|

A

World of Natural Signs

By

Sam Low

Sailing Magazine

"Bring

her down!"

With this command from the navigator, my watchmates and I throw our

weight against the steering paddle to bring our vessel off the wind.

For days, we've been sailing through heavy swells frosted with whitecaps.

A chilled 25-knot wind blows over our bow. Rain slants across the decks.

We are aboard a sailing craft the likes of which have not been seen

for centuries. She is called Hokule'a - star of gladness - and she is

a replica of canoes that once carried Polynesian explorers to discover

and settle thousands of islands in a vast watery domain known as the

Polynesian Triangle. Since she was launched in 1975, Hokule'a has sailed

to all the corners of the triangle - except to the east which is anchored

by the tiny island of Rapa Nui (Europeans call it Easter Island) - our

destination.

To a modern sailor's eye, Hokule'a appears strange. She is sixty-two

feet long. Her twin hulls are joined by laminated wooden iako and fastened

by rope lashings woven into complex patterns reminiscent of the art

of M. C. Escher. The deck is lashed over the iakos to provide a place

for the crew to live during the day. The hulls rise up sharply at each

end and terminate in a graceful arc, called a manu, where wooden figures

with high foreheads and protruding eyes, the akua or guardian spirits,

stare out over an empty sea. Viewed from above, the canoe's strangeness

is dispelled. She looks like a catamaran.

Hokule'a's shape is ancient but her construction is not. A hundred years

ago, her sails would have been woven from Pandanus frond, but no one

knows how to do that today so they are made of Dacron. Her hulls are

fiberglassed marine plywood because the art of carving such canoes from

live wood has almost vanished along with the ancient canoe makers, the

kahuna kalai wa'a. Nainoa Thompson, the canoe's navigator, calls her

a "performance replica."

"We wanted to test the theory that such canoes could have carried Polynesian

navigators on long voyages of exploration throughout the Polynesian

triangle. We wanted to see how she sailed into the wind, off the wind,

how much cargo she could carry, how she stood up to storms. Could we

navigate her without instruments? Could we endure the rigors of long

voyages ourselves? Frankly, that was enough of a challenge. It didn't

matter if the canoe was made of modern materials as long as she performed

like an ancient vessel."

The Polynesian triangle is a huge chunk of real estate, larger than

all of Europe. Before her first voyage in 1975, academics and seafarers

were pretty much mystified by how the Polynesians settled such a vast

ocean. Thor Heyerdahl had a vision of sailors riding the prevailing

winds and currents from South America aboard balsa rafts - drifters,

not sophisticated seafarers. In 1948, he sailed Kon Tiki from Peru to

the Tuamotu Islands to settle the point. But he was wrong. Evidence

from archeological excavations, genetic research, linguistics and anthropology

has since proven that Polynesia was colonized from Southeast Asia by

sailors who voyaged against the wind and currents, explorers embarked

in craft much like Hokule'a.

It is September 29, the 8th day of our voyage. For the last week we

have lived in our heavy weather gear--working, eating and sleeping fully

tented in glossy yellow Patagonia slickers.

"This voyage will test you," Nainoa told us a few days before departing,

"it will test you physically, mentally and spiritually."

After our watch, we seek shelter in our "pukas" - a space about 6 feet

long and 3 feet wide under a sloping canvas roof which is only partially

watertight - it bleeds brackish droplets, a mixture of salt spray and

rainwater. Still carapaced in our foul weather gear, we slither into

our berths and try to sleep, grateful for the respite from the cold

wind and the cry of "bring her down!"

But one of us almost never goes below. Nainoa spends his time on deck

in all weather, mostly awake, always alert to the wind, stars and swells.

He catnaps in bad weather like this, a sprawled lump of yellow pants

and slicker, his hood pulled tight over his head, for maybe 15 minutes

at a time. The rest of us sleep at least 6 hours a day and often more,

yet we still are fatigued.

From our jumping off point in Mangareva we plan to sail east more than

1500 miles into the open Pacific. We will navigate as the ancients did

- without charts or instruments, we will use the stars, ocean swells

and flight of birds to guide the canoe. Our target is tiny, Rapa Nui

is only about 14 miles wide and 20 long. An error of only ½ a degree

in estimating latitude (an equivalent of 30 nautical miles) will cause

us to sail past the island. The next stop will be South America, 2000

miles away.

"The voyage to Rapa Nui will be the ultimate proof that our ancestors

were able to navigate successfully anywhere in their world," Nainoa

told us before we departed.

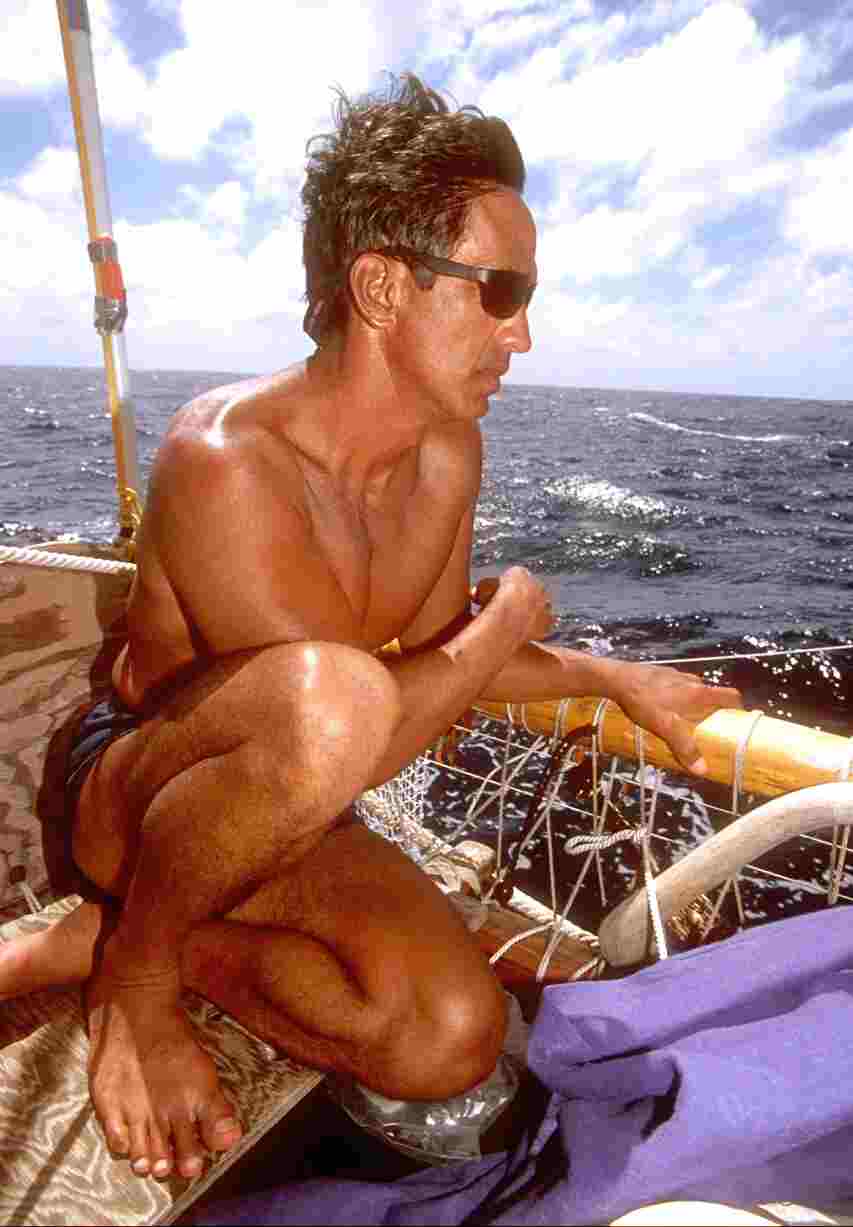

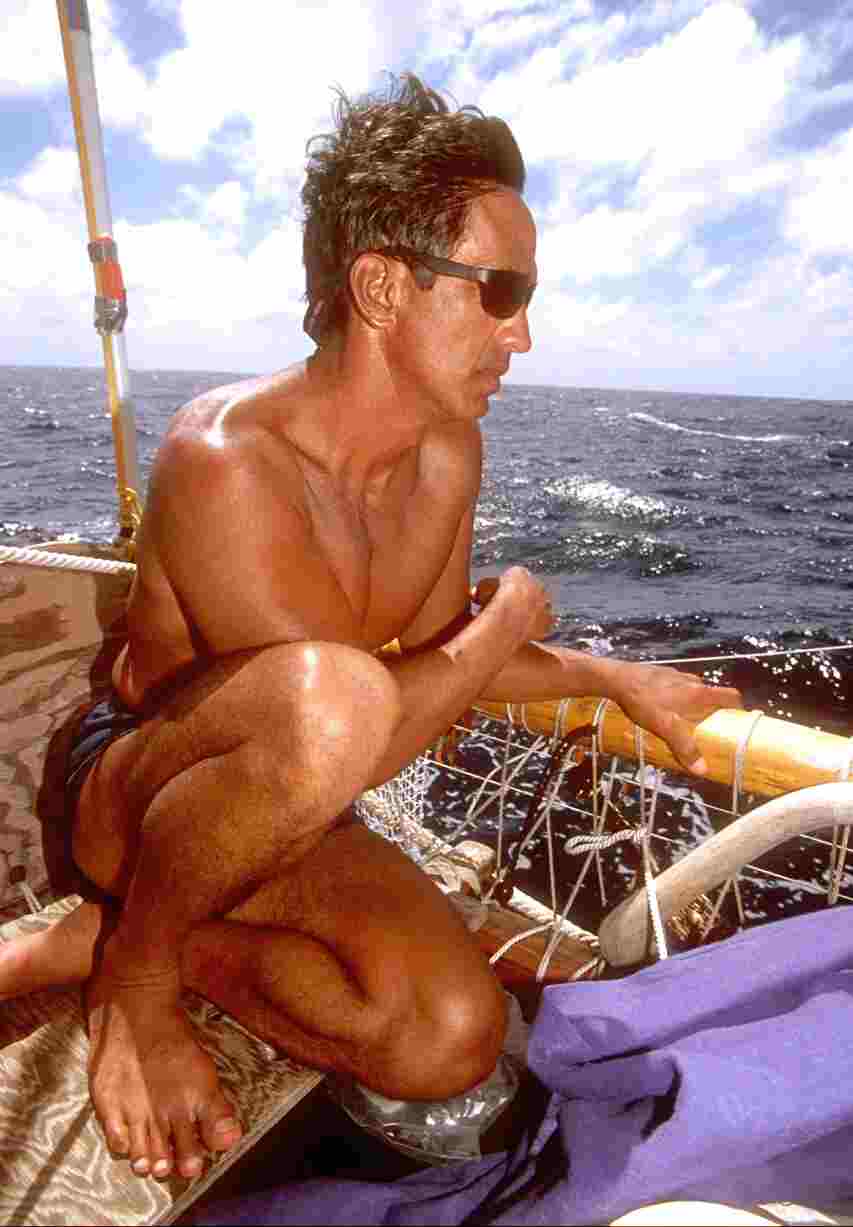

During the voyage Nainoa spends most of his time on the navigator's

platform aft, staring out to sea. I am careful not to interrupt his

concentration, waiting until his vision has refocused on something aboard

the canoe before talking to him (my job is to document the voyage in

words and photographs). I begin to see Nainoa willing himself back a

few thousand years to an era when Polynesian navigators sailed across

this same expanse of ocean.

"When everything is going right," Nainoa once explained to me. "I get

into a zone, a special place in which all of my relations with the canoe,

the natural world and the crew are integrated. You have to be in that

special place to navigate well. When you are in the zone, you feel ahead

of the game. You find yourself naturally thinking about what will happen

next and you are acting in the future, not reacting to things in the

past. You have the star patterns in mind and you seem to know where

you are even when the sky is cloudy and you can't see the stars. You

begin to anticipate the weather. It's an awesome feeling but it's hard

to describe. It is like being inside the navigation, participating from

the inside."

Nainoa's system of navigation is like all great discoveries - both complex

enough to render description difficult yet, at its foundation, incredibly

simple. It is based on years of observation, both of the real sky and

of an artificial one - in the planetarium of Hawaii's Bishop Museum.

It is also based on the teachings of Mau Piailug, one of the last Micronesian

Palu, navigators who find their way by a world of natural signs.

As a compass Nainoa uses the rising and setting points of stars. On

this voyage, for example, Sirius rises at 107 degrees and Aldebaran

rises at 70 degrees; while Vega sets at 317 degrees and Antares at 242

degrees. In the entire menu of Nainoa's directional stars there are

about 200. Swells also provide clues to steer by. Take the southwest

swell (Correct?) that has accompanied us for the entire voyage. Generated

by a hurricane off the coast of Australia, more than 5000 miles away,

it is satisfyingly deep and constant. We set our course by it at during

the day and at night when the sky is occluded, which is often.

The big trick, of course, is not just knowing where we're going but

where we are at any given moment. Determining Latitude, our position

north and south, is accomplished by judging the altitude of stars above

the horizon when they are at the meridian - the highest point in their

arc across the sky. Each star tells a different story because it arcs

differently, so the navigator has to memorize the path of dozens of

them. Judging altitude takes practice and the ability to use one's hand

as a crude instrument. Nainoa's little finger, when held at arms length

and adjusted to lie along the horizon, marks off 2 degrees of altitude.

Sighting along the crease between his hand and upthrust thumb gives

a reading of 13 degrees.

During Nainoa's study in the planetarium, he traveled across the ocean

in compressed time to observe patterns in the wheeling night sky. He

noticed certain pairs of stars rising and setting on the horizon simultaneously

- but only at one specific latitude - a phenomenon he calls "synchronous

rising and synchronous setting." When Murzim (near Sirius) and Alhena

(in Gemini), for example, drop below the western horizon at the same

time he knows the canoe is at six degrees south latitude. When Sirius

and Pollux set together he knows that his position is 17 degrees south.

Every day at sunrise and sunset, Nainoa gathers with two assistant navigators,

Chad Baybayan and Bruce Bruce Blankenfeld, to assess their progress

in the previous twelve hours. On the morning of October 1st at dawn,

the three men look out over an ocean stirred only by gentle undulating

swells and ruffled by tiny wind ripples.

"What an awesome night that was," says Nainoa, "I saw Jupiter rise on

the horizon, so the atmosphere was really clear. I was able to get a

good view of Atria in the south and Ruchbah in the north. The latitude

I got from Atria was 25 degrees S, and from Ruchbah I got 26 degrees

S. I think we ought to average the observations so let's say we are

at 25 degrees 30 minutes S."

Longitude cannot be found without a chronometer, so the navigators rely

on a system called, appropriately enough, "dead reckoning." They estimate

the time and speed they steer a given course and, on a mental map, they

place themselves along an imaginary course line toward their destination.

Last night, on the 6 to 10 p.m. watch, Hokule'a was beset with light

fickle winds.

"I don't think we made any progress during that watch," Nainoa says.

The canoe was stalled during the other watches as well. When the three

men add up their estimates of miles traveled during the night - factoring

in the effects of steering various courses as the fickle winds permitted

and leeway - they arrive at an estimate of only 6 miles of easting.

But this progress was impeded by a westerly current so the net distance

traveled east was only 3 miles. According to their calculations, the

distance to Rapa Nui is now 461 miles. In all of these calculations,

errors naturally accumulate.

"We can guess our distance traveled by dead reckoning, if we are very

careful, with maybe a 10% error, and we can guess our latitude with

an error of about one degree," Nainoa says.

I do the math in my head - 10% of 1500 miles (the distance along our

east- west course line toward Rapa Nui) is 150 miles. One degree of

latitude (along a north south line) is 60 miles. So that gives us a

box of accumulated error that is equivalent to nine thousand square

miles. Finding the tiny island in that vast space seems at best improbable

- but that's a personal opinion, which I keep to myself.

"One thing has always been certain," Nainoa says, "if we looked at this

voyage scientifically there is almost no chance of finding Rapa Nui.

If we thought that way, we would not have chosen to go. But you know

what? I bet we find it!"

During the evening of October 2nd, the sky presents millions of stars.

The wind is gentle, northerly. Jupiter rises ahead, almost due east.

I steer by aligning skymarks with various parts of the canoe - Jupiter

with the forestay, the Scorpion with the upthrust sternpost, Alpha Centauri

with a starboard shroud. As Jupiter rises from the sea it arcs north.

The angle its arc makes to the horizon matches both our latitude and

the tilt of Earth's axis, about 26 degrees. When Jupiter rises as high

as Hokule'a's mast it no longer serves as a trusty guide, but then Saturn

breaks the horizon and I line it up with one of the canoe's fore shrouds.

The ancient Hawaiians called the planets hoku 'ae'a - wandering stars

- because they appear to move through the otherwise permanent starfield.

Our ancestors probably employed the planets as we do, by using the stars

to determine their positions before we set our course by them.

During the next four days the winds are fickle, on and off from differing

directions. The sky clouds over. During the evening of October 6th and

the early morning of the 7th we continue toward Rapa Nui, tacking occasionally

to take advantage of wind shifts, hoping the sky may provide a glimpse

of our guiding stars. This does not happen. With only the swells to

provide direction, our navigators guide us to our rendezvous with an

invisible abstraction - the latitude of Rapa Nui - 27 degrees 9 minutes

S.

At 6 a.m. on October 7th, Bruce, Chad and Nainoa predict that we are

28 miles north of the latitude of Rapa Nui and 217 miles west of the

island. But we have sailed a zigzag course for the last few days, which

makes dead reckoning difficult. Under the best of conditions, error

accumulates - and, for the last few days the conditions have been far

from the best.

All that night and on into the morning the winds continue to blow strong

from the northeast and Hokule'a responds by speeding east-southeast

- 6 to 7 knots at times - slicing through the waves, producing long

tendrils of spray from her bow. Lookouts are posted. Near dawn, Max

Yarawamai spots two holes in the clouds ahead low on the horizon.

"I looked carefully at the two holes," Max explained later, "checking

first the one on the starboard side. I saw nothing there so I switched

to the hole on the port. I saw a hard flat surface there and I watched

it carefully. Was it an island? The shape didn't change! It was an island

all right." Nainoa's latitude estimation was dead on, and his dead reckoning

of longitude was accurate to within perhaps fifty miles. We had found

the dot in the ocean.

During that day we sail toward the island. Night descends. The lights

of Hanga Roa glisten on the eastern horizon. We ghost along the coast

of Rapa Nui until the watch change at ten PM when we tack toward the

island - a dark smudge on the horizon against a glittering curtain of

stars.

The 6-10 watch lingers on deck, enjoying the last few moments of comradeship

with each other and with our canoe. We watch Jupiter and Saturn rise

over the island to starboard and to port the Pleades and their guardian,

Taurus. We do not speak - our presence together on Hokule'a's heaving

deck expresses more deeply then words the bond that has been made in

the last seventeen days at sea.

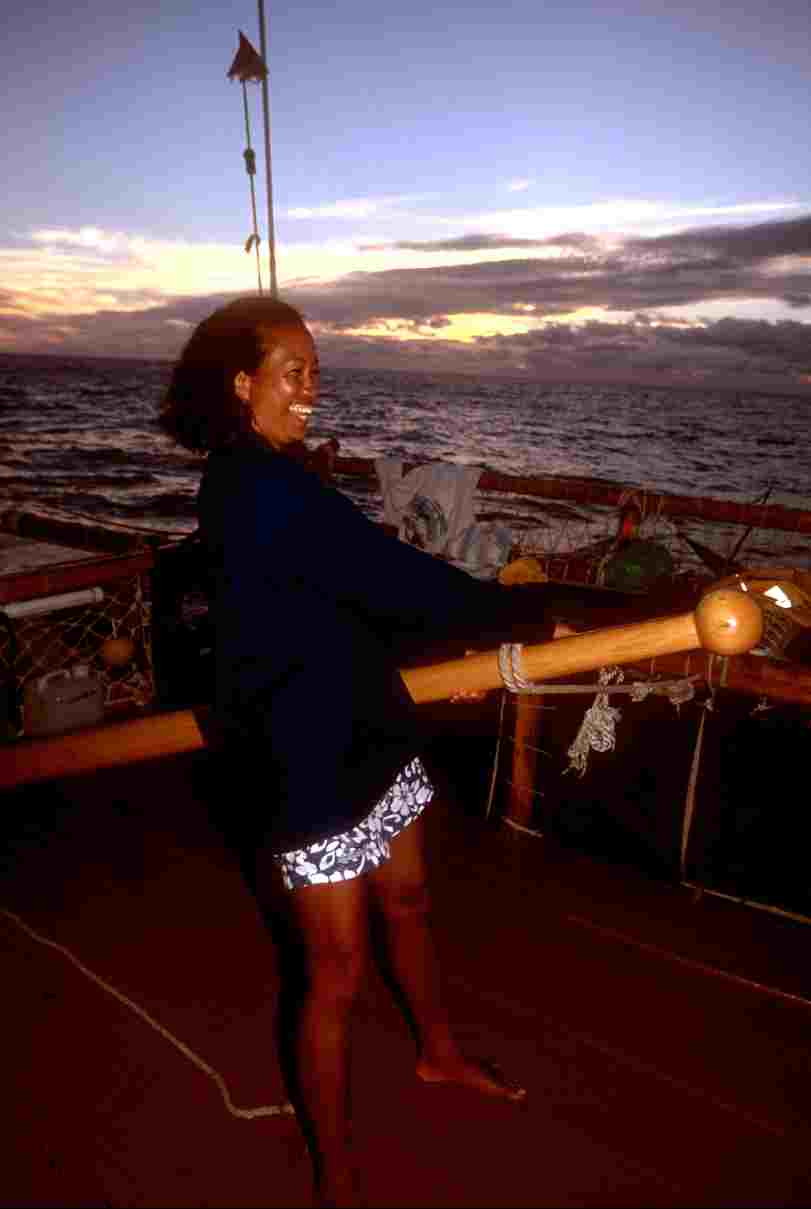

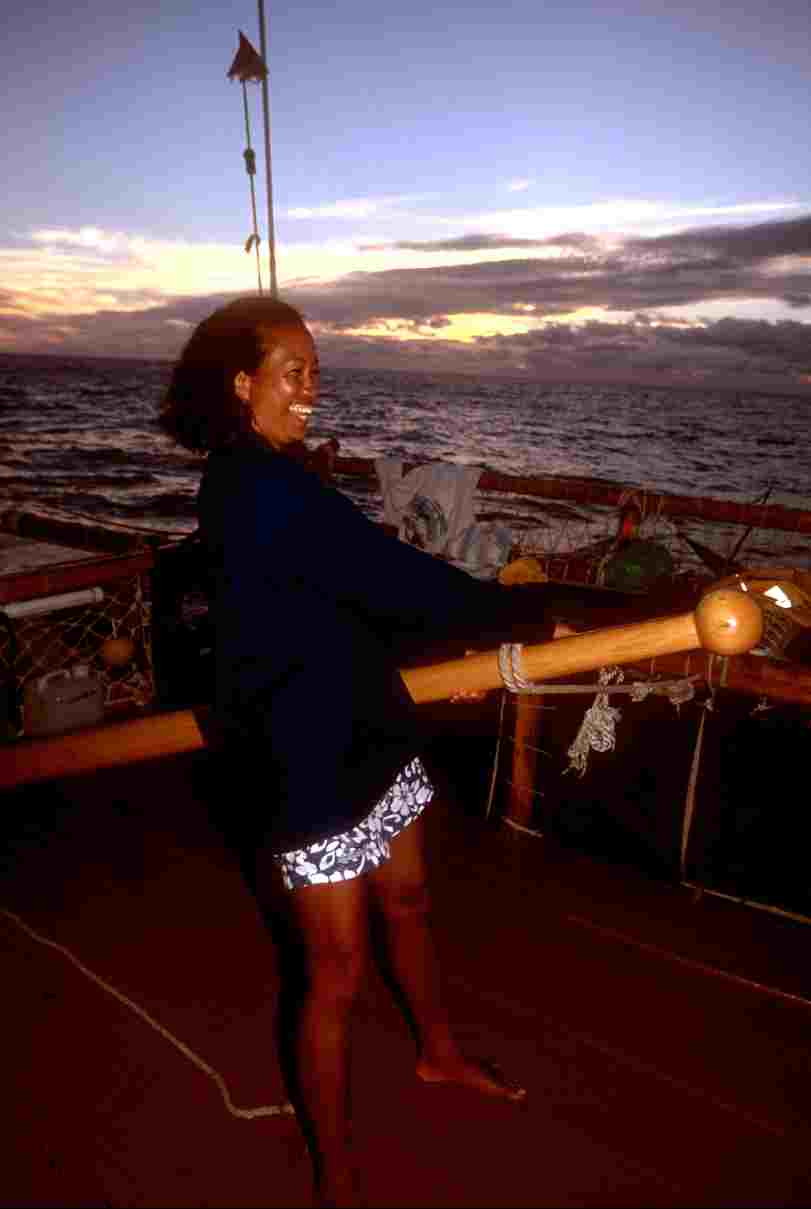

Reflecting back on the trip, I remember a serene and crystalline night

when Hokule'a slipped gracefully over gentle swells. The canoe's deck,

open to the skies, made it seem like I could reach up and touch the

Milky Way. Plankton glowed in our wake, turning the sea as effervescent

as champagne. Large globs of green light flared up, shimmered for an

instant, then slowly faded. We seemed to float through a universe of

jewels. I watched the helmsman bend over the canoe's massive steering

paddle. In silhouette against the sky he appeared engrossed in the performance

of an ancient ritual. Here, perhaps as far away from the influence of

modern life as one can get, time stood still. I imagined myself on the

deck of an ancient Polynesian canoe, making the first voyage to Rapa

Nui. The past lived.

|