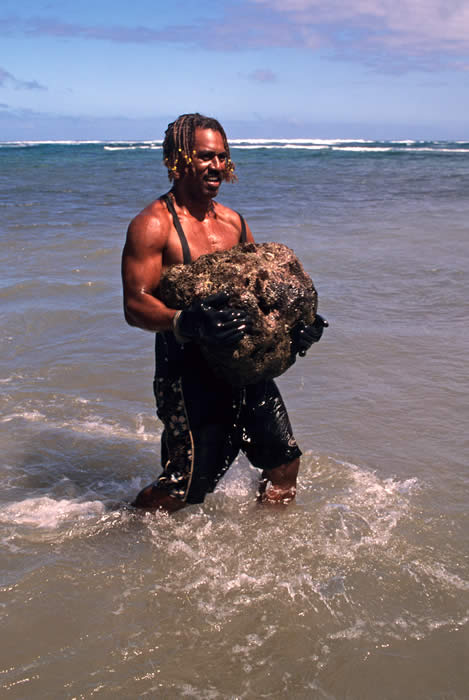

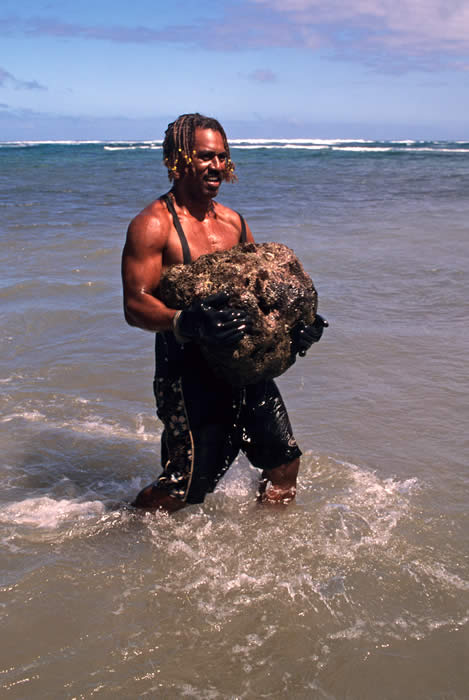

Volunteer carries rock to rebuild wall of fish pond

I found one sure sign of health at Kahinapohaku fishpond on Friday, March

3rd, when I visited to interview Scott about his work. More than thirty

young men and women were there with their teachers from Waipahu high school,

rebuilding the walls of the pond. I had met them earlier, courtesy of

their Molokai guide, Kekama Helm - a crewmember aboard Hokule'a on the

first leg of the voyage to Rapa Nui - from Hawaii to the Marquesas. When

Kekama is not voyaging, he works for the Queen Lilioukalani Children's

Center on Molokai - the kid's local host organization. On the beach, a

dozen or so young women filled bright blue plastic buckets with small

stones while in the gentle waves offshore young men filled their buckets

with larger stones and wrestled up boulders to carry to the wall as fill.

They often sang Hawaiian songs as they worked. Laughter and shouts of

triumph punctuated the sound of offshore surf as each bucket was emptied

into the space between the tall retaining walls. Scott beamed at the men

and women bending over this arduous task.

"When we get akamai kids like these here to work on the pond," he says,

"I think I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. When I was their

age in my heart I was not Hawaiian. I looked like a Hawaiian. I smelled

like a Hawaiian. But in my heart I was not Hawaiian. What I did was not

Hawaiian. Now when I look out at the kids I come happy. Here are Kanaka

Maoli doing their duty, fulfilling their obligations, working hard."

And in their own hearts, the young men and women of Waipahu High School

were indeed Kanaka Maoli. I had seen it the day before when they visited

the ancient lo'i in the Halawa Valley that Glen Davis - yet another Molokai

role model - had cleaned in the last two years and returned to productivity,

partly with a grant from Evon Chinard, the founder of Patagonia.

"These lo'i are ancient," Glen told us. "When we cleared the land we found

the retaining walls still in place. Our ancestors laid them out like this."

Cleaning irrigation ditch of ancient taro field

At Halawa, the men and women of Waipahu high School, all members of the

Hawaiian club there, would weed and clean two entire taro patches, working

way past their lunch break to get the job done.

"Tell them to stop," Kathy Davis, Glen's wife, told one of their teachers,

"they are trying to do too much."

"I think that would be useless," was the reply, "they really want to finish

the job."

That was on Thursday. Today, Friday, the 'kids' were equally tenacious

in wanting to complete the task of filling the walls of the fish pond

before lunch, but at one PM their teachers called a halt.

As the students gathered in the shade of a traditional hale to eat, I

sat on the shore penning the first few paragraphs of this article. I had

been alone for only a few minutes when one of the students brought me

lunch - they always serve the kupunas before eating themselves - and,

a few moments later, I was joined by Tua Tafaloa Ka'imihaku Mahe and his

friend Sheldon Keawe Kahaleua.

"May we sit with you?" Tua asked politely. "I don 't like to see someone

sitting alone. I feel sad that they might be lonely."

Putting down my pen and notebook I tore into my tuna fish sandwich while

enjoying the company of my new friends. We launched immediately into a

discussion of the last two days of their visit on Molokai with Tua, the

most loquacious of the pair, leading the way.

"It 's a blessing for me because our ancestors made those lo'i. It's touching.

It 's hard to explain."

"Yeah," Sheldon chimed in, "and we are also learning how to be helpful

in the future by bringing back the lo'i."

"The lo'i and the fish ponds," Tua continued, "are ways of producing food

instead of just taking food. In the lo'i we weed and harvest and replant

so they always give food and the same with the fishponds - to give back

instead of just taking. It has a lot to do with the environment, taking

care of it."

"We are the new Hawaiian generation," Sheldon said, completing Tua's thought.

Did Hokule'a play a part in creating the new Hawaiian generation, I wanted

to know.

"Hokule'a and Makali'i were big steps for Hawaii," Tua told me. "I got

to go aboard Makali'i. It was awesome. I am determined to ride on one

of those canoes in the future."

The three of us chatted for some time while waiting for work to resume.

As we were gathering up our paper plates and cups to head out to the beach

once more, Tua turned to me and said, "I love being in this club. It 's

the best thing. I love being Hawaiian. I feel like my ancestors are looking

at us, and they are smiling because they see one of their grandsons doing

this. I would be here every weekend if I could."

The work continued until the sun was making good progress toward the horizon

and the entire stretch of wall - 96 about 75 feet - had been filled with

stone.

"That 's a week's work for us," Scott said. "I love this project for many

reasons," he continued, "partly because when I pick up a rock I know I

am touching the same pohaku my kupunas touched a thousand years ago. I

also like it because the work is so open. You can see it from the road.

You cannot miss it. The young guys drive past and they stop and say, "hey

brah, what you doing? I like kokua.' It is the kind of project which makes

working hard cool again."

Pausing for a moment, and perhaps in response to an earlier question I

had asked him about the impact of Hokule'a on his own life, Scott said,

"we are doing something in plain sight that demonstrates what Hawaiians

can achieve. We had lost contact with our Hawaiian-ness and now we are

getting it back. In a way," he continued, "this project is our own personal

Hokule'a."

|