|

'The

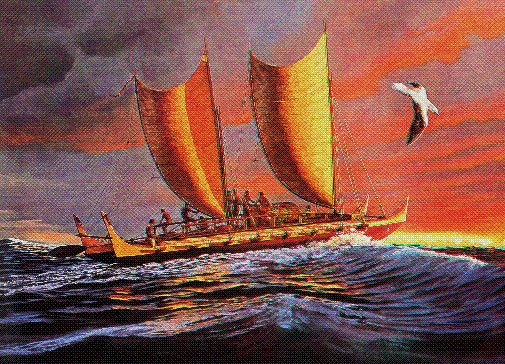

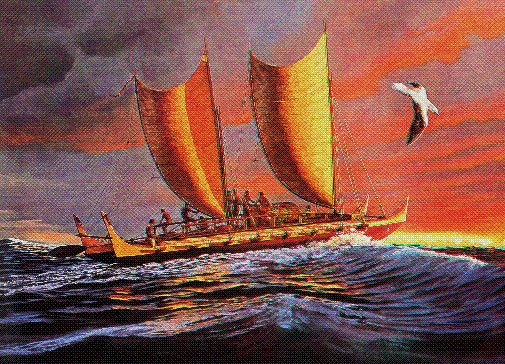

Spaceship of our Ancestors'-HOKULE'A

By

Sam Low

Wooden Boat Magazine

On the horizon's razor edge

at dawn, where a platinum ocean meets a brightening sky, I first saw the

sails-dark swaths filled by the northeast trade winds. Then four canoes

took shape, three big ocean voyaging ones-HOKULE'A (star of gladness),

MAKALI'I (eyes of the chief) and HAWAI'ILOA (named for a famous Hawaiian

chief)-and the small coastal canoe MO'OLELO, all reconstructions of boats

whose design dates back at least a millennium. It is March 12, 2000, and

I awaited their arrival at Kualoa on the island of Oahu, standing within

a charmed circle of men and women who had sailed these vessels, surrounded

by traditional priests in flowing robes garlanded with sweet smelling

maile leis.

Behind us stood dozens of hula troupes, singers and chanters, waiting

to perform traditional ceremonies of welcome that will continue into the

evening. Among those gathered in reverential silence are Polynesians from

Tonga, Samoa, the Cook Islands, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Aotearoa (New

Zealand), the Marquesas, Tahiti-from all the corners of the great Polynesian

Triangle, ten million square miles of ocean sprinkled with islands like

tiny stars. All these people had come to celebrate the 25th anniversary

of the construction of one of these canoes, HOKULE'A, an event that has

inspired a far-reaching cultural revival.

In 1973, Hawaiian artist Herb Kane, anthropologist Ben Finney, and boatman

Tommy Holmes formed the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PS) to experiment

with the theory, supported by extensive scientific research, that Polynesians

had peopled the vast Pacific by long voyages intended for colonization

and exploration. Their first project was to build HOKULE'A-a reconstruction

of an ancient voyaging canoe-and sail it on a 5,000-mile round-trip between

Hawaii and Tahiti. Ancient canoes were fashioned from hollowed-out logs

caulked with breadfruit sap and fastened with coconut-fiber lashings,

but the knowledge of building such vessels-and the materials to build

them-had long since been lost in Hawaii. So they built a "performance

replica," accurate in outward appearance and function, but fabricated

from modern materials, in this case plywood sheathed in fiberglass.

Herb Kane - painting of Hokule'a

When HOKULE'A was launched at Kualoa on March 8, 1975, Nainoa Thompson-then

a 21-year-old Hawaiian crew member-attended the ceremonies. "It was the

first time," he remembers, "that I had heard an ancient chant in my own

language or seen a classic-style hula. My grandmother grew up in a time

when Hawaiians were beaten in school if they spoke Hawaiian and they were

ashamed to be dark-skinned. Ever since the arrival of Capt. Cook [in 1778],

we have been increasingly disconnected from who we are. But when I watched

HOKULE'A slip into the sea, it kindled in me something that I only partially

understood but felt instinctively-pride in my heritage."

The canoe rapidly proved her mettle in sea trials, but one key element

for the voyage to Tahiti was still missing-a navigator to guide her without

instruments or charts. Such knowledge existed only among a handful of

men called palu who still sailed outrigger canoes among the islands of

Micronesia, finding their way by natural clues to direction-the arc of

stars, the flight of birds, and the curl of ocean swells. So from the

tiny island of Satawal (a sister island to Puluwat) came Mau Piailug.

He would navigate HOKULE'A on her first voyage. Nainoa flew to Tahiti

to sail on the return trip, and he remembers HOKULE'A's arrival vividly.

"Seventeen thousand people came down, over half the population of the

island. It was a spontaneous reaction by a people who had maintained their

language and their genealogy, who understood who their great navigators

were. They knew about the great canoes, but they didn't have such a canoe.

So when HOKULE'A entered the bay, she was a powerful symbol that reminded

them of the greatness of their culture and their heritage-and therefore

themselves."

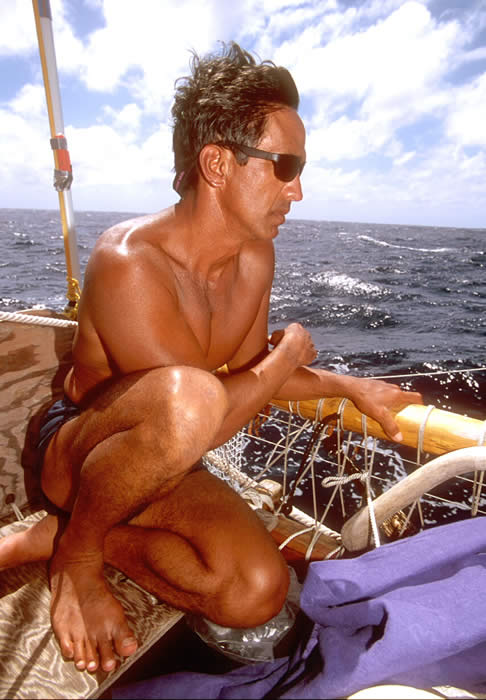

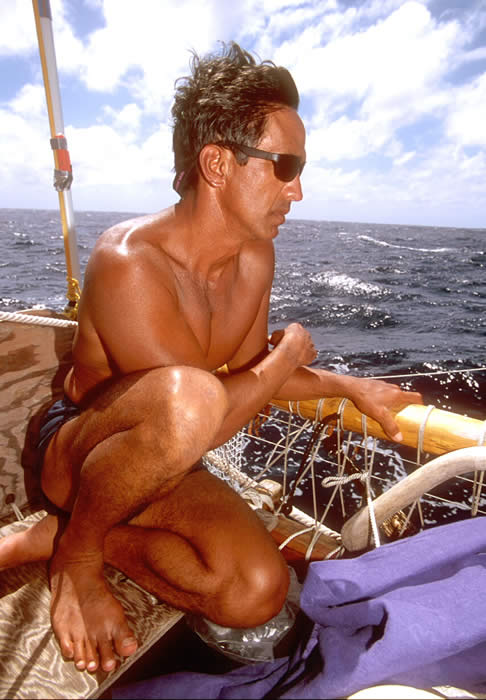

Nainoa Thompson

After returning to Hawaii aboard HOKULE'A, Nainoa found it difficult to

return to normal life. "The whole sailing experience was so powerful that

getting off the canoe left a huge void," he remembers, "I had to continue."

Working with his father, Myron "Pinkie" Thompson, who had been named president

of PVS, Nainoa planned another trip to Tahiti. In 1978, Mau Piailug returned

to Hawaii to teach him the secrets of navigation. "Mau trained us like

his grandfather had trained him," Nainoa says, "he took us on the sea

like children, becoming our father and mother on the ocean. We had very

few formal lessons: the learning really came by being close to him-looking

at the things he looks at, feeling the things he feels." After two years

of rigorous training, Mau proclaimed his young Hawaiian student ready

to navigate by himself.

In 1980, Nainoa became the first Hawaiian to navigate the ancient sea

route to Tahiti in perhaps a thousand years. This success added fuel to

a growing Hawaiian cultural revival that by then included dance, chant,

medical practices, architecture, and religion. "HOKULE'A was the spaceship

of our ancestors," as one Hawaiian put it, "she was the highest achievement

of our technology. She kindled our pride. And she taught us that as a

people we could do anything we set our minds to."

What Nainoa and others set their minds to in the following 20 years of

voyaging was nothing less than stitching together all the islands of Polynesia.

In 1985, HOKULE'A sailed to the Society Islands, the Cooks, New Zealand,

Tonga, Samoa, and back to Hawaii via Aitutaki, Tahiti, and Rangiroa in

the Tuamotu Archipelago. In 1992, she voyaged to the Pacific Arts Festival

in Rarotonga. And in 1995, she returned to Tahiti to join a fleet of Polynesian

sail for an epic voyage to Hawaii via the Marquesas called Na 'Ohana Holo

Moana-the Voyaging Family of the Vast Ocean. The family now included six

seagoing canoes in addition to HOKULE'A-from Tahiti came TAHITINUI, from

the Cook Islands came TAKITUMU and TE AU TONGA, from New Zealand came

TE AURERE, and from Hawaii two new canoes-MAKALI'I and HAWAI'ILOA.

"We call HOKULE'A the 'mother canoe,' " says TE AURERE's Maori captain,

Hector Busby, who had come to Kualoa to attend the canoe's 25th anniversary.

"She inspired us all to achieve something no one considered possible-building

a canoe of our own to rediscover our ancestral heritage as a seafaring

people, and through that the rediscovery of ourselves."

By 1995, HOKULE'A had sailed more than 75,000 nautical miles and had visited

all the frontiers of the Polynesian triangle except one-the easternmost-which

is occupied by a single island, Rapa Nui. In HOKULE'A's 1999 voyage to

"close the triangle," I served among Nainoa's crew.

As I stood in the throng awaiting the canoes' arrival at Kualoa almost

a year after that voyage concluded, my mind flashed back to days of cold,

stinging winds, and nights of crystalline beauty filled with planets as

bright as tiny moons and the swirling Magellenic Clouds. A burst of sound

from a dozen conch shells broke my reverie. HOKULE'A had touched ashore

at Kualoa. The welcoming ceremonies had begun. "Famous are the voyages

of HOKULE'A in the long seas, in the short seas, in the choppy seas of

Kanaloa, O Kanaloa, e Kanaloa of the long seas," proclaimed one of the

chanters in impeccable Hawaiian, reverently intoning the blessing of Kanaloa,

the Hawaiian god of the sea. Hula troupes garlanded with leis performed

dances that had not been seen for many generations. In song, oratory,

chant, and dance, Polynesians from the far frontier of the triangle demonstrated

what HOKULE'A had accomplished in her 25 years of voyaging-the full expression

of a renewed culture.

|