|

Voyages

of Awakening, 25 years of Höküle'a

By Sam Low

First Finalist, Society of Professional Journalists, Hawaii Chapter,

Feature Writing - Long Form, 2001; Kahili Award, Hawaii Visitors Bureau

award for best article celebrating Hawaiian culture, 2000.

Hana Hou Magazine

Photos

by Sam Low

In the quarter-century since she was first launched on March 8,

1975, the voyaging canoe Höküle'a, her dedicated crews and the multitude

of others who have contributed to her success have proved the incredible

prowess of the Polynesian seafaring heritage many times over. But even

more importantly, they have helped to revive an ancient culture and

reunite a diverse and widespread people. Over the last twenty-five years,

a vision has evolved among the canoe's vast family - one that finds

in the traditions of Polynesia universal lessons that may guide us all

in the new millennium. This is the story of that family and that vision.

From Captain Cook's Quandary, a Dream is Born

In 1778, when Captain James Cook discovered that the people of Hawai'i

were of the same race as those he had encountered throughout Polynesia,

he asked: "How shall we account for this Nation having spread itself

to so many detached islands?" How indeed could a stone-age people have

navigated and explored a third of the earth's surface without instruments

or charts? How could they have built powerful sailing vessels without

metal nails or canvas sails?

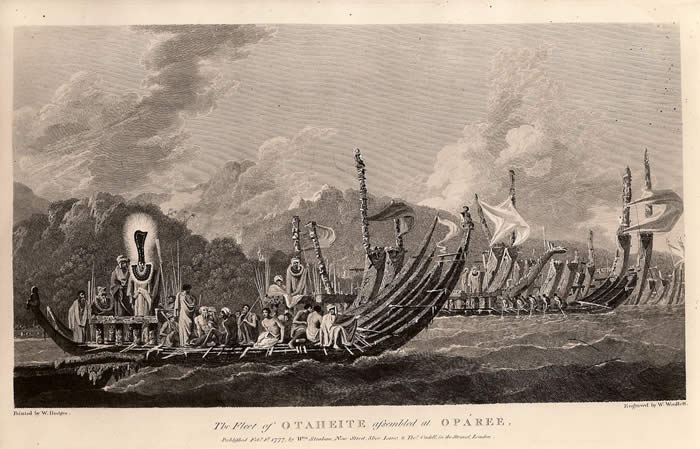

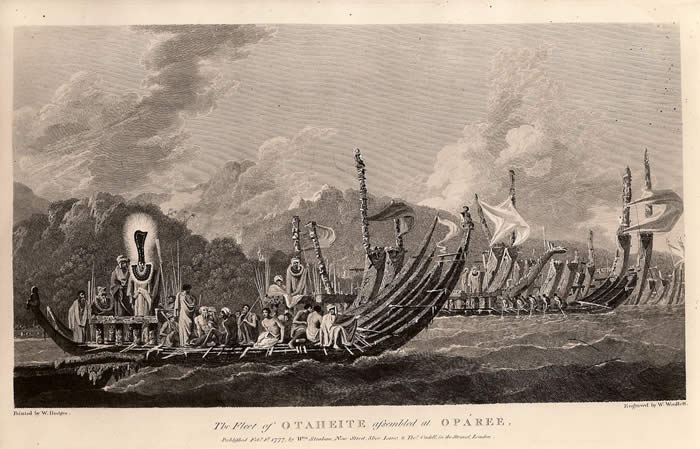

Polynesian war canoes at Tahiti sketched by Cook's artist

Some early scholars suggested that South American Indians could possibly

have settled the Polynesian islands simply by drifting westward on crude

rafts, riding the prevailing currents and winds. In 1947, Norwegian

explorer Thor Heyerdahl set out from Peru to test this theory aboard

his famous balsa-wood raft, Kon Tiki. Despite many dire predictions

that the simple raft would surely be smashed to pieces in the open ocean,

Heyerdahl and his crew eventually managed to make landfall in the Tuamotu

Islands, just east of Tahiti, indicating to some that at least part

of Polynesia could have been settled this way. But by the late 1960s,

mounting scientific evidence began to point toward a much different

source of origin for the ancient Polynesians. Increasingly, archaeological

and linguistic studies indicated that the true Polynesian homeland lay

to the west - in the area of Southeast Asia. This meant that to settle

the islands they must have sailed against the powerful prevailing tradewinds

and currents, which in turn suggested that they possessed highly efficient

oceangoing vessels and a vast cultural storehouse of navigational knowledge.

Some scholars at the time continued to maintain that any such settlement

must have occurred purely by chance, perhaps by fishing canoes that

had been accidentally blown to sea. But this hardly seemed to explain

the incredible dispersal of the Polynesian people over immense distances

of the Pacific. And furthermore, ancient Polynesian chants and myths

told clearly of powerful canoes and great navigators. Could the myths

be true? In the early 1970s, three men decided to find out.

|

"Höküle'a

came from the dream of three people," recalls Polynesian Voyaging

Society director and head navigator Nainoa Thompson. "Dr. Ben Finney,

an anthropologist from Santa Barbara; Herb Kawainui Kane, an artist

of Hawaiian descent; and writer and community leader Tommy Holmes,

a man who truly loved the sea. They said, 'We want to test all these

theories about how Polynesia was settled, and the only way to do that

is to get out of the four walls of the academic world and build a

voyaging canoe and sail it to Tahiti.'"

Finney, Kane and Holmes founded the Polynesian Voyaging Society in

1973. "We made a great team," says Kane, "because we approached the

Höküle'a project from different points of view. Ben was the scientist,

Tommy was the waterman and adventurer, and I approached it from the

cultural point of view."

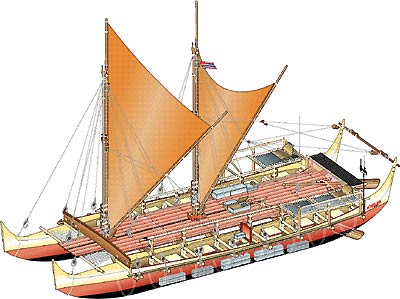

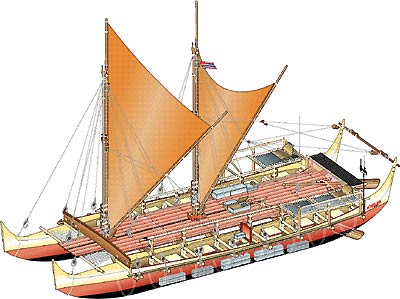

Although the PVS founders wanted to use traditional materials and

tools to construct the canoe, they realized that the process would

become too time-consuming as the builders tried to relearn the arts

of working with materials such as koa-wood hulls, woven lauhala sails

and sennit lashing. Instead, the hulls were constructed out of plywood

and fiberglass; the sails were made from canvas; and the lashings

were done with synthetic cordage. However, Höküle'a's creators strove

to approximate the shape and weight of a traditional canoe to create

a "performance-accurate" replica that handled as much like the ancient

Polynesian voyaging canoes as was considered possible.

The canoe was named Höküle'a, or "Star of Gladness," after the Hawaiian

name for the star Arcturus, which reaches its zenith directly over

Hawai'i and was likely to have been used as a prime navigational marker

by ancient wayfinders seeking to locate the Islands. Kane recalls

how the name first came to him: "One exceptionally clear night I stayed

up quite late, star chart in hand, memorizing stars and their relative

positions. When I finally went to sleep, I dreamed of stars, and my

attention was attracted to Arcturus. It appeared to grow larger and

brighter, so brilliant that I awoke. I turned on my reading light

and wrote 'Höküle'a.' The next morning, I saw the notation and immediately

recognized it as a fitting name for the canoe. As a zenith star for

Hawai'i, it would indeed be a star of gladness if it led to landfall.

The name was proposed at the next board meeting and adopted."

On March 8th, 1975, Höküle'a was launched. Its mission was to test

the theory that the ancient Polynesians were brilliant seafarers who

intentionally explored the Pacific, but how would the vessel be navigated

in the ancient way - without charts or instruments? Although the traditional

arts of navigating had been lost in Polynesia, a handful of seafarers

in the remote islands of Micronesia still found their way across trackless

ocean expanses using only the arc of stars, the wave patterns and

the flight of birds. One of them, Mau Piailug from the tiny island

of Satawal, agreed to guide Höküle'a to Tahiti.

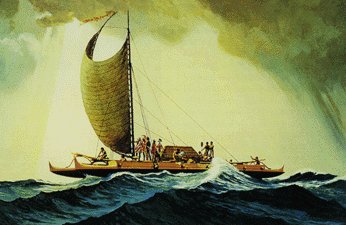

Hokule'a off Diamond Head

On

May 1, 1976, Höküle'a left Hawai'i on her maiden voyage. Nainoa, who

flew to Tahiti to serve as a crew member on the return trip, remembers

the moment of arrival when Höküle'a reached Pape'ete thirty-three

days later: "I watched the canoe enter Pape'ete Harbor. Seventeen

thousand people came down - over half the population of the island.

The canoe got to the black-sand beach, and so many children got on

that it sank the stern. People couldn't see, so they climbed into

the trees. It was a spontaneous, innate reaction by a people who had

maintained their language and their genealogy, who understood who

their great navigators were. They knew about the great canoes, but

they did not have such a canoe. So when Höküle'a entered the bay she

was a powerful symbol that reminded them of the greatness of their

culture and their heritage - and therefore themselves. It was the

beginning, I think, of cultural revival and the renewal of the Polynesian

people."

Lost

at Sea: A Crisis and a Turning Point

In 1978 - with insufficient preparation and without Mau on board -

Höküle'a again left for Tahiti. But the voyage had hardly begun when

disaster struck: During rough weather in the middle of the night,

the canoe capsized between O'ahu and Lana'i. In a heroic effort, lifeguard

and big-wave surfer Eddie Aikau, one of Hawai'i's most experienced

watermen, tried to paddle to shore on a surfboard to get help. He

was never seen again.

Eddie's loss was a devastating blow. For many, he represented the

best of what it meant to be Hawaiian. "Eddie's death split the community,"

Nainoa remembers. "Some of us wanted to stop voyaging, but some of

us thought that if we did his death would have no value. I believed

that voyaging inspired our Hawaiian community and gave us all pride.

I believed we had to continue. It was Eddie's inspiration that kept

us together during those hard times."

Eventually, the PVS reorganized and recommitted itself to the renewal

of culture through voyaging, but only if it could be done safely.

The Society turned to Mau and asked him to share his sacred knowledge

of sailing and navigation, and for the next two years Mau helped prepare

a crew for another voyage to Tahiti. But this time, the canoe would

be guided by a Hawaiian - Nainoa.

"Mau trained us like his grandfather trained him," Nainoa recalls.

"He took us on the ocean like children, becoming our father and mother

at sea. We had very few formal lessons; the learning really came by

being close to him - looking at the things he looks at, feeling the

things he feels. Even though I'm now able to guide the canoe on my

own, I'm still his student. He is the only master navigator."

In 1980, Nainoa successfully guided Höküle'a to landfall in Tahiti.

By this time, the canoe had become a powerful symbol of Polynesian

renewal. Rediscovering the ancient arts of seafaring helped stimulate

a similar renaissance in language, dance, poetry, architecture, spirituality,

traditional medicine - all the core cultural values of a native island

people.

"The canoe brought back our traditions of the sea," says navigator

Bruce Blankenfeld. "There were people who knew about canoe making,

but they had gone underground after the Western influence came in.

But once we began to sail, we began to rediscover it all."

The Voyage of Rediscovery

In 1985, Höküle'a embarked on a new mission. Her crew would traverse

most of Polynesia - a two-year, 16,000 mile odyssey - to carry the

message of cultural revival throughout the great Polynesian Triangle.

The canoe followed ancient migratory routes - from Hawai'i to the

Society Islands, the Cooks, New Zealand, Tonga, Samoa and back home

via Aitutaki, Tahiti and Rangiroa in the Tuamotu Archipelago. The

voyage eastward from Samoa to Tahiti retraced the first great migratory

steps believed to be have been taken by Polynesians at about the time

of Christ. It was also, once again, an opportunity to prove the mettle

of the Pacific's traditional seafarers.

"Thor Heyerdahl had said that it was impossible to get from western

Polynesia to Tahiti because of the easterly trade winds," says Nainoa.

"He thought that the old canoes could not tack against them. We set

out to prove him wrong. We trained for two years, we cut down our

crew and we cut down our rations of food and water. We made the canoe

light so that it would perform better, then we went to Samoa and waited

for the weather."

Heyerdahl and other scholars who thought it impossible for Polynesians

to sail against the winds and currents failed to consider that every

summer westerly winds blow with some regularity across the western

Pacific, and episodically extend into the eastern Pacific. Furthermore,

during El Niño events, the trade winds falter and more prolonged westerlies

blow across Polynesian waters. Höküle'a waited for one of these westerlies

and blazed across the distance from Samoa to Tahiti.

"We had planned for a thirty-five-day voyage, the longest ever," Nainoa

recalls. "And we did it in seven days."

Hawai'iloa and Te Aurere - Marquesas

A

New Canoe - Hawai'iloa

Höküle'a had been built as a "performance replica" - shaped like an

ancient canoe but crafted from modern materials. Now that she had

proved her abilities beyond a doubt, the question became: How would

a canoe built from traditional materials perform? In 1990, the PVS,

in partnership with Bishop Museum's federally funded Native Hawaiian

Culture and Arts Program, decided to find out by building a new voyaging

canoe entirely of natural materials. She would be named Hawai'iloa

after the mythic fisherman who, according to chants and legends, was

the first discoverer of the Islands. The original intention was to

fashion Hawai'iloa 's hulls from koa, a Hawaiian native hardwood that

was believed to have been used in building the Islands' ancient voyaging

canoes. But PVS teams explored Hawai'i's forests for nine months without

finding a single tree that was big enough to use.

"The failure to find a koa log was a turning point for all of us,"

remembers Myron "Pinky" Thompson, Nainoa's father and president of

the PVS. "For a decade and a half we had focused our attention on

the sea. Now it was time to care for our land. We realized that our

culture and our planet cannot thrive unless our environment is healthy."

Since that moment, the PVS has focused a major effort on reforestation

and environmental education. Fortunately, there was another historical

source of wood for canoes: logs that drifted to Hawai'i from the Pacific

Northwest. In an extraordinary act of kindness, the native people

of southeast Alaska gave two 400-year old spruce logs to the Society

to build Hawai'iloa. The gift was arranged by a friend of Herb Kane's,

a Native Alaskan leader named Judson Brown.

"Judson taught us so much," Nainoa remembers. "The Alaskan people

care for their environment because they understand that the resources

of the natural world are sacred gifts. When he presented us with the

trees, he said, 'Our trees are part of our family, they are cherished

like our children. We will give you two of our children to build a

canoe that will carry your culture.'"

Building Hawai'iloa provided a way for an even larger Hawaiian community

to join in reviving the ancient traditions. Under the watchful eye

of master canoe builder Wright Bowman Jr., volunteer shipbuilders,

lashers, sailmakers, painters, caulkers and others labored more than

500,000 man-hours to breathe new life into the two giant spruce logs.

"Wright stepped forward to guide us and care for us with great aloha,"

says Bruce Blankenfeld. "Under his tutelage a new family of the canoe

was born." In 1993, after three years of arduous labor, Hawai'iloa

took to the sea. But even before she ever set sail, she had already

represented a new level of community involvement; she had played an

essential role in sharpening the Voyaging Society's appreciation for

the fragility of Hawai'i's environment; and she had cemented a deep

friendship between Hawaiians and the native peoples of southeast Alaska.

Canoes Across the Pacific

In 1992, stimulated partly by Höküle'a's epic voyages, the Sixth Pacific

Arts Festival in Rarotonga was dedicated to Polynesia's great voyaging

heritage. An invitation went out to islanders throughout the Pacific

to sail to the festival aboard replicas of their own ancestral canoes.

"That challenged everybody," Nainoa remembers, "so different island

groups each decided to build their own canoes. When they called Hawai'i

to ask for assistance, it was a great opportunity for us to pay back,

in a small way, the kindness that had been shown to us all through

the South Pacific. It also gave us the opportunity to move into a

new area - education."

Höküle'a sailed to Rarotonga for the festival, where she was joined

by sixteen other canoes from islands spread throughout the Pacific.

Now fully committed to a mission of education, the PVS created a unique

program called "The Voyage for Education" to accompany Höküle'a's

return from Rarotonga. Daily live reports broadcast on KCCN Hawaiian

Radio gave information about the canoe's position, weather conditions,

sailing strategy, navigational techniques and life on board. There

were also interactive links with a state-wide educational television

program and with students at the University of Hawai'i at Mänoa. Two

days after leaving Rarotonga, Höküle'a established a historic, three-way

satellite link with the space shuttle Columbia, which was orbiting

the earth, and a panel of schoolchildren in a TV studio at the University

of Hawai'i. The students posed questions alternately to the crew of

the canoe and the shuttle. One student asked, "What are the similarities

and differences between canoe and space travel?" Astronaut Charles

Lacy Veach, who grew up in Honolulu, answered: "Both are voyages of

exploration. Höküle'a is in the past, Columbia is in the future."

Nainoa added from the canoe: "We feel both are trying to make a contribution

to mankind. Theirs is in science and technology. Ours is in culture

and history. Columbia is the highest achievement of modern technology

today, just as the voyaging canoe was the highest achievement of technology

in its day."

Cook Island canoe off Honolulu

Nä 'Ohana Holo Moana - "The Voyaging Family of the Vast Ocean"

The pace of Polynesian cultural revitalization continued as new voyaging

canoes were built - the Makali'i in Hawai'i, two in Tahiti, two in

the Cook Islands and one in Aotearoa (New Zealand). In 1995, all three

of the Hawaiian canoes met with others from around Polynesia at the

island of Ra'iatea, near Tahiti, for a ceremony to reopen an ancient

marae (temple) of navigation called Taputapuatea. This was particularly

significant since the temple, which lies at the symbolic center of

the Polynesian Triangle, was historically a great gathering place

for the canoes and navigators of many islands. More than 600 years

before, however, a powerful kapu (religious taboo) had been placed

on the marae after a Maori chief was killed there. The profoundly

emotional ceremony at the marae removed that kapu and brought about

a blessing once again for a united voyaging community of all Polynesians.

Soon after the ceremony, six canoes - Höküle'a, Hawai'iloa and Makali'i

from Hawai'i; Te Au o Tonga and Takitumu from Rarotonga; and Te Aurere

from Aotearoa - left the Marquesas Islands for Hawai'i, following

a traditional voyaging route. It was the first time in hundreds of

years that a fleet of Polynesian sailing canoes had journeyed together

- a new 'ohana (family) of the ocean star paths. Almost immediately

after arriving home in Hawai'i, Höküle'a and Hawai'iloa were shipped

to Seattle for a "Voyage of Thanksgiving" along the Pacific coast

of the North American continent. Höküle'a sailed south along the West

Coast, reaching thousands of Hawaiians who no longer lived in the

Islands, but longed to share in the canoe's legacy. Hawai'iloa sailed

north to thank the native peoples of Southeast Alaska for their gift

of trees for her hulls. This was an opportunity for the PVS to give

back to them, but at each stop the canoe and crew were overwhelmed

with gifts and kindness. Soon after the ceremony, six canoes - Höküle'a, Hawai'iloa and Makali'i

from Hawai'i; Te Au o Tonga and Takitumu from Rarotonga; and Te Aurere

from Aotearoa - left the Marquesas Islands for Hawai'i, following

a traditional voyaging route. It was the first time in hundreds of

years that a fleet of Polynesian sailing canoes had journeyed together

- a new 'ohana (family) of the ocean star paths. Almost immediately

after arriving home in Hawai'i, Höküle'a and Hawai'iloa were shipped

to Seattle for a "Voyage of Thanksgiving" along the Pacific coast

of the North American continent. Höküle'a sailed south along the West

Coast, reaching thousands of Hawaiians who no longer lived in the

Islands, but longed to share in the canoe's legacy. Hawai'iloa sailed

north to thank the native peoples of Southeast Alaska for their gift

of trees for her hulls. This was an opportunity for the PVS to give

back to them, but at each stop the canoe and crew were overwhelmed

with gifts and kindness.

"When we arrived in Alaska, the people there realized instinctively

that the canoe was a symbol of renewing a culture," Nainoa remembers.

"We went there to thank them, but instead they thanked us. I will

never forget the words spoken by Judson Brown: 'We gave you wood for

your canoe, but you gave us a dream.' I realized then that the native

people of Alaska and the people of Hawai'i may be culturally different,

but we are also very similar. We both respect our natural world, and

we're both struggling to survive in a modern world and yet maintain

our traditions, the foundation of who we are."

A

Quarter-Century of Achievement A

Quarter-Century of Achievement

By now, it has become abundantly clear that the voyaging process is

much more than a way of finding landfall or sailing a canoe. It is

a method for achieving success that embodies universal human values

- vision, planning, discipline, courage and aloha. What began as a

scientific experiment to build a replica of a traditional canoe for

a one-time sail to Tahiti has become a catalyst for a generation of

cultural renewal.

"When I look at Höküle'a I see a community," says Nainoa. "I see visions

of Eddie Aikau - of sacrifice. I see great joy in children. I see

it pulling a people together. I see sheer beauty in its lines and

images. I see it being a part of this new vision for Hawai'i. I see

the canoe teaching us deep lessons."

Höküle'a, Hawai'iloa, Makali'i and the other canoes throughout Polynesia

have joined men and women of all races and ethnic groups in a common

endeavor to revive a profound and ancient tradition. Over the last

twenty-five years, the family of the voyaging canoe has grown to more

than 525,000 men, women and children who have participated in PVS

programs of education, training, research and dialogue.

And the incredible voyage continues. In 1996, PVS joined with The

Queen's Health Systems in a program to improve Native Hawaiian health.

For ten months, Höküle'a sailed throughout the Islands - a 2,000-mile

journey, during which more than 25,000 schoolchildren and community

members visited or sailed aboard the canoe. "The message of the voyage,"

says PVS President Pinky Thompson, "was that we cannot have a healthy

culture unless we improve the physical health of our people. Taking

responsibility for our own health - and, ultimately, the health of

our planet - is not just a problem for Hawaiians but a problem for

all of us."

The PVS's vision for a healthy Island future has since evolved into

a far-reaching educational program called Mälama Hawai'i, or "Caring

for Hawai'i," which Nainoa himself explains in a heartfelt essay on

Page 41 of this special voyaging edition of Hana Hou! And, as the

new millennium dawns, Höküle'a has only just returned from what many

consider to be her most daring adventure: the epic upwind voyage to

the isolated island of Rapa Nui at the extreme eastern end of the

Polynesian Triangle. A personal account of that voyage begins on Page

34. For those of us whose lives have been touched and transformed

by the majesty of Höküle'a, her ultimate lesson has been this: that

humankind's future survival on planet Earth requires that we all care

for each other and our natural environment. As navigator Chad Baybayan

puts it: "The land and the sea and all life on our planet are interconnected.

So if we take care of even the smallest portion of land, or ocean

or the smallest creature, we take care of ourselves."

Many thanks to Dennis Kawaharada, whose Internet timeline provided

the framework for this article.

~ SHL

|

Soon after the ceremony, six canoes - Höküle'a, Hawai'iloa and Makali'i

from Hawai'i; Te Au o Tonga and Takitumu from Rarotonga; and Te Aurere

from Aotearoa - left the Marquesas Islands for Hawai'i, following

a traditional voyaging route. It was the first time in hundreds of

years that a fleet of Polynesian sailing canoes had journeyed together

- a new 'ohana (family) of the ocean star paths. Almost immediately

after arriving home in Hawai'i, Höküle'a and Hawai'iloa were shipped

to Seattle for a "Voyage of Thanksgiving" along the Pacific coast

of the North American continent. Höküle'a sailed south along the West

Coast, reaching thousands of Hawaiians who no longer lived in the

Islands, but longed to share in the canoe's legacy. Hawai'iloa sailed

north to thank the native peoples of Southeast Alaska for their gift

of trees for her hulls. This was an opportunity for the PVS to give

back to them, but at each stop the canoe and crew were overwhelmed

with gifts and kindness.

Soon after the ceremony, six canoes - Höküle'a, Hawai'iloa and Makali'i

from Hawai'i; Te Au o Tonga and Takitumu from Rarotonga; and Te Aurere

from Aotearoa - left the Marquesas Islands for Hawai'i, following

a traditional voyaging route. It was the first time in hundreds of

years that a fleet of Polynesian sailing canoes had journeyed together

- a new 'ohana (family) of the ocean star paths. Almost immediately

after arriving home in Hawai'i, Höküle'a and Hawai'iloa were shipped

to Seattle for a "Voyage of Thanksgiving" along the Pacific coast

of the North American continent. Höküle'a sailed south along the West

Coast, reaching thousands of Hawaiians who no longer lived in the

Islands, but longed to share in the canoe's legacy. Hawai'iloa sailed

north to thank the native peoples of Southeast Alaska for their gift

of trees for her hulls. This was an opportunity for the PVS to give

back to them, but at each stop the canoe and crew were overwhelmed

with gifts and kindness.  A

Quarter-Century of Achievement

A

Quarter-Century of Achievement