Sam Low

Just another WordPress site

CREW PROFILE Pomaikalani Bertelmann

CREW PROFILE

Pomaikalani Bertelmann

2007 – Voyage to Satawal

By Sam Low

A generation or so ago two Bertelmann brothers married two Lindsey sisters and the trajectory of history in the Big Island town of Waimea shifted slightly. Glenn Bertelmann and Delsa Lindsey had seven children and Clay Bertelmann and Deedee Lindsey produced five – a tight family with deep roots in a much larger `ohana that thrived beneath the gentle catenary arc of Mauna Kea. In Clay and Deedee’s family, Pomaikalani was the first-born – on March 7, 1973, in Honoka`a. At the time, her father was a well known Parker Ranch cowboy, so it’s not surprising that young Pomai grew to love horses – in fact, animals of all kinds.

“I was basically raised on my family’s ranch and riding was a passion since I can remember,” Pomai says. “I also worked as a kid on Hale Kea ranch in Waimea, fixing fences, raking the arenas, exercising horses and taking care of the livestock.”

Waimea was less dressy in those days, an informal rural town where children could safely ride horses along the main street and in the surrounding empty pastures. They rode to the Dairy Queen drive-up window to order hamburgers, they staged informal barrel and baton races and played “musical chairs” in the vast empty prairie just outside town.

“A sense of community was second nature among us,” Pomai says, “there were kids from all the families – the Keakealani family, also Rebozos, De Silvas, Kimuras, Lindseys – a lot of Lindseys – Kainoas, Colemans, Kanihos, Kaauas, Bergins, Awaas, Purdeys and the Fergerstrom family – to name a few. All of us were kaukalio (riding horses).”

One of the biggest events in Waimea was the fourth of July rodeo organized by the Parker Ranch Roundup Club where cowboys from the ranch’s numerous divisions competed in various events – cutting, roping, racing.

“The cowboy life style was not exclusive of women, not at all. There were a lot of awesome women riders too. Lorraine Urbic sat a horse like no one else, and she won a lot of races. Then, just to name a few, there was Hoppy Whitehead, Val Hanohano, and Peewee Lindsey – all of them very strong people – great role models for us.”

But life in Waimea embraced more than the land-based culture of the Paniolo.

“One of my fondest memories,” Pomai explains, “was loading up the family Bronco with my mom and dad and the five of us kids and then picking up all my cousins and food and camping gear and heading for the beach. We went to a place called Wailea at Puako. There was no one there in those days. We had the place all to ourselves. Right next to where we used to camp there’s a telephone pole with the number “69” printed on it. Since then, things have changed. Malahini now call Wailea “number sixty-nine”. When you lose the real Hawaiian name, you lose a lot.”

At Wailea and other places, Pomai learned to dive with her father and she enjoyed fishing but never really grew fond of other water sports. As a youngster it was always the life kaukalio and with animals that attracted her most. But in 1975, her Uncle Shorty sailed aboard Hokule`a on her maiden voyage to Tahiti.

“We supported him as a family, and whenever the canoe came to the Big Island we helped care for her and her crew.”

During the series of voyages between 1985 and 1987, Pomai’s father Clay sailed often aboard Hokule`a.

“He was away at sea for maybe six months during those two years, and I began to wonder a little about the kind of life he was leading.”

Gradually, Pomai’s family was becoming more and more entwined with the sea. From 1989 to 1991 the Bertelmann family helped search the forests surrounding Mauna Kea for koa logs to build Hawai`iloa. They cooked and packed food for the searchers, walked side by side with them during long weekend treks – took a key role in the entire process. Ultimately, so devastated were Hawai`i’s forests, that no logs were found and the canoe was built instead of Alaskan spruce. But from this effort, Mauloa was born – the first traditionally made Hawaiian six man coastal canoe fashioned within perhaps centuries.

“We did find Koa logs big enough for a smaller canoe,” Pomai explains. “We went to Keahou to fell the trees and we lived there over a long weekend in tents.”

The canoe builders used adzes that they fashioned from stone gathered at the ancient Keanakakao`i adze quarry on Mauna Kea under the watchful eye of Mau Piailug. From 1991 to 1993, Pomai’s father Clay spent every weekend at Pu`uhonua O Honaunau working on the canoe.

“In traditional times women were not allowed to work on canoes so we supported the men,” Pomai explains. “Mauloa was built by the Na kalai wa`a – the canoe builders – from Koa and Breadfruit sap and sennit and Lauhala, her hulls were smoothed by stones and she was given a sheen with Kukui oil.

In 1992, Pomai went with her father to O`ahu to help him prepare for Hokule`a’s voyage to the Cook Islands. There she met a group of young people who were beginning to assume leadership roles – Moana Doi, Keahi Omai, Ka`au McKenney and Chad Paishon, who she would eventually marry.

“I began to think seriously about my life in 1992,” she remembers, “and as I learned more about the values involved in voyaging, I thought I wanted them in my own life. Voyaging gave me a sense of family – which was familiar since I had grown up in a strong supportive family – and it gave me a connection to my cultural roots. And when Mau Piailug began to stay with us I met a man who had done so much for our people – how could I not be excited?”

Next came Makali`i – the Big Island canoe built by a passionate community effort spearheaded by Clay, Shorty and Tiger Espere. Beginning work in January 1994, the canoe was finished the following December. In September, Pomai became – as she puts it – “a one woman administrative staff,” for Na Kalai Wa`a Moku O Hawai`i – The Canoe Builders of Hawai`i. She was hooked.

In 1995, Pomai sailed aboard Makali`i from Tahiti, through the Marquesas, and back to Hawai`i. “Then in 1997, Mau asked us to take him home to Satawal on Makali`i and, of course, there was no question about it.” In February of 1999, Makali`i raised anchor and set out on the voyage called E Mau – “Sailing the Master Home.”

“We sailed to many islands in Micronesia to honor Mau among his own people,” says Pomai. “On Satawal I saw Mau as a complete man for the first time – not just as a navigator – but also as a father, a husband, a fisherman, a farmer – you should see his taro patch. I have never seen him so happy.”

Soon after Makali`i returned from Micronesia, Pomai was once again deeply immersed in organizing the details of caring for the canoe and organizing it’s many educational voyages. Through the intimate grapevine of Hawaiian sailors, she learned of Hokule`a’s upcoming voyage to Rapa Nui. “I also heard that it might be Nainoa’s last voyage as a navigator,” she remembers, “and I was heart broken. I always wanted to sail with him. I thought I might never get the chance.” A short time later, Nainoa called and invited her to come aboard Hokule`a for the fifth leg – the voyage home.

“This is such an honor for me,” Pomai says, “to have a chance to not only learn from Nainoa but from the greatest sailors of the last quarter century of traditional voyaging – from Uncle Snake and Uncle Mike and Uncle Tava. I’m now sailing with the guys who started the renewal of our ancient voyaging arts and contributed to the beginning of the revival of our Hawaiian culture.”

Crew Profile – Abraham “Snake” Ah Hee

CREW PROFILE

Abraham “Snake” Ah Hee

2000 Voyage – Hawaii to Tahiti

by Sam Low

“My father taught me to get lobster without a spear,” Snake Ah Hee explains, “you have to be gentle, have a good hand, or you spoil the hole. If you do it right you can come back in a few days and there will be another lobster there.”

Snake was born on March 18, 1946 in Lahaina, Maui. He lived for a time with his great grandfather in a house on the ocean outside town. “It was a fishing family. “We had nets and canoes and ever since I was a small kid my dad took me fishing. I learned the different areas to fish, how to find the fish, how the current moves, how to steer a canoe using Japanese oars.” Snake’s father, Abraham Ah Hee, Sr., was called “Froggy” because he swam so powerfully and could stay underwater so long. Like most Hawaiians, Snake began to surf as a youngster, gradually becoming comfortable in big waves. He surfed for a time with the Wind and Sea Surf Club, a California group, and in contests he often went home with a cup marked “first place.” Later he was on the Gregg Knoll surf team and paddled for the Lahaina Canoe Club where he was also a coach. “I still love to surf,” Snake says, ” and I hope to do it into my eighties. The ocean has taken hold of me spiritually and mentally. I think it’s because it’s tied in with my family, with being raised on the ocean.”

Snake graduated from Lahainaluna High School in 1964 and worked as a life guard at hotels on Maui. He joined the National Guard and was called up in 1968 to go on active duty – one tour in Vietnam. He served in the Southern war zone, not too far from Saigon, and he rose to be a squad leader in charge of patrols.

“It made my mind stronger,” he says, “more adult. It taught me the value of life. It’s crazy to fight. I hope my children will never go to war. I want to see peace – all the time – all over the world.”

Snake has five children, three girls and two boys: Malia Mahealani, Nainoa Chad, Makalea Rose, Mau Nukuhiva, and David. It’s not an accident that the names Nainoa, Chad and Mau appear in this family. “Hokule`a brought all her crew together, “Snake says, “we’re like a family of brothers and sisters. I can go anywhere in Hawaii and stay with my `ohana. On the Big Island, for example, I stay with Shorty or Tava or Chad; on Moloka`i maybe with Mel Paoa or Penny Rawlins. I might not see them for a year but when I do it seems like just a short time.”

In 1975, Snake first heard about Hokule`a and that she would sail to Tahiti, but he had never laid eyes on her. “Then one day I was in my truck on the way to the canoe beach and I saw this boat coming from Lana`i. ‘What’s that?’ I thought. I stopped. I had never seen anything like it before.”

Later, George Paoa and Sam Ka`ai came to the beach where Snake was life guarding and asked him to be a member of the crew. He began training right away and was chosen for the return trip from Tahiti to Hawai`i. That’s where he first met Nainoa.

“That trip gave me a real good feeling inside,” Snake remembers, “It was a good thing for my generation. The canoe makes us strong in mind and spirit – close to our culture. If not for the canoe I won’t say that our culture would be lost, but it would be weaker. It helped bring back the language, and helped bring back the community, not only in Hawai`i but throughout all the Pacific – wherever she has stopped.”

“On this trip,” he continues, “I’m here to teach the younger generation who are sailing with us – how to take care of themselves and each other – how to be humble. For me that’s the one key part. If you’re humble everything will be fine. Everyone will think the same, work the same, be closer together. Only if you are humble can you learn.”

Vision – Myron “Pinky” Thompson

Vision

Myron “Pinky” Thompson

Myron Pinky Thompson provided a core vision that we have carried on our canoes for the last thirty years. In essence, it is simple; in application, it is deep and complex. As president of PVS, Pinky’s vision united past, present and future by reaffirming that traditional Polynesian values applied universally across time and space.

“Before our ancestors set out to find a new island,” he explained, “they had to have a vision of that island over the horizon. They made a plan for achieving that vision. They prepared themselves physically and mentally and were willing to experiment, to try new things. They took risks. And on the voyage they bound each other with aloha so they could together overcome the risks and achieve their vision. You find these same values throughout the world, seeking, planning, experimenting, taking risks and the importance caring for each other.”

“The same principles that we used in the past,” he often said, “are the ones that we use today and that we will use into the future. No matter what culture we are, or what race, these are values that work for us all.”

Lau Lima – a laying on of hands

Lau Lima

A Laying on of Hands

By Sam Low

Sailing Hokule’a with a crew of volunteers over routes not traversed for perhaps a millennium has presented many crises. One such occurred in May of 1997, when Nainoa hired a surveyor to inspect the canoe prior to its voyage to Rapa Nui.

A marine surveyor is empowered to say whether or not a vessel is seaworthy. He uses simple tools, a trained eye, a pocketknife and a rubber mallet. With his knife he probes for dry rot, a kind of virus that reduces wood to dust, although not obviously so to the naked eye. Poking in strategic places tells the story. If the knife goes in easily, the wood is rotten. Banging on the hull with a mallet may produce discordant notes to a surveyor’s ear, another sign of problems.

After a few hours of poking and banging on that May afternoon, the surveyor made his report: “the canoe is rotten,” he said. “I cannot certify her seaworthiness. I suggest you think about putting her in a museum.” The pronouncement was a surprise but not a shock. Nainoa had seen places where there was dry rot, but the canoe had taken him safely across many oceans and had demonstrated more than seaworthiness, she had shown her mana, her strength of spirit. Retiring Hokule’a to a museum was not an option.

“I need two lists,” Nainoa said to the surveyor, “I need a list of what’s wrong with her, and a list of what to do to make her even stronger than when she was built.”

The what-to-do list was long. Two of the wooden iakos had to be replaced – an onerous job but not exceedingly so. The hull was another matter. Wooden stringers run lengthwise from bow to stern, providing strength. There are five such stringers on each side, many of them rotten. The job of fixing all these problems fell to Bruce Blankenfeld.

In September, the canoe went into dry-dock. Perhaps “dry-dock” is a misnomer because it conjures a picture of Hokule’a in a mammoth shipyard cofferdam. Hokule’a’s dry-dock was a shed in a decrepit section of the Port of Honolulu. Nearby was a junkyard with a tall fence and barking dogs, a pile of sand for making cement, a small marina, a few boatyards that did not appear very busy. Bruce set about finding workers.

“It’s easy to find people when you’re ready to go sailing but when you need them to maintain the canoe it can be pretty difficult. I had a group of young folk come down at the beginning of September and tell me they wanted to help. I said, ‘well, it’s pretty easy to do that. All you have to do is show up.’ But after they saw all the work that was going on, they never returned.”

What the prospective workers saw was nasty. Young men and women squirmed through hatches only slightly wider than their shoulders where they toiled for hours, in Stygian gloom, amidst fiberglass dust and the odor of polyvinyl resin. They excised the rotten stringers. They fitted new sections of wood. Then they “sister-framed” each stringer by adding two new pieces of wood, one on top and one on the bottom. Triangular wedges of foamed plastic followed for yet more strength and to “fair” the stringers into the hull. They sanded all this smooth and laid layers of glass fiber over it. They pushed resin into the fiber’s mesh. When it hardened, the process was repeated. Then again. Three coats of resin; then two coats of paint. Meanwhile, other volunteers sanded off the hulls’ gel-coat. Fiberglass dust veiled the canoe, clogging the pores of exposed skin. For eight months, Bruce found himself down at dry-dock at odd hours inspecting the work. Seeing his crew laboring over the canoe was like seeing a resurrection.

“Even though the work was hard, there was always a lot of energy. We saw progress every day. People are working together in the same place. It’s usually dry and, compared to sailing the canoe, working conditions are luxurious. There are fits and starts, but everything seems to come together all right in the end. You are working on something that is very beautiful. You are touching the past with sandpaper and saws and rope lashings.”

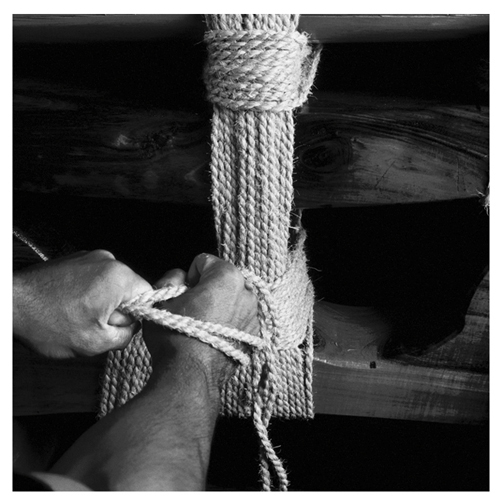

Bruce supervised his crew as they stripped the canoe’s twin masts and brushed on eight coats of varnish and sanded each to the texture of baby-skin. Then they renewed five miles of rope lashings a few feet at a time. They ripped off deck planking, replaced and relashed it. The canoe received new iakos, new splashboards, and new manus fore and aft. She received stanchions, catwalks, hatches, and wiring for running lights and emergency radios.

An army of volunteers donated thousands of man and woman hours to Hokule’a’s rebirth, a laying on of hands that expressed their deep commitment to the canoe and what she meant to them. They came from all walks of life. There is Russell Amimoto, for example, nineteen years old, a professional house painter and volunteer canoe lasher. He has served Hokule’a for three years. There is Kamaki Worthington, twenty-six, a teacher, fiberglasser, also a veteran of three years service. There is Kiki Hugo, in his forties, a cross country trucker who spends long months on the mainland driving from San Francisco to the Bronx, the Bronx to San Francisco, until he earns enough money to return home to Oahu. He is a kupuna, an elder crewmember with twenty-five years service. There is Lilikala Kamalehiva, fortyish, college professor, chair of the department of Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawaii, Hokule’a’s chanter and master of protocol; Wally Froiseth, early seventies, once Hawaii’s most famous big-wave surfer, now captain of the pilot boat of the Port of Honolulu; Jerry Ongies, early sixties, retired Army officer, ex-manager Dole Pineapple plant, boat builder, cabinet maker, canoe fabricator. This list of workers is an extremely small selection of the hundreds who donated their time to the canoe. The complete list would fill a book. If you were to ask these people why they have so freely given of themselves to the canoe they will provide a variety of reasons, unique to each of them, but there will also be a common response similar to what Nainoa once told an audience of legislators when they asked him why they should fund Hokule’a and her voyages.

“We must sail in the wake of our ancestors,” he told them, “to find ourselves.”

Finally, on the last week in March, the work was finished. The surveyor returned with his knife, his mallet and his well trained eye and certified the canoe “Lloyds A-1,” nomenclature used by the world’s largest insurer of watercraft to signify complete readiness for sea. A few days later, the canoe was launched. Among the men and women who tended Hokule’a as a giant crane lifted her from her cradle and laid her upon the ocean was Bruce Blankenfeld.

“The mana in this canoe comes from all the people who have sailed aboard Hokule’a and cared for her,” Bruce said, looking out over the crowd that had come down for the launching. “I think of the literally hundreds of people who have come down and given to the canoe when she was in dry dock. I think of everyone who has shared similar work since she was first launched in 1975, those who have sailed aboard her, the men and women in all the islands we have visited who hosted us. All of this malama – this laying on of hands – adds to the mana of the canoe. It is intangible but it is alive and well.”

The Doldrums and Na’au – Nainoa Thompson

The Doldrums and Na’au

March 15, 1980

by Sam Low

Monte Costa photograph

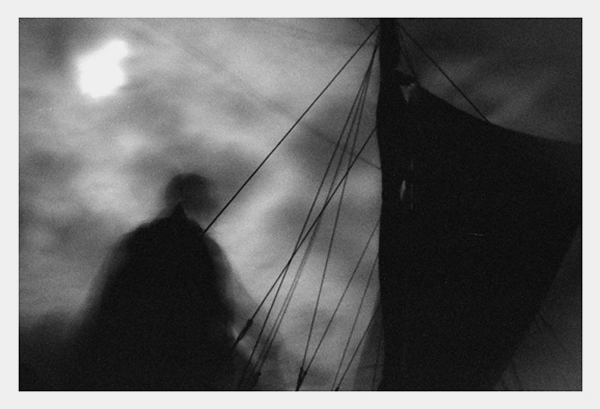

Thirty years ago, Nainoa set out on his first voyage as navigator.

In 1980, after training for three years with Will Kyselka and Mau Piailug, Nainoa boarded Hokule’a as the first Hawaiian navigator in centuries to set out for Tahiti. In spite of all his preparation, he struggled with deep anxieties about the voyage. He felt responsible for the safety of his crew. He felt the weight of constant public scrutiny – of television cameras and news interviews. Mau had lived with the sea and the stars all his life, how could he expect to emulate even a part of his genius? And in the midst of a renaissance of pride among Polynesians, his success – or failure – took on new dimensions.

“I was afraid every day that I was in Hilo waiting to go. I constantly rehearsed everything that could go wrong – instead of focusing on how to make it work. I felt responsible for the crew’s safety and also for the whole public arena, for doing well.”

“The day we finally left the Hilo breakwater stands out powerfully in my mind, because all of a sudden I felt much better. Now I focused on making the journey, not worrying about it. But I was still worried about staying awake. Mau never sleeps at sea. He can stay up all night, for weeks on end. I thought, “how in the world am I going to do that?” Not sleeping was part of Mau’s magic, not part of mine.”

“Mau told me that the mind doesn’t need much rest, but the physical body does. So when the navigator is on the canoe, the crew does the physical work. ‘When you are tired,’ he said, ‘you close your eyes.’ He told me that even though his eyes were closed, he is always awake in his heart. And when I sailed with him, I saw that was true. Preparing for the voyage, I tried to figure out how Mau stayed awake. I forced myself to stay up for a day or so but then I collapsed. I couldn’t do it. So when we left Hilo I felt like I was voyaging both into an unknown ocean and into unknown regions of my own potential.”

“It was ten thirty at night. Tumor was rising, Maui’s fishhook. I thought, “it’s pretty late and I had better get some rest or I will be a basket case tomorrow.”

“I lay down and closed my eyes. I thought, ‘how stupid you are. You are not prepared to go to sleep. You cannot sleep.’ So I got up and from then on I slept only two to three hours a day. When I became so exhausted that I couldn’t think, I lay down. I slept until I dreamed. Then I got up. I slept maybe ten or fifteen minutes at a time and that was enough. My mind was refreshed. I learned to do that for a month. It was a whole new reality.”

As the voyage progressed and Hokule’a neared the equator, Nainoa worried about what would happen when the canoe entered the doldrums where hot air ascends from a three hundred mile wide belt of ocean. Here the constant northeast trades winds die off to be replaced by long periods of calm, followed by severe buffeting squalls, then windless days once more. It’s a navigator’s nightmare. Which way is the current taking me? How fast? From what direction did the wind blow in that last squall? In what direction did it push us? How far? Where am I?

“I dreaded the doldrums. I had no confidence that I could get through it. I thought that I could only accurately navigate if I had visual celestial clues, and that when I got into the doldrums there would be a hundred percent cloud cover. I would be blind. And that’s what happened. When we arrived n the doldrums, the sky went black. It was solid rain. The wind was strong – about 25 knots – and it was switching around. We were moving fast. That’s the worst thing that can happen – you are going fast and you don’t know where you’re going. I couldn’t tell the steersmen where to steer. I was very, very tense. I knew that I had to avoid fatigue – I couldn’t allow myself to get physically tense. But I couldn’t help it. I just couldn’t stop myself.”

“I was so exhausted that I backed up against the rail to rest. Then something strange happened. When I gave up fighting to find a clue in the sky and I settled down, then, all of a sudden, a warmth came over me. All of a sudden, I knew where the moon was. But I couldn’t see the moon – it was so black.”

“The feeling of warmth and the image of the moon gave me a strong sense of confidence. I knew where to go. I directed the canoe on a new course and then – just for a moment – there was a hole in the clouds and the light of the moon shone through – just where I expected it to be. I can’t explain it, but that was one of the most precious moments in all my sailing experience. I realized there was a deep connection between something in my abilities and my senses that goes beyond the analytical, beyond seeing with my eyes. It was something very deep inside. And now I seek out those experiences. I can’t always do it. I have to be in the right frame of mind. I can’t conjure up those experiences consciously. But they are coming more often now. It just happens. I don’t want to analyze it too much. I just want to make it happen more often.”

“Before that happened, I tended to rely totally on math and science because it was so much easier to explain things that way. I didn’t know how to trust my instincts. My instincts were not trained enough to be trusted. Now I know that there are certain levels of navigation that are realms of the spirit. Hawaiians call it na’au – knowing through your instincts, your feelings, rather than your mind, your intellect.

Taking Hold of the Old Story – Sam Ka’ai

Taking Hold of the Old Story

Sam Ka’ai

By Sam Low

Sam Ka’ai was brought up in Kaupo, an old district of Hawaiian homesteads in rural East Maui. Until 1938, there was no road to Kaupo. When they finally put one in, Sam’s father and stepfather worked on it. His family raised pigs and cattle. They fished. They grew papaya, avocado and peanuts. They made okolehao, liquor distilled from ti root. “We grew our own food,” Sam remembers, “so we didn’t know there was a depression going on. We had little need for money. We made our own pipes for smoking. A pipe bought in a store was called ‘a lazy man’s pipe.’” Sam’s father and grandfather made canoes. Sam continued in this tradition, although as a carver of fine sculpture. He used adzes that came down to him from his ancestors. They were fashioned a century or so ago.

Herb Kane traveled to each island to introduce the concept of the voyage, taking the Hawaiian pulse at each encounter. In 1973, Sam Ka’ai went to Maui Community College to listen to Herb talk about Hokule’a. When the talk was over, Sam stood up holding a copy of Honolulu Magazine and pointed to a picture of the canoe. He spoke to Herb in Hawaiian. Herb said “speak English please.”

“We cannot participate in the making of your canoe because it’s going to be in Oahu, so maybe we can make some small part,” Sam said. “In the picture, there are two ki’is (sculpted figures) on the two manus – the two stern pieces of your canoe. Have they been made yet? If not, I will do it.”

It was a busy meeting so Sam gave Herb his address and left. A few days later, a letter arrived from Herb: “if you come from a canoe family, please dream and make your own design for the ki’is.”

Sam carved two ki’is – a man and a woman. The female figure would be lashed to the port manu, the male ki’i to the starboard. When Sam carved the male figure he fashioned his hands reaching up to the heavens in supplication.

“This is an effigy of how we are after so many years of oppression,” Sam explains. “Blind to our past, we reach up to grasp heaven one more time. The same stars are rising at the same time as they did for our fathers for many, many generations. So if you lose your way – if you cannot find your way – remember that you once sailed on your mother’s lap and you were never lost. The stars turned minute by minute, hour by hour, dawn and dusk and you always came home or your kind wouldn’t be here. So you were never lost. This is an effigy of the Hokule’a experience – the ohana wa’a, the family of the canoe. He is reaching above himself, beyond himself, to the story that has not changed, the forever and ever story, the olelo, olelo, olelo – down the corridor of time – the lei of bones. He is showing that we are taking hold of the old story once again.”

Finding My Way – Nainoa Thompson

Finding My Way

Nainoa Thompson

by Sam Liow

Becoming a Crew Member for the First Voyage to Tahiti

It was the first year I was paddling for the Hui Nalu Canoe Club, and I happened to be at the right place at the right time. Herb Kane was living across the canal from the club at Maunalua Bay. It was 1974, and Herb, Tommy Holmes, and Ben Finney were designing Hokule’a. The canoe hadn’t been built yet, but they had a smaller canoe then, and they’d ask us to paddle it out of the canal over the reef into the open ocean. That was great! I was at the club every day so I could paddle the canoe out.

Then one day, Herb invited two of the paddling coaches and me over to his house. Herb’s house was filled with paintings and pictures of canoes, nautical charts, star charts, and books everywhere, interesting books! Over dinner Herb told us how they were going to build a canoe and sail it 2,500 miles without instruments-the old way. “We’re going to follow the stars, and the canoe is going to be called after that star,” Herb said, pointing to the star Hokule’a (Arcturus). This voyage would help to show that the Polynesians came here by sailing and navigating their canoes-not just happening to drift here on ocean currents or driven by winds. The voyage would do something very important for the Hawaiian people and for the rest of the world.

In that moment, all the parts connected in me that had seemed unconnected in my life. I was twenty and looking for something challenging and meaningful to do with my life. I had a hard time finding that inside the four walls of a classroom. Here it was-the history, the heritage, the stars, the ocean, and the dream… there was so much relevance in that dream. I wanted to follow Herb; I wanted to be part of that dream.

Herb told us what the requirements would be to sail to Tahiti. We would have to go through a training program in which we would learn all about the canoe and how to sail her, and there would be physical training and training in teamwork. They would select the best 30 from the several hundred who participated in training.

When Hokule’a was completed in the spring of 1975, I participated in the training and was assigned to the return crew. If I want to do something, I can be very disciplined. My dream was coming true.

Back Cove Log

Published in Soundings Magazine

August, 2005

as “Maine Sailor Tried his Hand with Power”

(What were they thinking?)

Article and Photos by Sam Low

by Sam Low

Anchored at Jewell Island

I have to admit my prejudice right away.I like sailboats. Under wind power I have cruised many thousands of miles in contentment – along Maine ‘s foggy coast and among dazzling Polynesian islands. I love the commitment to nature’s rhythms that sailing requires. So I was apprehensive when I took the assignment of cruising favorite downeast grounds in a power boat, but the week my wife and I spent aboard the twenty-nine foot Back Cove surprised us. We came away with some prejudices intact, but discovered that powering offers advantages that cannot be ignored.

_______________

On wednesday, at DeMillo’s Marina in Portland , we need four wheelbarrows to carry our gear – and two more trips lugging our kayaks.

“Holy mackerel,” says Jon Spaulding, Back Cove’s CEO, “this boat is an overnighter and it looks like you’re making a transatlantic crossing.”

Not exactly, but I did plan to use the Back Cove’s speed to range widely. We will power beyond familiar Penobscot Bay waters to cruise further downeast. Machiasport, a 400 mile round trip, is our ultimate destination.

We depart in thick haze, apprehensive about narrow passages between islands and busy harbor traffic. We needn’t have worried, the ship’s GPS plotter – centrally located in front of the helm – shows the way to Jewell Island in Casco Bay .

“What kind of boat is that? She’s a beauty!” comes the call from a sloop as we maneuver to anchor.

“She’s a Back Cove 29,” I answer, “a new design by a company in Rockland .”

“Well,” says my neighbor bestowing high praise,”she looks like the kind of power boat a sailor would like.”

The Back Cove’s sheer is a svelte curve punctuated by a trim cabin that sweeps back to a graceful pilot house with windows all around providing excellent visibility. Her fittings – bow pulpit, rails, cleats, portholes – are of the quality lavished on the best sailing yachts. Below decks, she presents warm cherry joinery to accent the cabin’s sleek fiberglass curves. A table pops up between the vee berths for dining and descends to provide a spacious sleeping platform. The galley is to one side – topped by Corian – the head and shower to the other.

As tenders we’ve brought two small Lincoln kayaks. On this first evening, we glide on still waters listening to gulls’ cries. Seals pop up to examine us with an experienced gaze. Then they lift their snouts and slip backwards into the deep.

On Thursday morning , a nearby fog horn moans. A sailboat departs only to return out of the gloom an hour later, her captain having decided to lay over until it clears. It’s deceptively peaceful but weather reports say it won’t last long. Hurricanes Bonnie and Charlie are racing north from the Gulf of Mexico .

The fog lifts enough in the afternoon to see distant islands. I plan to go to Robinhood Cove, about thirty miles away, and hole up there. In a sailboat, such a trip would mean six hours of windward slogging but in little more than an hour we’re off the Sheepscot River . The waves are four feet and cresting but the Back Cove moves along at 20 knots with negligible effort. Lured by this promise of speed, we pass Robinhood by and head for Round Pond in Muscongus Bay . Taking a mooring for the evening, we paddle ashore to the Anchor Inn – one of our favorite Maine restaurants.

Pemaquid Point

Round Pond is aptly named – an almost perfect circle of water rimmed by modest year-round cottages and the occasional newcomers’ splendid summer home. NOAA weather predicts heavy downpours and fog as Bonnie sweeps across Maine , followed by Charlie. Here in the sheltered harbor it’s peaceful. We think of moving on, but by ten AM the fog creeps upriver, clinging to the cool water. Houses ashore drift from view. The lobster fleet is moored up – slickers hung in cockpits.

“That fog looks pretty thick,” says Karin.

We decide that if the locals won’t go out, either will we. But how will it be to hole up on a 29 foot power boat designed for day trips? We’re about to find out.

I first sailed downeast more than 30 years ago on a 28 foot Eldridge-McGinnis sloop, single handing among fir clad islands for months at a time. I cannot help comparing her to the Back Cove.

Breakfast in the pilot house

Below decks, the sloop enveloped me like a spacious cave. The Back Cove, on the other hand, divides her length like a split level ranch into the cabin and pilot house. At first, I miss the sloop’s comfy main saloon but that changed when we zipped shut the canvas to enclose the pilot house. Karin reads there while I sprawl below on the ample berth – the stereo low – a cup of coffee at hand.

“The only thing I miss is my dog and my fireplace,” Karin says.

The Back Cove is not designed for extended cruising and we’ve brought way too much stuff – but we find places to stow it all. The pilot house has many cubbies, there’s ample space in the lazarette and shelves accumulate the normal cruising clutter. Under the bunks go our duffel bags.

Our cruising range has shrunk with these two lost days. Machiasport is now out of range. The weather forecasts a window of clearing tomorrow so if we’re lucky we’ll get to Criehaven – our planned first day destination – on day three.

On Saturday , after Bonnie’s passage, the skies clear to present pine studded islands and sailboats moving sedately across the glistening Medomak River . Offshore, Bonnie lingers in the form of eight foot swells, sending spray over the pilot house and giving us a lumpy ride. Yet we maintain 20 knots, making Criehaven by two PM .

Criehaven

Criehaven is a time warp to an era before the bustle of yachts and visitors. It’s one of Maine ‘s outermost islands, a fishing village in the truest sense. Lobster gear is piled high on piers. There’s no running water. No electricity. Generators and a few communal wells provide these necessities.

Karin and I walk through the tiny village and across fields lined with wild rose and loostrife, encountering Wyeth houses under Wyeth skies. We enter a Hobbit’s forest by a rutted road ponded with Bonnie’s rain, following a sign that says “Bull’s Cove.” The earth underfoot is springy – the consistency of peat – carpeted with moss and lichen and ferns. A heron hoots in the distance. We follow the sound of surf to the cove and look out at a thickening layer of mackerel clouds descending to the sea.

“Here comes Charlie,” we think – and we turn back to the boat.

All day, NOAA has predicted winds from the southwest but now they decide we’ll get 30 knots from the northeast – right down the throat of Criehaven’s tiny harbor. A clear advantage of a powerboat is the ability to scamper for cover when the weather deteriorates, so we slip our mooring and beat it at 25 knots to sheltered Rockland harbor.

On Sunday morning, we learn that Charlie has taken an unexpected turn off shore. NOAA predicts light winds and clearing skies so I plot a course to traverse Penobscot Bay to Little Cranberry Island and a favorite shore front restaurant – The Isleford Dock.

“We’ll dine out in the style to which we’d like to be accustomed,” I announce to Karin, who – from the look of it – is none too pleased with the prospect of yet another 25 knot dash.

The trip takes us through Fox Island thoroughfare and Merchant’s Row. The seas are slate colored and oily under a monotone sky – as if Bonnie had sucked all the energy with her as she passed out to sea.

Cruising on a powerboat, I discover, is an intellectual exercise rather than a sensual one. The pilot house isolates us from wind and spray. The engine’s beat overwhelms the subtle sound of fog horns and bell buoys. My gaze flicks constantly between the sea ahead and the GPS plotter as Karin barks out landmarks from the chart. Like flying an aircraft at low altitude – the Back Cove requires constant attention.

We duck into Burnt Coat Harbor on Swan’s Island , thread the narrow channel to the east and head toward Little Cranberry. At 25 knots, I swerve through a minefield of lobster buoys. In this part of Maine , the lobstermen use a main buoy and a smaller one, called a toggle, attached to it by a light line. If you pass between the two buoys you’ll foul the prop.

“So far, so good,” I think – just as I pass over a toggle line. I cut the throttle and hold my breath. No luck. The lobster buoy trails behind, twisted around our prop.

A cold wind blows. The ocean is black beneath our keel as I struggle to unwind the lobster warp. “I really don’t want to dive into that dark sea,” I think. Luckily, I am able to untangle the mess, cut the line and tie it off so the fisherman won’t lose any gear. We resume our journey, now chilled to the bone.

Just off Great Cranberry Island , we overhaul a classic picnic boat sedately cruising at eight knots – a relic with a plumb bow, graceful shear and an upright pilot house. Her passengers sit on folding chairs, chatting quietly. We rush by at three times her speed, shivering and ready for a warm seat at the Isleford Dock bar.

Dinner is splendid – eggplant in Sezuan sauce, tuna tartar, calamari, Angus steak, fried onions and asparagus, washed down with a flinty Pinot Grigio.

On Monday, the Isleford lobstermen are up at five loading bait at the Co-op.

Isleford Fisherman’s Co-op

“Fishing is good,” one lobsterman tells me, “but it would be nice if this rain would stop.”

I agree. This is our fifth day on the boat and only one has been clear and sunny.

Little Cranberry is quiet. We walk past trim cottages with dayglow lobster buoys in the door yards and summer bungalows cosseted by gaudy flowerbeds. A few folks drift past on whirring golf carts. Wood smoke perfumes the island with the scent of fall.

Back on the boat, we see Mount Desert humped against the horizon like a stranded whale. The sky is mottled steel, the ocean flat and unsullied. Sailboats motor past under bare poles. We decide to sightsee. We spend the day visiting Bass Harbor and Mackerel Cove – then motor on to a dinner engagement with friends at Isle au Haut .

Paradoxically, the possibility of speed induces lassitude. Unlike cruising under sail, there’s no need to get under weigh at eight – or nine – to make a distant landfall. So we don’t. On Tuesday morning, we enjoy the ritual of preparing breakfast and dining in our pilot house with a view. Then an exploratory paddle with our kayaks, writing in our journals and reading. After a hot shower we’re off to Matinicus, our last stop before heading home.

Matinicus Fish Shack

On Wednesday, the sun rises over Matinicus harbor behind a pink scrim of fog. The ring of a bell buoy joins the cry of gulls and the cough of diesel engines in an early morning chorus.

At low tide, fishermen’s shacks stand tall on barnacled stilts. This is our last day – an eighty mile dash to Portland awaits us as we sip our morning coffee and chat with folks moored close aboard.

We make the run into a headwind and choppy seas. We cruise at 22 knots, throttling back to 17 when the seas pile up in front of us. This is not fun. The roar of the engine and glint of ocean takes it toll. When we enter the channel to Portland Harbor , we’re tired and ready for lunch at DeMillo’s.

_________

So what’s the verdict? I have to admit that I missed the sensual process of voyaging under sail – attuning myself to changing wind and current, the breeze on my face, the acute awareness of sound all around – whooshing wake, bell buoys, moaning fog horns. But sailing takes up most of the daylight hours. Arrival at day’s end is a time for mooring and furling sails, a glass of wine and watching yet another stunning sunset. Many sailors set out early in the morning, needing time to make another destination. The Back Cove allowed us to make tracks from one anchorage to another with plenty of time for long walks ashore or seaborne probes in our kayaks. She encouraged reconnaissance – poking into anchorages we had never visited, moving quickly to yet another – bumblebees sampling nectar from many wide spread gardens.

Kayaking at Matinicus

We also discovered the joy of poking along at seven knots like picnic boats of yore, our engine a gentle hum, the fir studded islands gliding by, a cup of tea near at hand. The unexpected thing about speed was the ability to choose when – and where – to go slowly.

As a sailor, my first impression of the Back Cove was that she’s reckless with time, compressing distance in a way that was hard to get used to. But eventually she became just another boat. Not a sailboat. Not a powerboat. Just a boat.

It happened at Isle au Haut after a party ashore with friends. There was no wind. The sea was perfectly still. A gentle rain had settled over the harbor – the drops like chimes as they struck the flat seam of ocean.

This is what it’s all about, I thought. A time away from land and its cares – moments in which the sound of rain joining the sea is all there is. When we finally discarded our prejudices, the Back Cove – like all good boats – lulled us into a place circumscribed by islands and the healing rhythms of nature.