|

The

Navigators

Story of the Filming

The

following was written by Stephen Thomas, author of THE LAST NAVIGATOR.

"The

Navigators," a one- hour documentary funded by Pacific Resources,

Inc., recreates one of the greatest navigational feats in human history:

the exploration and settlement of Polynesia by navigated voyages which

began more than 6,000 years ago. "The

Navigators," a one- hour documentary funded by Pacific Resources,

Inc., recreates one of the greatest navigational feats in human history:

the exploration and settlement of Polynesia by navigated voyages which

began more than 6,000 years ago.

THE

PRODUCTION TEAM

The producer of The Navigators, Dr. Sanford Low was formerly a producer/writer

for Public Television's "Odyssey" series. The film's credits

also include program consultant. Dr. Pat Kirch from the Bishop Museum;

cinematographer and director, Boyd Estus; film editor, Bill Anderson;

and associate producer and production manager, Sheila Bernard.

FILM

PRECIS

Shreds of mist shift and change, finally to reveal lush, tropical mountain

peaks. An ancient Hawaiian chant echoes: "Here is Hawaii, a child

of Tahiti." We see a 60-foot Polynesian voyaging canoe, sails brilliant

in the Pacific sunshine. These images are the first 30 seconds of the

documentary film, "The Navigators," anthropologist and film-maker

Dr. Sanford Low's documentation of the great voyages of the ancient

Polynesians. With major funding from Pacific Resources, Inc. (PRI),

and additional funding from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, and

the Hawaii Committee for the Humanities, Low tells the story of the

great voyages of Polynesia.

Ancient myths say that the Hawaiians, Tahitians and Maoris are one people,

and that they sailed across the forbidding Pacific to settle on those

widely scattered islands. If the myths have any basis in fact, then

the early Polynesians must have found their way across thousands of

miles of ocean. Polynesians must have been able to build, equip, man

and navigate vessels large enough and seaworthy enough to make these

passages of up to 3,000 miles.

To show us how such a culture would look. Low takes us to the tiny island

of Satawal, in Micronesia's Central Caroline Islands. Descended from

the same ancestors as the Polynesians, the people of Satawal still build

sea-going outrigger canoes, man them with sailors, and navigate them

throughout their widely scattered islands without maps or instruments

of any kind.

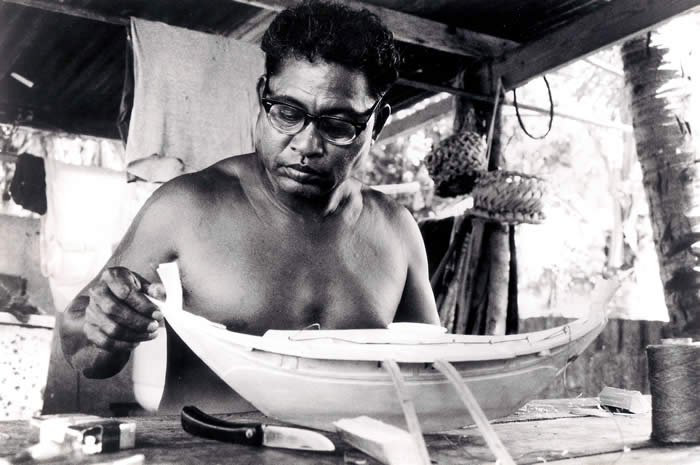

The Satawalese, and in particular, the navigator Mau Piailug, become

our guides, to whom we return again and again to bring the past alive.

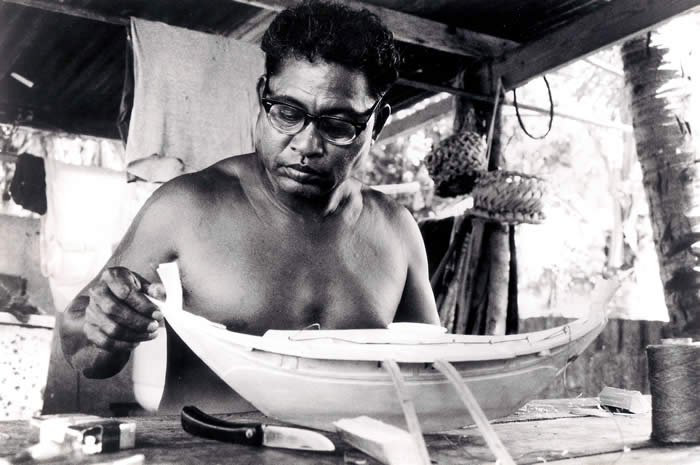

Mau Piailug creating model of his canoe

Steve Thomas Photo

Distinguished Bishop Museum scientists Drs. Patrick Kirch, Yosihiko

Sinoto and Roger Green show us how the early Polynesians ventured eastward

from their homeland in Island Southeast Asia down through the Solomon

Islands and out to Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji, the Cradle of Polynesia.

There they remained for a thousand years before making the great open

ocean voyages to the Marquesas, Tahiti, New Zealand and

Hawaii.

Back

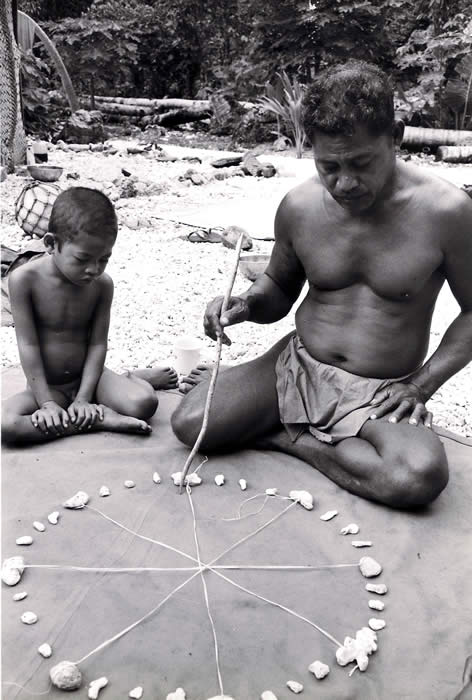

on Satawal, in scenes never before filmed, we see Pialug passing on

to his people the knowledge of his forefathers, and finally we learn

that Piailug's ancient traditions are threatened. For in the end he

tells us: "After me, I am afraid there will be no more navigators."

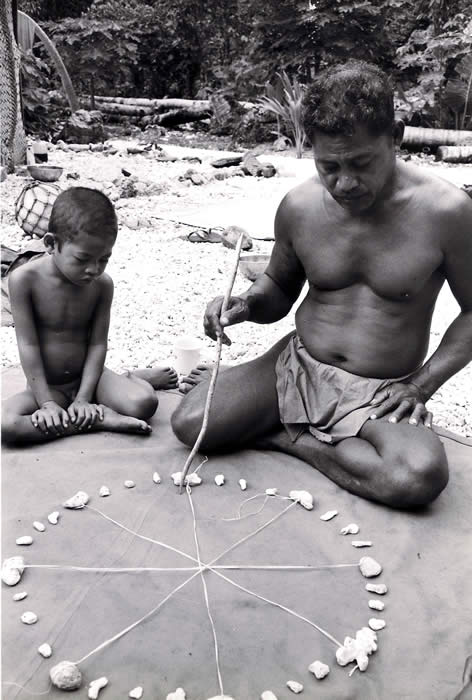

Mau Piailug using the star compass to teach navigation to his son

Steve Thomas Photo

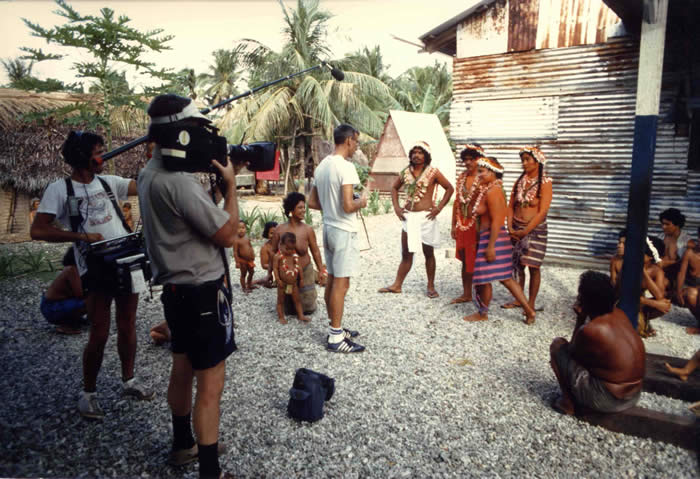

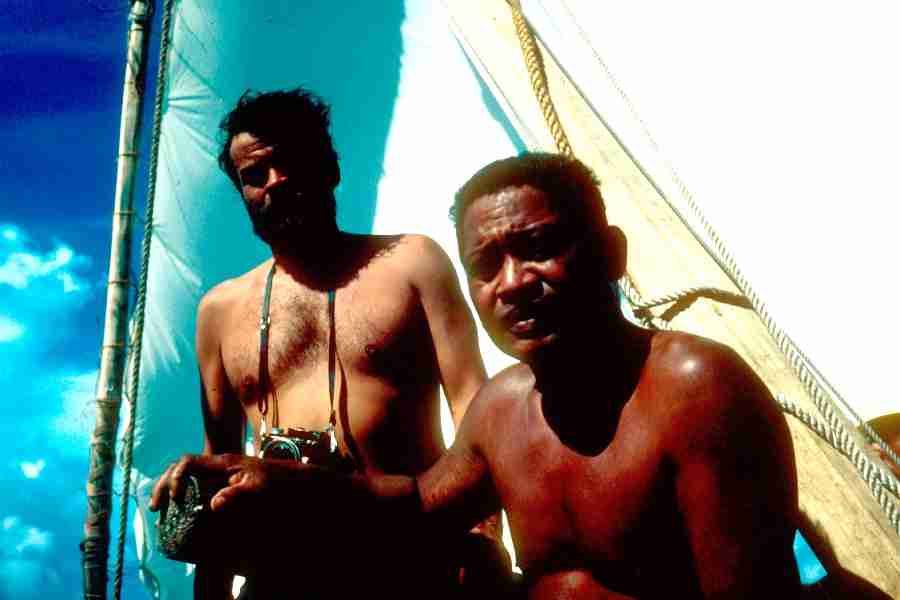

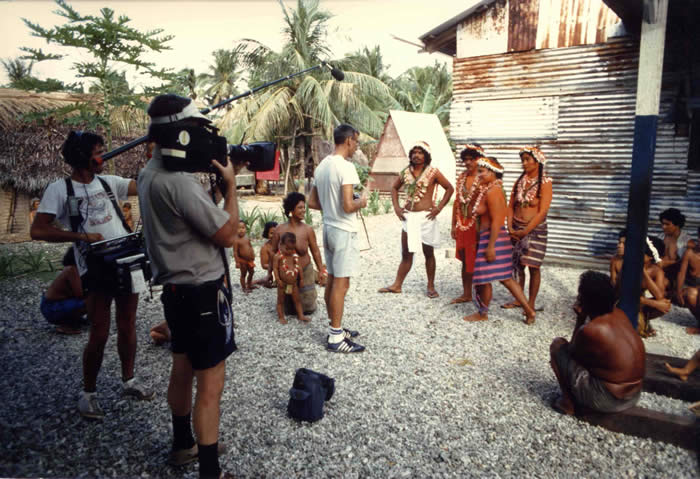

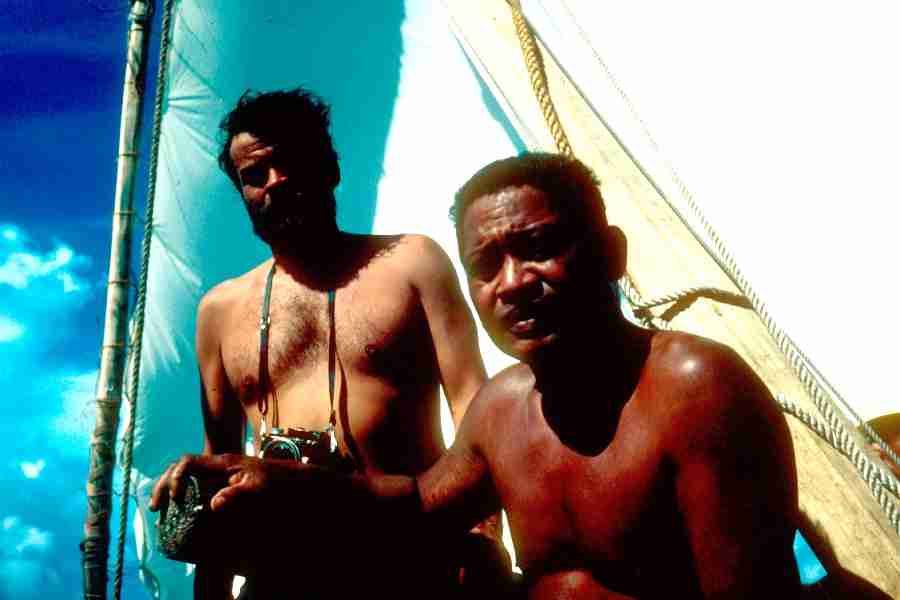

Eric Taylor (left), Boyd Estus, Mau Piailug, Translator

filming a key interview with Mau for The Navigators

POLYNESIAN

SEAFARING HERITAGE DOCUMENTED IN "THE NAVIGATORS"

Using only the wind, stars, flights of birds and other natural signs

to guide them, the ancestors of today's Polynesians sailed their hundred-foot

double-hulled canoes across a vast ocean area larger than Europe and

North America combined, on voyages that lasted for months.

In the remote Caroline Islands of the Pacific, an ocean which spans

one-fourth of the globe's circumference, are found the only remaining

non-instrument navigators, or palu. In Polynesia, despite great distance

and separation, scattered populations share an identical heritage, language

and customs.

In the past, many theories, including Thor Heyerdahl's "drift"

theory, were suggested to explain this phenomenon. Heyerdahl proposed

recently, that Polynesia was settled by colonists from South America

who drifted into the Pacific on primitive rafts. However, archaeologists,

linguists and other scientists have found evidence that confirms that

it was the remarkable navigational abilities of these early Polynesian

seafarers, first inhabitants of these islands, that allowed their culture

to spread. These new theories hold that the Polynesians sailed into

the Pacific from Island Southeast Asia, against winds and currents prevailing

in the Pacific.

Small Satawalese Proa

Dr.

Sanford Low spent three weeks on the tiny coral atoll of Satawal bringing

the past alive by recording the seafaring society that still thrives

there. Adding to "The Navigators" authenticity is island spokesperson

Mau Piailug, Satawal's last initiated palu, who takes viewers back in

history, as he skillfully sails the Hokule'a, a replica of the original

Polynesian navigators' huge canoes, 2,500 miles across the open sea.

Piailug finds his way from Hawaii to Tahiti, always on course, without

the benefit of sextant, compass or any other western navigational instrument. Dr.

Sanford Low spent three weeks on the tiny coral atoll of Satawal bringing

the past alive by recording the seafaring society that still thrives

there. Adding to "The Navigators" authenticity is island spokesperson

Mau Piailug, Satawal's last initiated palu, who takes viewers back in

history, as he skillfully sails the Hokule'a, a replica of the original

Polynesian navigators' huge canoes, 2,500 miles across the open sea.

Piailug finds his way from Hawaii to Tahiti, always on course, without

the benefit of sextant, compass or any other western navigational instrument.

In addition to celebrating one of the greatest seafaring accomplishments

in history, "The Navigators" reveals Polynesian life and travel

as it might have existed during the time of the great voyages, from

the birth of Christ to 1200 A.D.

"THE NAVIGATORS": STORY OF THE FILMING

Polynesia is a vast ocean area spanning nearly a fourth of the world's

surface, strewn with high volcanic islands and low coral atolls. The

distances between major island groups are great: Hawaii to Tahiti, 2,500

miles; Tahiti to New Zealand, 2,700 miles. Astonishingly, this huge

area is populated by people who share the same cultural heritage, with

language, customs and navigational skills that trace back to the same

origins.

The

Early Polynesian Seafarers

Historians and scientists now agree that the settlers of these widely

scattered islands came from the west, on intentionally navigated voyages

by large double-hulled canoes, in one of the most stunning seafaring

accomplishments of the human race.

The

Producer

Anyone who has stood on a seashore braced against a stiff wind must

be awed by the thought of that mass of air moving steadily over miles

and miles of cold, dark sea, and must be grateful for a solid beach

and the warm earth. Surely the captains of the ancient Polynesian voyaging

canoes must have stood thus, before they departed. Film-maker Sanford

Low knew this feeling well-that of looking out across the water, and

back in time. He knew it first as chief diver for numerous underwater

archaeological excavations in the Mediterranean Sea and later as a watch

officer aboard a Naval vessel in the Pacific. From these experiences,

and because he is part Hawaiian, Low acquired both an intellectual and

a personal interest in making "The Navigators."

Anyone who has stood on a seashore braced against a stiff wind must

be awed by the thought of that mass of air moving steadily over miles

and miles of cold, dark sea, and must be grateful for a solid beach

and the warm earth. Surely the captains of the ancient Polynesian voyaging

canoes must have stood thus, before they departed. Film-maker Sanford

Low knew this feeling well-that of looking out across the water, and

back in time. He knew it first as chief diver for numerous underwater

archaeological excavations in the Mediterranean Sea and later as a watch

officer aboard a Naval vessel in the Pacific. From these experiences,

and because he is part Hawaiian, Low acquired both an intellectual and

a personal interest in making "The Navigators."

With his own funds he began the research in Hawaii. There he met the

Bishop Museum's Dr. Yosihiko Sinoto, who had excavated an ancient village

on Huahine in the Society Islands. Among other artifacts, Sinoto unearthed

the planks, mast and a steering paddle from a big sailing canoe, or

pahi. Sinoto quickly re-buried these treasures to prevent them from

disintegrating upon exposure to the air. "While I was talking with

Yosi," Low said, "I learned that he was returning to Huahine

within a few months to re-excavate and preserve the ancient canoe pieces."

Suddenly, a vital piece of Low's story was about to unfold and he had

to find a way to film it - fast.

Filming a wedding on Satawal

Sam Low Photo

The

Funding

Low contacted PRI and explained the project. Enthusiasm was immediate

and Low was encouraged and supported by PRI's then vice president of

Public Relations, Philip H. Kinnicutt.

PRI Chairman and Chief Executive Officer James F. Gary commented, "For

a long time PRI has been looking for a project which would celebrate

the achievements of the Polynesian people and benefit the Hawaiian community.

Low's film offered us just such an opportunity."

PRI made a grant to Low for the filming phase of "The Navigators."

While carrying on with the planning, Low joined forces with KHET, the

Hawaii Public Television station, to solicit a grant from the Hawaii

Committee for the Humanities. He returned to Boston, where he received

word that the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations would also help fund the

project.

The

Team

In a matter of months Low's project had gone from initial research to

being fully funded. It was then January 1982. Low had to plan and organize

a major fuming expedition to remote sites in the Caroline Islands, Fiji,

The Society Islands and Hawaii. Moreover, he had to do it fast. The

spring sailing season in the Caroline Islands was only months away and

if he missed it he would have to postpone the shooting for a year-something

he couldn't afford to do.

Quickly Low assembled a team. Sheila Bernard, who had worked with him

on his previous PBS documentary, "The Ancient Mariners," was

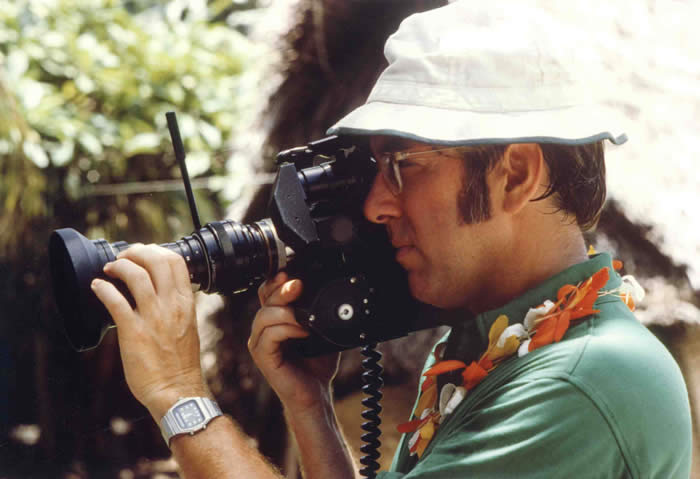

named again as associate producer and production manager. Boyd Estus,

cinematographer of the Academy Award-winning documentary, "The

Flight of the Gossamer Condor," joined the expedition as co-director

and cameraman. Bill Anderson, editor for Nova, Odyssey, World and many

other PBS projects, would edit the film.

Special

Equipment for a Remote Site

On Satawal the team would be shooting in a location 600 sea miles from

the nearest airport and serviced by freighter on a wildly irregular

schedule. Whatever they needed would have to be brought with them. The

equipment and logistic requirements were formidable for such a remote

operation and much of the equipment had to be specially designed.

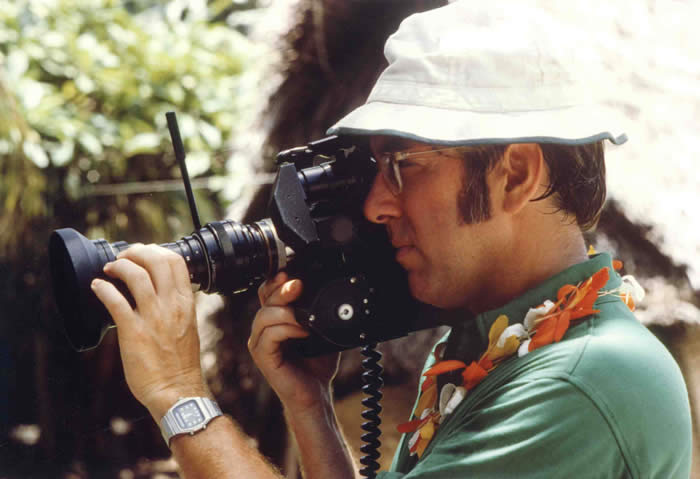

Boyd filming on Satawal

Sam Low Photo

Since they would be filming on small, wet outrigger canoes, some means

of keeping the camera dry had to Be devised. Estus designed a "parka"

for their two $40,000 Eclair 16mm cameras of the same black neoprene

divers use for their wet suits. For underwater shots Estus rented a

housing of metal pipe in which he placed a small, aircraft "gun"

camera. Since Low planned to document the traditional navigational instruction

ceremonies, which take place at night in the canoe house, he had to

bring special filming lights, filters and stands, and, as there is no

electricity on the island, a portable generator was needed. The generator

would have to be located far enough away from the filming so that the

highly sensitive sound equipment did not record its noise. Therefore,

they packed a quarter-mile of electrical cable. None of the crew spoke

Satawalese, so an interpreter would have to be found on the island.

To keep Low informed about what was being said as it was being filmed,

a complex system of radio-controlled microphones was designed by Estus

and sound-recordist Eric Taylor. The sound-recording equipment was connected

to a small radio transmitter which broadcast to the interpreter located

off-site. He translated the proceedings and transmitted them through

a special radio to Low, who, listening on headphones, could communicate

with Estus by a set of hand signals. All these systems had to be backed-up

with spares in case of a breakdown. This gear, together with 48,000

feet of film, tripods, lenses, a gyro-stabilizer for filming in heavy

seas, rubber boats, radios, camping gear, and food for the crew amounted

to some two tons-which would have to be landed on Satawal by small boat

through the surf. Estus designed and had constructed special waterproof

bags to keep their gear dry in case the boat overturned. Estus said:

"I've filmed on locations all over the world, but this one was

one of the hardest I've had to plan for-salt water is the enemy of any

delicate gear."

Low then had to charter a boat to get the crew to Satawal. The boat

would have to be big enough to carry crew and equipment and, since Satawal

has no harbor, be able to carry enough food, water and fuel to stand

offshore for the duration of the filming.

Already running behind schedule in May, Low had to find a crew who would

be willing to navigate the treacherous waters of the Caroline Islands

during typhoon season. After searching in Micronesia and Hawaii for

a month. Low finally found a 60-foot schooner-The Dorcas-captained by

Dan Wright and a crew willing to do the charter.

No sooner did the film crew arrive in Guam and stow their gear aboard

the schooner than three typhoons blew through the area, one after the

other. For two weeks they were pinned in harbor. This was the beginning

of a very tough and challenging period for Low. The delay was costing

him a thousand dollars a day. "But far more importantly,"

says Low, "I realized I had the safety often people on my hands.

If one of those typhoons had kissed us ... well . . .'

The two weeks in Guam were spent mostly in the weather hut at the U.S.

Naval Air Station. Estus installed a radio on the schooner and arranged

a network of operators to keep them informed daily of typhoon warnings

once at sea and on Satawal.

Film and camping gear arrives on Satawal - note the wave breaking on the reef. (Boyd Estus photo)

Satawal:

The Shoot Satawal:

The Shoot

On

Satawal, Low planned to film events in "real time," as they

happened. He was up at 5 each morning, trekking the village with Mau

Piailug, the navigator who became the central figure in the film. With

Piailug, he made arrangements for each day's filming. Despite interruptions

to the customary daily routine of the island, the Satawalese joined

wholeheartedly in the work of the film.

"They were remarkable!" exclaimed Low. "They skillfully

guided us through the crashing surf, helped lug our two tons of gear

ashore, fed us, housed us, held three feasts in our honor-they overwhelmed

us with their hospitality."

But it was the navigator, Mau Piailug, who took special pains to guide

the film crew every step of the way. He took Low and Estus into his

home and treated them as his sons-worthy, but needing the steady guidance

of a father.

At night Piailug schooled Low in the lore of the sky, which was handed

down to him through the generations, and which has guided him over thousands

of miles in the Pacific. Low came to realize that Piailug was fully

aware of the complexities of his film project. Having visited Hawaii

and Tahiti, and having gained national recognition for his navigation

of Hokule'a, the 60-foot replica of a Hawaiian voyaging canoe that sailed

from Hawaii to Tahiti, Piailug knew what the 20th .century was about

to overwhelm Satawal.

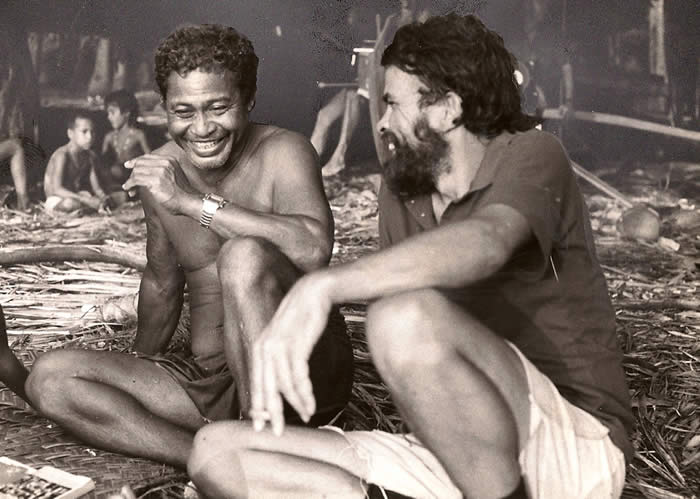

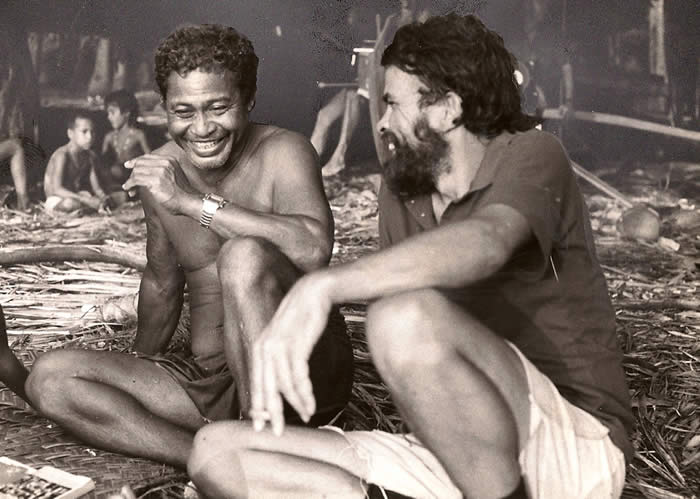

Mau and Sam take a break in Mau's canoe house

Sheila Bernard Photo

"I think Mau saw the film as a way to preserve the knowledge of

his fathers-his heritage as a navigator. On Satawal a navigator is a

teacher-more than a teacher, he is a community leader. He is bound by

an unspoken contract to pass on to the community what he knows."

The day the film crew left, Piailug told Low: "I wanted you to

make this film because the world is changing. I may be one of the last

navigators. I hope that by your film, other people, the young people

on this island and those that have never heard of the navigators, will

understand what we know."

The day the film crew left, Piailug told Low: "I wanted you to

make this film because the world is changing. I may be one of the last

navigators. I hope that by your film, other people, the young people

on this island and those that have never heard of the navigators, will

understand what we know."

(Having filmed activities on the island as diverse as a wedding, canoe-building,

and a night-time canoe trip to a neighboring island, the film crew departed

on August 15, 1982 to complete the filming on Fiji and Hawaii. Three

weeks after Mau Piailug said goodbye, the production phase of the film

was completed. Low's work, however, was far from finished.

Post-Production

Back in Boston the footage was processed and printed, and the labor

of editing began. "This was the first time I was really worried,

said Low. I was suffering from a bad case of producer's

hangover. The images we came back with didn't match my preconceptions."

Editor Bill Anderson, however, fresh to the project, didn't share Low's

worries. "The images took me to a place and time I'd never seen

before," he said "I knew we had a good film on our hands."

After

six weeks of editing the film began to reveal itself. Low put it this

way: "It was as if we had a 200-pound ballerina on our hands: she

could dance-not well-but she was dancing, and she had to lose weight.

We had to do was put her on a diet."

"The

Navigators," reveals the art and science of Polynesian navigation

as never portrayed before. Some of the material, such as the teaching

sessions in the canoe house, have never been filmed. Other sequences

show breathtaking aerial and underwater shots. Low weaves the ethnographic

originality and physical beauty of the island setting into the story

of how the vast reaches of the Pacific were settled.

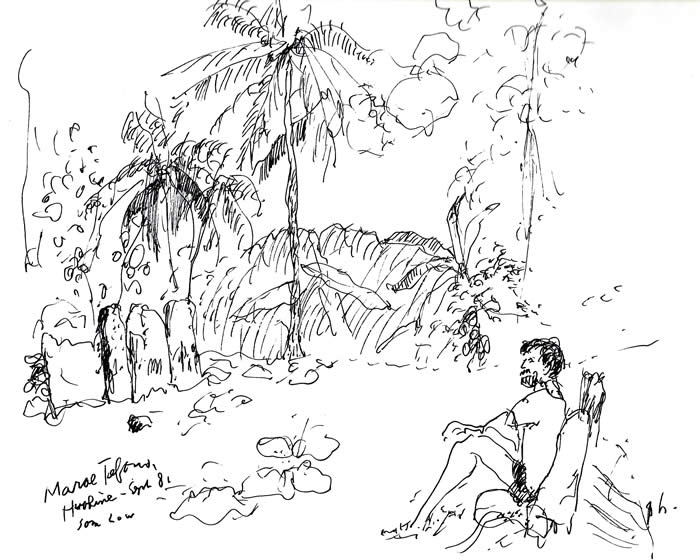

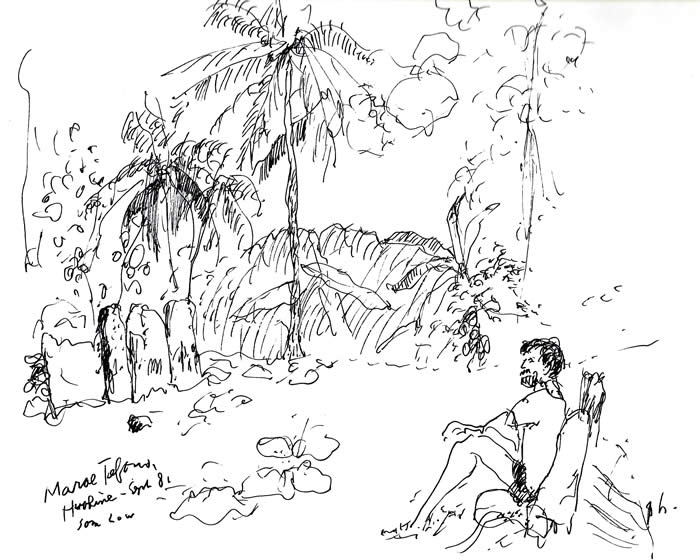

Sam resting at a marae (temple) on Huahine Island during filming of The Navigators. Sketch by cameraman Peter Hoving. |

"The

Navigators," a one- hour documentary funded by Pacific Resources,

Inc., recreates one of the greatest navigational feats in human history:

the exploration and settlement of Polynesia by navigated voyages which

began more than 6,000 years ago.

"The

Navigators," a one- hour documentary funded by Pacific Resources,

Inc., recreates one of the greatest navigational feats in human history:

the exploration and settlement of Polynesia by navigated voyages which

began more than 6,000 years ago.

Dr.

Sanford Low spent three weeks on the tiny coral atoll of Satawal bringing

the past alive by recording the seafaring society that still thrives

there. Adding to "The Navigators" authenticity is island spokesperson

Mau Piailug, Satawal's last initiated palu, who takes viewers back in

history, as he skillfully sails the Hokule'a, a replica of the original

Polynesian navigators' huge canoes, 2,500 miles across the open sea.

Piailug finds his way from Hawaii to Tahiti, always on course, without

the benefit of sextant, compass or any other western navigational instrument.

Dr.

Sanford Low spent three weeks on the tiny coral atoll of Satawal bringing

the past alive by recording the seafaring society that still thrives

there. Adding to "The Navigators" authenticity is island spokesperson

Mau Piailug, Satawal's last initiated palu, who takes viewers back in

history, as he skillfully sails the Hokule'a, a replica of the original

Polynesian navigators' huge canoes, 2,500 miles across the open sea.

Piailug finds his way from Hawaii to Tahiti, always on course, without

the benefit of sextant, compass or any other western navigational instrument. Anyone who has stood on a seashore braced against a stiff wind must

be awed by the thought of that mass of air moving steadily over miles

and miles of cold, dark sea, and must be grateful for a solid beach

and the warm earth. Surely the captains of the ancient Polynesian voyaging

canoes must have stood thus, before they departed. Film-maker Sanford

Low knew this feeling well-that of looking out across the water, and

back in time. He knew it first as chief diver for numerous underwater

archaeological excavations in the Mediterranean Sea and later as a watch

officer aboard a Naval vessel in the Pacific. From these experiences,

and because he is part Hawaiian, Low acquired both an intellectual and

a personal interest in making "The Navigators."

Anyone who has stood on a seashore braced against a stiff wind must

be awed by the thought of that mass of air moving steadily over miles

and miles of cold, dark sea, and must be grateful for a solid beach

and the warm earth. Surely the captains of the ancient Polynesian voyaging

canoes must have stood thus, before they departed. Film-maker Sanford

Low knew this feeling well-that of looking out across the water, and

back in time. He knew it first as chief diver for numerous underwater

archaeological excavations in the Mediterranean Sea and later as a watch

officer aboard a Naval vessel in the Pacific. From these experiences,

and because he is part Hawaiian, Low acquired both an intellectual and

a personal interest in making "The Navigators."

Satawal:

The Shoot

Satawal:

The Shoot

The day the film crew left, Piailug told Low: "I wanted you to

make this film because the world is changing. I may be one of the last

navigators. I hope that by your film, other people, the young people

on this island and those that have never heard of the navigators, will

understand what we know."

The day the film crew left, Piailug told Low: "I wanted you to

make this film because the world is changing. I may be one of the last

navigators. I hope that by your film, other people, the young people

on this island and those that have never heard of the navigators, will

understand what we know."