Sam Low

Just another WordPress site

Lau Lima – a laying on of hands

Lau Lima

A Laying on of Hands

By Sam Low

Sailing Hokule’a with a crew of volunteers over routes not traversed for perhaps a millennium has presented many crises. One such occurred in May of 1997, when Nainoa hired a surveyor to inspect the canoe prior to its voyage to Rapa Nui.

A marine surveyor is empowered to say whether or not a vessel is seaworthy. He uses simple tools, a trained eye, a pocketknife and a rubber mallet. With his knife he probes for dry rot, a kind of virus that reduces wood to dust, although not obviously so to the naked eye. Poking in strategic places tells the story. If the knife goes in easily, the wood is rotten. Banging on the hull with a mallet may produce discordant notes to a surveyor’s ear, another sign of problems.

After a few hours of poking and banging on that May afternoon, the surveyor made his report: “the canoe is rotten,” he said. “I cannot certify her seaworthiness. I suggest you think about putting her in a museum.” The pronouncement was a surprise but not a shock. Nainoa had seen places where there was dry rot, but the canoe had taken him safely across many oceans and had demonstrated more than seaworthiness, she had shown her mana, her strength of spirit. Retiring Hokule’a to a museum was not an option.

“I need two lists,” Nainoa said to the surveyor, “I need a list of what’s wrong with her, and a list of what to do to make her even stronger than when she was built.”

The what-to-do list was long. Two of the wooden iakos had to be replaced – an onerous job but not exceedingly so. The hull was another matter. Wooden stringers run lengthwise from bow to stern, providing strength. There are five such stringers on each side, many of them rotten. The job of fixing all these problems fell to Bruce Blankenfeld.

In September, the canoe went into dry-dock. Perhaps “dry-dock” is a misnomer because it conjures a picture of Hokule’a in a mammoth shipyard cofferdam. Hokule’a’s dry-dock was a shed in a decrepit section of the Port of Honolulu. Nearby was a junkyard with a tall fence and barking dogs, a pile of sand for making cement, a small marina, a few boatyards that did not appear very busy. Bruce set about finding workers.

“It’s easy to find people when you’re ready to go sailing but when you need them to maintain the canoe it can be pretty difficult. I had a group of young folk come down at the beginning of September and tell me they wanted to help. I said, ‘well, it’s pretty easy to do that. All you have to do is show up.’ But after they saw all the work that was going on, they never returned.”

What the prospective workers saw was nasty. Young men and women squirmed through hatches only slightly wider than their shoulders where they toiled for hours, in Stygian gloom, amidst fiberglass dust and the odor of polyvinyl resin. They excised the rotten stringers. They fitted new sections of wood. Then they “sister-framed” each stringer by adding two new pieces of wood, one on top and one on the bottom. Triangular wedges of foamed plastic followed for yet more strength and to “fair” the stringers into the hull. They sanded all this smooth and laid layers of glass fiber over it. They pushed resin into the fiber’s mesh. When it hardened, the process was repeated. Then again. Three coats of resin; then two coats of paint. Meanwhile, other volunteers sanded off the hulls’ gel-coat. Fiberglass dust veiled the canoe, clogging the pores of exposed skin. For eight months, Bruce found himself down at dry-dock at odd hours inspecting the work. Seeing his crew laboring over the canoe was like seeing a resurrection.

“Even though the work was hard, there was always a lot of energy. We saw progress every day. People are working together in the same place. It’s usually dry and, compared to sailing the canoe, working conditions are luxurious. There are fits and starts, but everything seems to come together all right in the end. You are working on something that is very beautiful. You are touching the past with sandpaper and saws and rope lashings.”

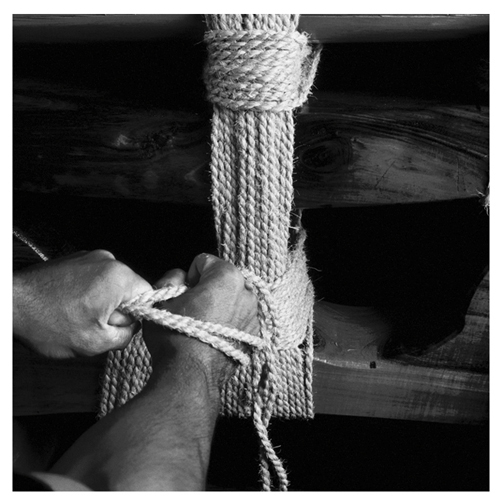

Bruce supervised his crew as they stripped the canoe’s twin masts and brushed on eight coats of varnish and sanded each to the texture of baby-skin. Then they renewed five miles of rope lashings a few feet at a time. They ripped off deck planking, replaced and relashed it. The canoe received new iakos, new splashboards, and new manus fore and aft. She received stanchions, catwalks, hatches, and wiring for running lights and emergency radios.

An army of volunteers donated thousands of man and woman hours to Hokule’a’s rebirth, a laying on of hands that expressed their deep commitment to the canoe and what she meant to them. They came from all walks of life. There is Russell Amimoto, for example, nineteen years old, a professional house painter and volunteer canoe lasher. He has served Hokule’a for three years. There is Kamaki Worthington, twenty-six, a teacher, fiberglasser, also a veteran of three years service. There is Kiki Hugo, in his forties, a cross country trucker who spends long months on the mainland driving from San Francisco to the Bronx, the Bronx to San Francisco, until he earns enough money to return home to Oahu. He is a kupuna, an elder crewmember with twenty-five years service. There is Lilikala Kamalehiva, fortyish, college professor, chair of the department of Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawaii, Hokule’a’s chanter and master of protocol; Wally Froiseth, early seventies, once Hawaii’s most famous big-wave surfer, now captain of the pilot boat of the Port of Honolulu; Jerry Ongies, early sixties, retired Army officer, ex-manager Dole Pineapple plant, boat builder, cabinet maker, canoe fabricator. This list of workers is an extremely small selection of the hundreds who donated their time to the canoe. The complete list would fill a book. If you were to ask these people why they have so freely given of themselves to the canoe they will provide a variety of reasons, unique to each of them, but there will also be a common response similar to what Nainoa once told an audience of legislators when they asked him why they should fund Hokule’a and her voyages.

“We must sail in the wake of our ancestors,” he told them, “to find ourselves.”

Finally, on the last week in March, the work was finished. The surveyor returned with his knife, his mallet and his well trained eye and certified the canoe “Lloyds A-1,” nomenclature used by the world’s largest insurer of watercraft to signify complete readiness for sea. A few days later, the canoe was launched. Among the men and women who tended Hokule’a as a giant crane lifted her from her cradle and laid her upon the ocean was Bruce Blankenfeld.

“The mana in this canoe comes from all the people who have sailed aboard Hokule’a and cared for her,” Bruce said, looking out over the crowd that had come down for the launching. “I think of the literally hundreds of people who have come down and given to the canoe when she was in dry dock. I think of everyone who has shared similar work since she was first launched in 1975, those who have sailed aboard her, the men and women in all the islands we have visited who hosted us. All of this malama – this laying on of hands – adds to the mana of the canoe. It is intangible but it is alive and well.”